Before composing over two dozen volumes of poetry, before becoming a professor at the prestigious Cornell University in upstate New York, and long before winning any of his numerous national literary awards, Archibald Randolph Ammons was a poor boy working on his father’s Columbus County farm during the Great Depression.

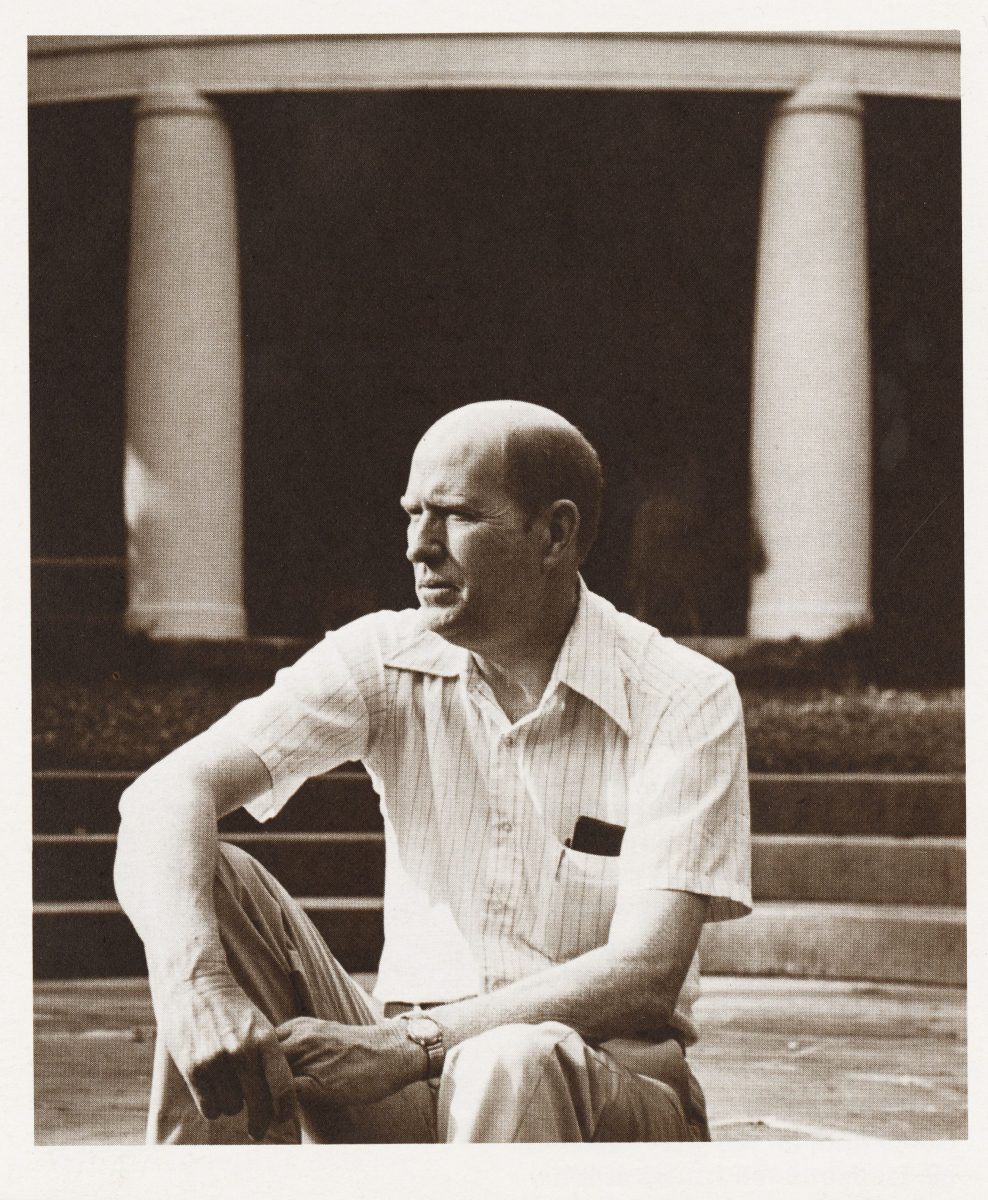

Ammons would eventually achieve fame under the byline “A.R. Ammons,” a heralded poet noted for his beautiful but also scientifically precise descriptions of nature. However, with those who knew him personally, including those who knew him during his formative years in coastal Carolina, he went by the less precise but more identifiable name “Archie.”

Supporter Spotlight

‘Alluvial country’

Archie Ammons was born in his family’s farmhouse just outside of Whiteville on Feb. 18, 1926. The fields he helped his father plow during his youth were 6 short miles from Lake Waccamaw and only 35 miles from the Brunswick County beach communities his family would travel to for the occasional fish fry or oyster roast. Ammons spent these hardscrabble years mostly behind hitched mules, furrowing the soil in which he and his father grew corn, tobacco, peanuts and other cash crops so typical of eastern North Carolina agricultural districts.

Though he would not begin writing poetry until some years later, his experiences on the farm and in what he called the “alluvial country” of the coastal plains impressed him deeply and would eventually find voice in his writing.

For instance, in the poem “Silver,” about a mule his family owned during his childhood, Ammons remembers how he and Silver would “fall soon again into the slow requirements of our dreams / how we turned at the ends of rows without sense to new furrows and went back / flicked by / cornblades and hearing the circling in / the cornblades of horseflies in pursuit.”

In the poem “I’m the Type,” Ammons would look back at his early life on the farm in light of his later career as a famous writer and note how he “misses the mules and cows / hogs and chickens, misses / the rain making little / rivers, well-figured with / tributaries through the / sand yard.” Ammons learned in his childhood to be attentive to the living world around him, including not only the plants and animals but also the physical forces that shape living things. They entered his imagination as a boy and stayed with him the rest of his life.

From the South Pacific to the Outer Banks

According to Roger Gilbert, a professor of English literature at Cornell University who is writing a biography of his former colleague, the Ammons family farm was not particularly successful, so a young Ammons sought employment in the largest nearby city.

Supporter Spotlight

“He had been working in the shipyards in Wilmington after high school and one day he came home and the farm had been sold,” Gilbert said in a recent interview. “That farm had been his world growing up. So when that was gone, when it was no longer a place that belonged to him, I think he felt he’d lost that sense of having a home.”

This bitter loss began a whirlwind period in Ammons’s life. American involvement in the Pacific theater of World War II was ramping up just as he graduated high school. With no more family farm to tend, Ammons enlisted in the Navy. He was deployed as a sonar operator aboard the destroyer U.S.S. Gunason, on which he sailed through the South Pacific, listening for the pings of reverberating soundwaves that could signal the underwater presence of enemy vessels or weapons.

It was also during this time, on the long voyages at sea, that Archie began writing his first poems. He was training the precision of his ear in more ways than one.

When the war ended, the poor country boy from Whiteville took advantage of the GI Bill to attend Wake Forest College. Ammons graduated in 1949 and left town with a Bachelor of Science and, more importantly, a courtship with his future wife, Phyllis.

He moved almost immediately to the Outer Banks village of Hatteras, where he would spend the 1949-50 academic year as principal of tiny Hatteras Elementary School — and where Phyllis would join him after their wedding during Thanksgiving break.

Though he was only on the Dare County island for a year, the dramatic seascapes of the Outer Banks entered his poetic imagination just as the sandy farmland of Whiteville had. In an unpublished poem written during his first summer on Hatteras, and kindly provided by Professor Gilbert out of the Ammons archive at Cornell University, Archie tried to capture in words the strange magic of the Banks at night: “Night has come to this small island, / Drowsing on the golden dunes cool-mist opiates. / Far out at sea, a ship’s sea-lantern sways / And a lost gull screams.”

Gilbert noted that Ammons, by this point, had not yet found his unique poetic voice. But “the Hatteras landscape stayed with him and influenced some of those early poems,” he said.

A Second Vision of Land and Sea

By “those early poems,” Gilbert was referring to Ammons’s first collection of poetry, “Ommateum,” which he self-published in 1955. By this point, Ammons was living in New Jersey and working at his father-in-law’s manufacturing firm, which made glassware for laboratories.

In “Ommateum,” Ammons began to dabble in the scientific specificity and abstraction that would later become a hallmark of his style. More central to his first book, however, is one of Ammons’s mainstay themes: the transience of nature and human life.

In fact, the very first poem in “Ommateum” draws on the windswept ecology of Cape Hatteras to show us a narrator, Ezra, seeking his voice amid a powerful vortex of natural forces. Reworking many of the specific images and themes of his unpublished poem from his year in Hatteras, Ammons describes how Ezra speaks his name to the sea, “but there were no echoes from the waves / The words were swallowed up / in the voice of the surf.” The protagonist has to turn away “from the wind / that ripped sheets of sand / from the beach and threw them / like seamists across the dunes.”

Finally realizing the futility of fighting the wind, Ezra decides instead to adapt to and even become part of the landscape. “So I Ezra went out into the night,” the poem ends, “like a drift of sand / and splashed among the windy oats / that clutch the dunes / of unremembered seas.”

The poem sets the tone for the rest of the volume and, in a way, for the rest of Ammons’s career. It is somehow fitting that a poet from coastal North Carolina would begin his first book looking for meaning in a sea squall.

According to Alex Albright, a retired professor of creative writing at East Carolina University and the editor of the indispensable Ammons volume “The North Carolina Poems,” “There’s a journal entry from when (Ammons was) in the Navy that provides a controlling metaphor for his life.”

“He sees off in the distance the fine line of the horizon,” Albright said in a telephone interview, “and as he gets closer and closer to it, it’s not really a straight line. It’s that second vision that he brings to a lot of his landscapes.”

Becoming a classic

“Ommateum” sold barely any copies when it first appeared. But little by little, Ammons began making inroads into the professional poetry establishment. Individual poems started getting picked up by journals and magazines here and there throughout the 1950s, and in 1964 he was hired to teach poetry writing at Cornell University, where he would later become a full professor and befriend Roger Gilbert.

The same year also saw the publication of his second collection, “Expressions of Sea Level,” this time by a major university press. From that point on until his death in 2001, Ammons would never go more than four years without releasing a new volume.

From the 1970s through the end of the 1990s, Ammons’s star rose without cease. He won the National Book Award for one collection of poetry in 1973, then the prestigious Bollingen Prize for Poetry for a different collection in 1975. It was around this time that the influential literary critic Harold Bloom said that “No contemporary poet, in America, is likelier to become a classic than A.R. Ammons.”

As if to prove Bloom’s point, Ammons released a volume in 1981 that received the National Book Critics Circle Award, and another volume 12 years later that won him his second National Book Award. In October 2000, just five months before his death at age 75, he was inducted into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame.

Albright, who knew Ammons personally through their work together at the North Carolina Literary Review, pointed out that the shy, affable farm boy from Whiteville was aware he had a gift.

“He knew that he was in a rare class,” Albright said. “He had a Southern way of deflecting praise, but there were very few poets that he imagined were as good as he was.”

Not Deep down but across

Ammons is by no means omnipresent in Whiteville today, but neither is he or the world of his childhood totally forgotten. His family home was torn down years ago, but Whiteville High School has a couple of old buildings he would have sat in as a student in the 1930s, and the Pentecostal church he attended with his parents still stands out by Spring Branch. There is no plaque for him in town, but the Reuben Brown House, a historic preservation group in Columbus County, runs an annual poetry contest in his honor.

The fields and swamps he roamed as a boy are in a similar state of in-between. “Until very recently he would have recognized the Columbus County landscape,” Albright said. “The bridges are a little better, but it’s still swampy. There’s still bugs, it’s still quiet, and you’re still really close to the coast out there.”

According to Albright, even the Brunswick County beaches of Ammons’s youth have not yet been totally transformed.

“There’s a little place when you go to the right on Ocean Isle, that’s where they went for their oyster roasts,” he said, “and on the back end, you can sort of forget that the high-rise bridge is going over to Ocean Isle, and it can feel very isolated.”

Still, Ammons was powerfully attentive to and protective of the natural world. The poet would likely have some strong opinions about the lack of care taken for the soil, water, trees and animals of southeastern North Carolina if he saw it today.

“He could be looked at as an early environmentalist,” Albright said of his old friend. “His feel for the land was just something. And part of what he would see would be heartbreaking. The factory tree farming, especially.”

In “Making Fields,” one of his most moving poems about his North Carolina roots, Ammons describes the give and take between the land and his ancestors who worked that land going back to his father’s father.

The life he presents to readers in this poem is a hard one, and it unfolds overtop a thin coastal soil stratum that doesn’t always offer bounty and wealth. But at the end of the poem, Ammons can still clearly see and hear his connection to the place of his birth.

“… the land is not deep down but across, as into time” he writes. “the runs, the / ditch banks, the underbrush, the open fields with a persimmon tree / or wild cherry call, they call me.”