“Pretty much all my paintings tell a story,” said Rik Freeman.

“When I was growing up, my grandmother used to say I would eavesdrop on grown folks’ conversations because they were just always so colorful and talking. I would see images in my head of what they were talking about and everything said,” the Washington, D.C., artist told Coastal Review.

Supporter Spotlight

For the last few years, Freeman’s art has been telling the story about African American beach communities during the Jim Crow era.

His series, “Black Beaches During Segregation,” features several vibrant paintings representing different historically Black beaches on the Atlantic, including Ocean City on Topsail Island, and goes on display in Onslow County starting Saturday.

The exhibit is part of the 15th annual Ocean City Jazz Festival set for July 4-6 in North Topsail Beach. The theme of the three-day music festival is “Celebrating History Through the Language of Jazz and Unity.” A full schedule and ticket information can be found on the website.

The festival was first held in 2009 to mark the 60th anniversary of Ocean City’s establishment. Now a part of North Topsail Beach, Ocean City was established in 1949 “as an African-American-owned community 15 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Ocean City was a unique community as it was the first residential beach community with Black home ownership in the state,” according to the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission, which is sponsoring the exhibit with Ocean City Jazz Festival.

Supporter Spotlight

Opening reception for Freeman’s show is at 2 p.m. Saturday, June 28, at the Jacksonville-Onslow Council for the Arts, 826 New Bridge St. in Jacksonville. Freeman is scheduled to give an artist’s talk at 3 p.m. and there will be time afterward to view the exhibit. Register online to attend.

Freeman, who spent his youth in Athens, Georgia, said he began drawing as a young child but really got into murals in his 20s, after college. He moved to Washington, D.C., in 1985 when he landed a job at the airport while he was visiting family for Thanksgiving.

He returned to art a few years later at 32. “It was in ’88. My father died — this is about to sound like an old blues song — my father died. I got fired from my job. My girlfriend left me, so I started working back with my art again,” he said.

The D.C. Commission of the Arts and Humanities posted in the newspaper an ad looking for artists willing to work with children during a summer program painting murals. Freeman applied and was accepted. “It started from there,” making a living off painting murals.

The idea for the “Black Beaches During Segregation” series was sparked when he learned that a Black-owned beach in California, which was taken from the family owners in the 1920s, had been returned to the descendants.

“I thought about that and that couldn’t have been the only one,” Freeman said, so he began researching. He came across Chicken Bone Beach, an African American beach in Atlantic City, New Jersey. He asked Honfleur Gallery owner Duane Gautier, who is from the Garden State, if he knew about the beach, but hadn’t heard of it. “And so I started telling them about others.” Freeman’s work is shown at Honfleur Gallery in Washington.

Gautier was interested and told Freeman to write a proposal for the gallery’s Artist in Residence Program. This was in 2022.

He started with six beaches along the Atlantic Seaboard to research and paint, including Ocean City. He’s up to 14 or 15 beaches now, and he wants to represent at least one beach in every state south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

During his visit to Ocean City, Freeman met with people of the community, including Ocean City Jazz Festival co-chairs Carla and Craig Torrey.

Carla Torrey, originally from Fayetteville but now residing in Durham, is a second-generation homeowner in Ocean City. Her father was the principal builder when the community first started.

When she and others met Freeman in person, Torrey said that he explained how his series “uses art to visually document and celebrate the historical and cultural importance of places like the Ocean City Beach community, which played a crucial role in providing spaces for leisure and community for African Americans during a time of systemic racial discrimination. We are a perfect match.”

The exhibit features two paintings honoring Ocean City. One is based on a photo Torrey gave Freeman of herself as a young girl walking with her father on the pier with Ocean City Terrace in the background. Built in 1953 from an abandoned Navy missile observation tower, the restaurant is no longer standing.

“It’s so special to me, because my father really loved this community,” Torrey said. “I’m very grateful to Rik for doing that.”

She said that after talking to Freeman, the jazz festival organizers felt the series should be brought to the county, “so that they could see the other communities that he had visited and that existed and learn a bit about their legacy in history.”

The other painting features two men playing instruments with a modern-day interpretation of the Ocean City Terrace in the background. Freeman said he thinks they eventually want to get restaurant rebuilt, so he took artistic license when painting the building.

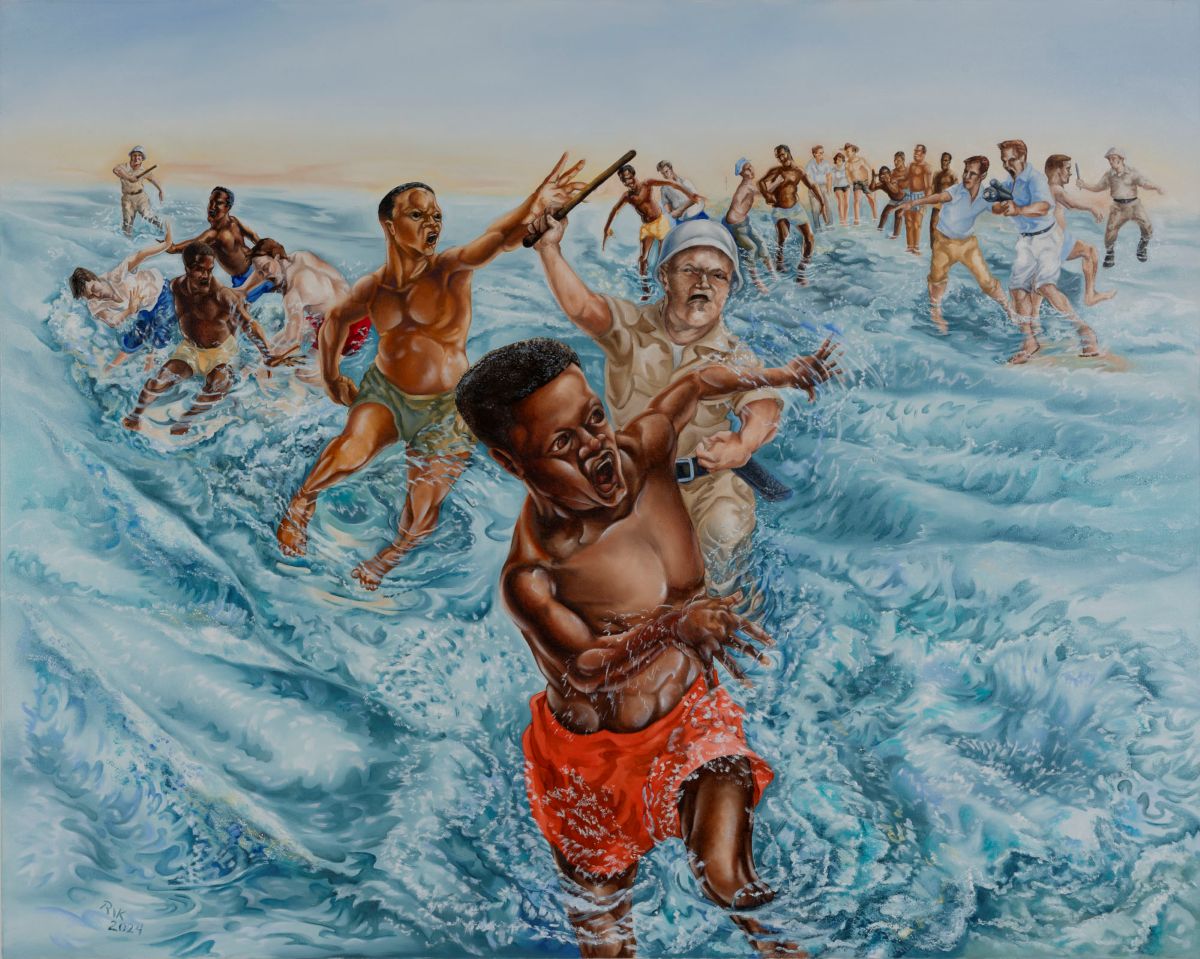

The piece on St. Augustine Beach in Florida, Freeman said, is the only piece that directly confronts the racism of the era.

“Because in June ’64 in St. Augustine, they had, instead of sit-ins, it was a wade-in because you’re wading into either a pool or a segregated beach, and a riot broke out, and a lot of people got injured. It was on the news,” Freeman explained. Around the same time, a motel owner threw sulfuric acid in a pool where high school kids were swimming because they wouldn’t get out of the water.

“Those two incidents led (President Lyndon Johnson) to sign the Civil Rights bill less than a month later. So, I figured I wanted to do at least one piece that did show that out-and-out racism, but most of the pieces are based on showing the joy, the camaraderie, you’re in a safe place, and people just having a good time,” he said.

“But the underlying thing is,” Freeman continued, is that when somebody’s looking at the work and they “say, ‘why is it just all these Black folks at the beach?’ Is this somewhere in the Caribbean, or is it Brazil, Africa?’ No, this is United States of America, and the beaches were segregated.”

In his painting depicting Atlantic Beach in South Carolina, “you can barely see it. You have to look for it. There’s a little orange rope that goes out into the water. And a lady down there was telling me that rope was basically the color line, and she just kind of laughed. She said, ‘What did they think that the water that touched us wasn’t going to come and touch them?’”

Ultimately, Freeman wants people who see the exhibit to see the camaraderie and look at the histories of these beaches.

“I want people to kind of look and see as it’s very commendable what people were able to do to be able to create those beaches and safe places. And you know, some of them had a little bit of trouble and everything, but by and large, they were safe,” he said.

Torrey said that the Ocean City Jazz Festival “provides the perfect historical setting and audience for Rik Freeman’s impactful art, while the NC African American Heritage Commission brings its expertise and mandate for preserving and promoting the rich, often untold, stories of African American heritage in North Carolina.”

North Carolina African American Heritage Commission Director Adrienne Nirdé has been with the state commission since 2020, acting as director for the last two years.

The commission has sponsored the Ocean City Jazz Festival for several years now, which Nirdé said is important for the division within the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

“When talking about segregation and Civil Rights, that’s often associated with lunch counters and schools, and that’s a big part of the history that people learn about, if they learn about it at all, but when you dive into deeper, in a place like North Carolina, this was something that touched every aspect of life,” Nirdé said. “People were recreating. They wanted to go on vacation, they wanted to go to the beach. They wanted to golf and experience swimming pools and all of these different types of spaces. This is just really an important way to share the other layer of this story.”

Council For the Arts of Jacksonville Onslow County Executive Director Kandyce Quintero said she and the council’s executive board “are extremely excited to have this exhibit be the kick-start to the festival this year.”

During Freeman’s talk on Saturday, he said he will discuss the work he curated for this exhibit.

“I really want the visitors to understand how important these paintings are. The stories behind each one and how generations have been affected even in today’s world,” she said.