Editor’s note: Coastal Review regularly features the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the state’s coast. More of his work can be found on his personal website.

One day I hope that I will know more about Betty Town, a free African American community that white raiders destroyed just before the Civil War to make way for the founding of Aurora.

Supporter Spotlight

Now and then, when I have had time, I have done a fair bit of historical research on the people of Betty Town, how their land was taken, and how the community’s people were driven out of their homes.

But there is still much that I do not know. Many of the historical sources are opaque, some of them are difficult to understand, and none tell us what happened from the point of view of the people who lived in Betty Town.

I wish that I had to time to work through those difficulties. But the truth is, my life has somehow gotten far busier than I ever thought it would be at this age: I fear that I will never find the time to do justice to Betty Town’s history.

For that reason, I want to share here what I know now about Betty Town. That way, if other people are interested, maybe they will pick up where I have left off and go further.

Perhaps, after reading this, a younger scholar or a precocious student will take it on, or maybe even a descendant of those who lost their land and homes.

Supporter Spotlight

For me the voices of the people of Betty Town are like the fading sounds of whispers in the night. I catch a few words here, and a few words there, but it is always better if more people are listening.

Together we can share what we hear and maybe, just maybe, the story of Betty Town will not be lost.

‘Where the bear, free negro and wild cat roamed’

So I will go first. Here is what I know about Betty Town, the free African American community that used to be on the North Carolina coast, only 30 miles from where I grew up:

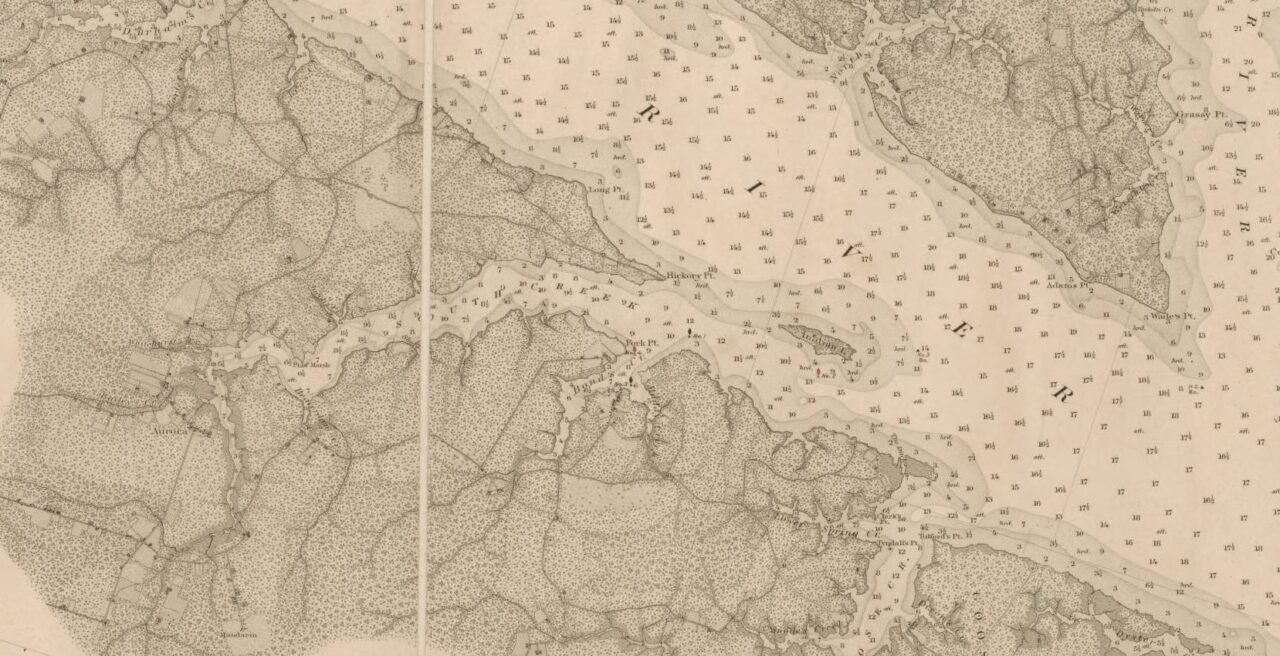

First, Betty Town was a rural settlement of free African Americans located on South Creek, 22 miles southeast of the town of Washington, in Beaufort County.

The community was a remote refuge from the evils of the day. Writing in the Feb. 4, 1886, Goldsboro Messenger, one former visitor remembered Betty Town as a land “where the bear, free negro and wild cat roamed at their own free will.”

Another white commentator, also writing after the Civil War, gives us a hint that at least some whites saw Betty Town’s independence and self-reliance as somewhat menacing.

Published in Raleigh’s Weekly Observer on Aug. 10, 1877, that writer declared that Betty Town and its vicinity had been a shady place up until 1857 or 1858.

That part of Beaufort County, the writer declared, was “regarded as an almost worthless swamp except for shingles and staves; the ridges being inhabited for the most part by a thriftless set of free negroes and half-breed Indians.”

That is the way that the state’s white leaders, at least many of them, used to talk about the communities of free, mixed-race people that were located in many different parts of North Carolina’s coastal plain.

In general, they were people set apart and who guarded their freedom, since they knew all too well that it could be taken away if they were not watchful. Nearly all lived off the land — farming, fishing, working in the woods.

The site of Betty Town is now the location of Aurora, a small town that, as the saying goes, has seen better days.

Betty Town’s 18th-century origins

The origin of Betty Town dates at least to the late 18th century and to a free African American couple named Isaiah and Betty Hodge. (Betty Hodge was the community’s namesake.)

The first U.S. census was taken in 1790. At that time, the Hodge family was already residing on South Creek.

In that first federal census of 1790, a “Zear” Hodge, Isaiah or possibly Isaiah’s father, is listed as the head of a household that included four people of color and a white woman.

At that time, Isaiah Hodge would have been 15 years old. He was born in or about 1775.

The Hodges’ neighbors included a sizeable cluster of other free people of color. They included families with the last names of Blango, Johnston, Holmes and Keys, among others.

Exactly how long that group of free African Americans had been in that part of Beaufort County is not clear to me.

However, I did consult the work of master genealogist Paul Heinigg, one of the leading authorities on the history of free African Americans in Virginia and North Carolina.

Heinigg’s research indicates that several free Black families left southeastern Virginia and settled in what became Betty Town and neighboring parts of southeastern Beaufort County earlier in the 1700s.

They included Blangos, Driggers, Perkinses, Moores, and Johnsons (or Johnstons), at the very least.

A free African American named Thomas Blango, for example, had settled in Beaufort County by 1701, and Blango family genealogists still trace the family’s roots in the county specifically to Betty Town.

Family Blango

According to Stanton Allen’s “Family Blango: A Study of Black American Genealogy,” three free African Americans families with the surname Blango resided at Betty Town in the early 1800s: those of John Blango, John Blango, Jr., and Mrs. Peggy Blango.

Stanton Allen’s article appeared in Bayboro-based The Pamlico News on Aug. 24, 1983.

By the 1810 census, Isaiah Hodge is listed as head of the Hodge household. Eleven others resided with him: 10 free Blacks and one individual who was enslaved, though apparently not by the Hodges.

Thirty years later, Isaiah Hodges is listed in the federal census as head of a household with 15 members, all free, and presumably including children and perhaps grandchildren, and maybe others, too.

(Census takers did not begin to enumerate individual names, other than heads of households, until 1850.)

By 1850, the last census before his death, Isaiah Hodge, then age 75, was listed as the head of a household that included his wife Elizabeth (Betty), three younger adults with the surname Hodge, and an enslaved mother and her five children.

Judging from the census, nine other households of free African Americans lived around them, presumably in what was considered “Betty Town.” They included families with the surnames of Tyson, Hagins, Perkins, Driggers, and maybe Simpsons.

(Judging by their listing in the census, the Simpsons may have resided in a nearby, but slightly different neighborhood).

When I reviewed the Beaufort County deeds at the State Archives, I failed to get a clear picture of Betty Town’s boundaries.

However, the deeds did indicate that Isaiah Hodge alone owned at least 300 acres on both sides of South Creek in the early part of the 19th century.

Betty Town’s boundaries may have been confined to the Hodge family’s holdings. Or the Hodge lands may have been only the heart of a larger territory that local people called Betty Town.

If Betty Town was confined to the Hodge family holdings, I would suspect that other families also resided on their land and that most of them would have been at least distantly related to Isaiah and Betty Hodge.

Figuring out those relationships will require more genealogical research, but one thing is clear: On the eve of the Civil War, Betty Town was a small but significant enclave of free African Americans that had survived in that part of Beaufort County since the 18th century.

The Free African Americans of South Creek

The free African Americans who lived in Betty Town were not alone. They were among a sizable minority of free African Americans who resided in that part of Beaufort County.

In the South Creek census district as a whole, free African Americans made up more than a quarter of the total free population in 1850.

According to the census, the South Creek district had a total population of 1,092 persons in 1850. That included 209 free Blacks, 294 enslaved people of color, and 589 free whites.

However, even if Betty Town and similar communities were refuges in some ways, that did not mean that they were safe.

The decade of the 1850s, as the people of Betty Town discovered, was an especially dangerous time to be a free African American in Beaufort County or anywhere on the North Carolina coast.

‘A Free Negro Named Isaiah Hodge’

According to census records, local deeds, and newspaper accounts, Betty Town had vanished by the beginning of the Civil War.

All historical sources that I have seen agree on the basic facts of what happened to Betty Town. First, they agree that one of Beaufort County’s wealthiest and most influential white political leaders claimed to have forcibly taken legal possession of the community’s land sometime in 1857 or 1858.

Even in white circles, it seems to have been acknowledged that the taking of Betty Town’s land was accomplished by legal chicanery.

Second, at least a significant part of Betty Town’s residents, including the Hodge family, refused to abandon their homes.

Third, the holdouts were eventually driven out of Betty Town not by lawful authorities, but by vigilantes.

That much seems clear. Many details do not seem clear to me at all, however. The historical accounts are relatively few, they clash in some cases, and large gaps in the story remain.

While I did not necessarily expect to find it, I was also disappointed not to find an account of Betty Town’s last days that was written by any of those who were dispossessed or their descendants.

To me that is an almost crippling omission. In my long years as a historian, I have repeatedly seen how contemporary white and Black views of historical events are often completely different. Again and again, I have found them to be as different as night and day.

All that said, even the surviving white accounts paint a sordid portrait of the destruction of Betty Town.

The most widely known account was written in 1916 by Robert Tripp Bonner, who was one of the most active local historians and genealogists in Beaufort County in the early 20th century.

A surveyor by trade, R.T. Bonner (1854-1919), who was white, came from Bonnerton, only a few miles from Betty Town, and spent much of his life in Aurora.

At the time of Betty Town’s troubles, he was just a young boy, five or six years old. However, he inevitably grew up hearing stories about Betty Town.

Years later, in 1880, when the town of Aurora was officially incorporated at the former site of Betty Town, he was the surveyor who laid out the town’s streets.

In the early 20th century, Bonner occasionally wrote articles on Beaufort County’s history in the local newspapers. One of those articles focused on the town of Aurora’s history.

Published in the Washington Progress in 1916, Bonner’s article was not hesitant about looking at Aurora’s origins:

“The land previous to the Civil War was owned by a free negro named Isaiah Hodge who died from the effects of a cancer and during his sickness was furnished with the necessities of life by Isaiah Respess who took a mortgage on the lands.”

Isaiah Respess was a prosperous merchant, farmer, and lumberman who had extensive land holdings across a broad swath of eastern North Carolina. He was also the mayor of Washington during the early part of the Civil War.

Bonner recalled that, after Isaiah Hodge’s death, which was apparently in 1857 or 1858, Respess called in the family’s debts and, when his widow Betty could not meet them, had their land confiscated.

He then “sold the land under execution by Sheriff Henry Alderson Ellison and bid it in about 1859.”

Sometime soon after, according to Bonner, “Rev. W. H. Cunningham, of Lenoir County, came to South Creek, bought the site of Aurora from Isaiah Respess and began the town.”

The Rev. W. H. Cunningham (ca. 1824-1895) was a Methodist minister originally from Greene County. Before coming to Beaufort County, he had been serving as the principal of Lenoir Academy, a private school in Kinston, the seat of Lenoir County.

He had a highly entrepreneurial spirit and was involved in a number of real estate and business ventures before, during, and after the Civil War.

The Dispossessed

The Hodges and their neighbors obviously believed that the taking of their land was an injustice.

By all accounts, they did not accept the legality of the sheriff’s proceedings, the right of Respess to have their land confiscated, or Rev. Cunningham’s right to evict them. According to Bonner’s story, they defied Rev. Cunningham and the county sheriff and refused to leave their homes in Betty Town.

Bonner continued:

“Mr. Cunningham had much trouble dispossessing the free negroes, but one Sunday night, [when] these negroes left their homes to go to a big preaching, Cunningham tore down their houses and took possession of their lands.”

The county sheriff evidently allowed the assault, but that would not have surprised anyone, Black or white, at the time. In antebellum North Carolina, free African Americans were left to defend their own.

Betty Town is unlikely to have survived so long if the community had not previously shown that it was able to defend itself.

In his history of Aurora, Bonner then says:

“These negroes emigrated to Ohio and as the law at that time forbid free negroes after leaving the state to return, they and their descendants did not come back.”

The Legal Status of Free African Americans

In 1830, North Carolina legislators prohibited free African Americans from returning to the state if they left for 90 days.

That law was part of a raft of laws and state constitutional amendments in the 1830s that deprived free blacks of many of the most basic rights of American citizenship.

Other rights taken away from North Carolina’s free African Americans in the 1830s included the right of free assembly, the right of free speech, the right to vote, the right to bear arms, and the right to testify against white citizens in court.

Without those rights, Betty Town’s citizens realistically had no path to defending themselves against the takeover of their land, at least not in court, even in the unlikely event that they could have found a local attorney willing to represent them.

According to Bonner’s 1916 story, after taking Betty Town’s homes and farms, the Rev. Cunningham renamed the place “Aurora.”

Even before the Civil War, he began recruiting new settlers to the former site of Betty Town by running advertisements in newspapers in other parts of North Carolina that made “Aurora” sound like Eden.

From North Carolina to Ohio

Betty Town’s refugees were not the only free African Americans who looked to the state of Ohio for shelter in those last years before the Civil War.

Confronted with severe restrictions on their legal rights and by growing white violence, an important number of North Carolina’s free African Americans found new homes in the northern states.

In the 1850s, Cleveland, Oberlin, and other parts of Ohio were especially common destinations for free African Americans from Eastern North Carolina.

Probably the best known of the region’s free Black exiles in Ohio was Lewis Sheridan Leary.

Leary left his family’s home in Fayetteville, and moved to Oberlin, Ohio, in 1856. He was active in the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society, probably active in the Underground Railroad, and was one of three Blacks who rode with John Brown at Harpers Ferry.

‘A Gang of Lawless Ruffians’

Another account of Betty Town’s last days was published just a short time after the community’s destruction.

Appearing in the North Carolina Times, a Raleigh newspaper, on Jan. 25, 1860, an anonymous letter writer calling himself “John Veritas” declared that he had visited “Aurora” that winter, while visiting friends in that part of Beaufort County.

In his letter, John Veritas indicated that he had read a newspaper advertisement placed by Rev. Cunningham that sought to recruit settlers to his new town. While in the area, he had decided that he wanted to see “Aurora” for himself.

To say the least, he had not been impressed. Rev. Cunningham’s advertisement apparently promised a bustling little town that already had churches, shops, a physician’s office, elegant homes, and other “fine edifices.”

Instead, John Veritas wrote, he found that his white friends there still called the area “Betty Town” and barely remembered hearing anything about a town called “Aurora.”

All that he found there, he said, was “one dwelling house, a schoolhouse, the ruins of an old house, [and] pine and gum saplings.”

Along one side of the schoolhouse, he reported, someone had scribbled a bit of graffiti.

BETTY TOWN, if you are so soon done for—

I wonder what you was ever begun for?

I could be wrong, but I assume that was the schoolhouse that had served Betty Town’s children.

By that time, Isaiah Hodge had already died. The house in ruins, as we will see, was evidently that of his widow, Betty Hodge, and the surviving house was that of her son and his family.

If any of Betty Town’s other families remained on the land, John Veritas had not been shown their homes.

After seeing “Aurora,” the visitor compared Rev. Cunningham’s real estate ad to “a patent medicine advertisement recommending pills efficacious in the cures of all diseases …”

John Veritas’s letter in the Raleigh Times elaborated further on his visit to Beaufort County.

According to the local people with whom he spoke:

… a speculating land gambler came down there, fixing his eye upon this spot as an eligible site, turned up a claim to it, and supposing it an easy matter to get clear of these old negroes, he ordered them to leave the premises.”

The “speculating land gambler” was of course Rev. Cunningham.

Evidently, Betty Hodge and her son did not succumb to the minister’s threats. According to the anonymous letter, they even sought out legal counsel from a prominent white attorney in the county seat.

John Veritas continued:

“They were then threatened with violence … A few weeks later, in the bitter cold of December, [Cunningham] procured a lawless vagabond … to undermine the chimneys to the old woman’s house …”

According to John Veritas, Betty Hodge still did not relent.

“Finding this cruel heartless act not sufficient to accomplish his purposes, with a gang of lawless ruffians, at a late hour, on a dark, cold, freezing night, attacked the old house, pulling down portions of it and tearing the roof off, drove the old woman forth exposed to the inclement, freezing frost of a winter’s night ….”

In his letter, John Veritas claimed that Cunningham’s thugs then went next door and “inhumanely beat” Betty Hodge’s son and daughter-in-law. Their crime, he was told, was daring to consult the attorney in Washington about their right to hold onto their land.

At the end of his letter, John Veritas indicated that, according to his friends in Beaufort County, justice was somehow served in the end and “the old woman restored to her land.”

That was not true or, if it was, Betty Hodge did not remain in Betty Town for very long.

By the time the U.S. census taker reached that part of Beaufort County later in 1860, Betty Hodge and her family were not there. I do not know exactly when or how they left, but Betty Town was gone.

I do not feel clear about where they went. According to Bonner’s 1916 history of Aurora that I quoted earlier, they left North Carolina and emigrated to Ohio.

However, I have not succeeded in locating Betty Hodge or any of her family in the federal censuses of Ohio in the late 19th or early 20th centuries. The only mention of them that I have found anywhere was in a brief part of Bonner’s article that I have not yet discussed.

In that section of his article, Bonner writes:

“About 1885 …, some of Isaiah Hodge[‘s] heirs returned, employed E. S. Simmons and entered suit against the citizens of the [Aurora].”

Attorney E. S. Simmons (1855-1907)

Enoch Spencer Simmons was an attorney in Washington, N.C. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A graduate of the University of North Carolina, he was originally from Hyde County, just across the Pamlico River from South Creek.

In 1898, Simmons published a book-length essay called A Solution to the Negro Problem of the South.

In that essay, he proposed that southern whites forcibly remove all of the South’s Black citizens from their land and relocate them to an all-black colony that he proposed the U.S. Government create in the states of Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

I do not think you would be mistaken if you took Simmons’ background as evidence of the quality of legal representation that was available to the state’s black citizens in the late 19th century.

In that 1916 article, R. T. Bonner continued:

“This suit fell through owing to the fact that an unrecorded deed from Sheriff Ellison to Isaiah Respess was found in the safe of Capt. Wilson Farrow who married the only child of Isaiah Respess.”

Isaiah and Betty Hodge’s descendants had not made a claim against Rev. Cunningham, but instead sought damages for what they believed to be the illegal confiscation of their land by Isaiah Respass.

On one of my trips to the State Archives, I looked for the case in the superior court indexes but did not find it. However, I might have missed it; I think it might be worth re-checking.

Few historical records could tell us more about Betty Town, and court filings would also give us a least something from the perspective of the people who lost their homes and land.

The Rev. Cunningham returned to the former site of Betty Town after the Civil War. His claim to the land was recognized by law by that time. Over the next few years, he would welcome new settlers, establish a church, and operate a hotel in the new town of Aurora.

His interests however were rather far ranging. In a New Bern newspaper from 1865, I found an advertisement in which he was selling 1,500 acres of “tar and turpentine land” in Beaufort County.

According to the Charlotte Observer Dec. 5, 1877, edition, he was expelled from the Methodist church district conference for “immorality” in 1877.

The town of Aurora was officially incorporated on the former site of Betty Town in 1880. It grew into a bustling little market town later in the 19th century, and then into an important regional center for truck farming after the railroad’s arrival in or about 1911.

Today Aurora is best known for being home to one of the largest open pit phosphate mines in North America and for a very nice museum that highlights the marine fossils found at the mine.

I do not know if anyone knows more than this about Betty Town. But I hope that I will find out when I publish this story. I cannot help hoping that somebody, somewhere, maybe even a descendent of the people who lost their homes and land, will see this story and reach out to me.