The two agencies that enforce fisheries rules in North Carolina waters said they are ramping up their outreach to prepare commercial and recreational fishermen for the divisive mandatory harvest reporting laws that are to go into effect later this year.

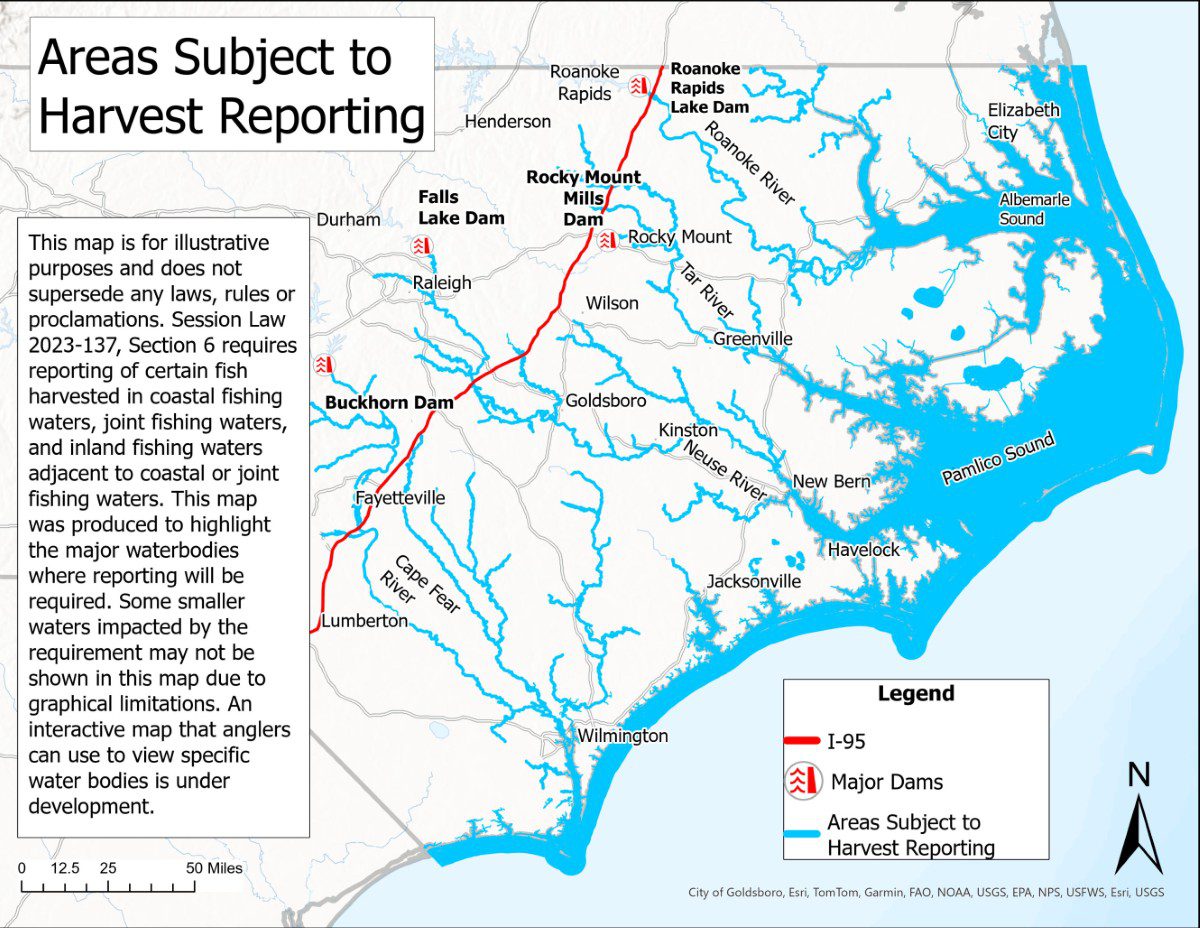

Starting Dec. 1, all red drum, flounder, spotted seatrout, striped bass or weakfish recreationally harvested in coastal, joint and some inland fishing waters must be reported at the end of each fishing trip to the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Marine Fisheries, which manages coastal waters. Wildlife Resources Commission manages inland waters and the two manage joint waters together.

Supporter Spotlight

“The five species are among the most targeted fish in North Carolina coastal and joint fishing waters, and inland fishing waters adjacent to coastal and joint fishing waters,” according to the division.

The law affects commercial fishing license holders as well. In the past, those with a commercial fishing operation were required to report only what they sold to a dealer but starting Dec. 1, they must report everything harvested, including finfish, shellfish and crustaceans, no matter if it’s sold or kept for personal consumption.

“The mandatory harvest reporting system for both commercial and recreational fishing is due Dec. 1,” and the department expects the data collected to be “very useful as we estimate what the existing fish populations are and what the trajectory looks like for those populations,” NCDEQ Secretary Reid Wilson told the about 150 at the Coastal Summit held last week in Raleigh.

The North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review, hosted the summit April 9-10 in the Marbles Kids Museum.

Public outreach

Marine Fisheries Public Information Officer Patricia Smith explained during an interview that “we’re just really trying to get the word out.”

Supporter Spotlight

Division of Marine Fisheries staff have met with the for-hire industry, had a presence at fishing trade shows to bring people up to speed on the new requirements, have been passing out stickers with a QR code for the harvest reporting page during special events, and will post signs once they’re made at public boat ramps and other places where recreational fishermen gather.

In addition to pushing public awareness, Smith said the reporting webpage on NCDEQ’s website has been launched. So far, there’s background on the rule, a frequently asked questions section and the reporting tool that people can use now on a voluntary basis. The webpage is being continuously updated to make it as user friendly as possible, particularly for people using their phone to submit their form.

Anyone who would like to have division staff talk about to their group about the requirements should contact the division to set up an in-person or virtual meeting.

The hope for the program in the long run is that a “dynamic app of some kind with recreational outreach along with the reporting requirements” will be developed,” Smith said.

Smith said that another facet of the mandatory reporting is that it gives “fishermen a greater understanding of what their role is in fisheries conservation.”

For example, many fishermen ask how the one fish they harvest can affect an entire fishery. But if a million people catch just one fish, that adds up to a million fish being removed from the population. Plus, a certain percentage of fish that are caught and thrown back die.

“We do hope that this (program) is something that will help them realize their role in it,” Smith said.

The division is being supported in the outreach effort by the Wildlife Resources Commission.

The Commission’s Coastal Region Fishery Supervisor Ben Ricks told Coastal Review that the mandatory harvest reporting for red drum, flounder, striped bass, spotted seatrout and weakfish may provide an effective tool to better manage these fisheries.

“A critical component to its effectiveness is the participation of everyone. Accurate harvest data will lead to better overall estimates of mortality and more informed decision making,” Ricks said.

Enforcement will be phased in over the next three years. From Dec. 1, 2025, to Dec. 1, 2026, those who fail to report their harvest will be given a verbal warning. The next year, a warning ticket will be issued, and starting Dec. 1, 2027, the penalty for not reporting a harvest is an infraction with a $35 fine. Infractions can lead to having fishing licenses and permits suspended.

The division’s Marine Patrol and Wildlife Commission’s officers enforce the rules in their respective waters.

About the rule

The law was put in motion by the North Carolina Marine and Estuary Foundation a few years ago. The nonprofit said in 2024 that it had worked with state legislators and conservation partners to develop the language for the “groundbreaking” legislation that is “aimed to fill data gaps in order to provide a better understanding of how fish are harvested from our coastal waters.”

The North Carolina General Assembly approved the mandatory reporting requirements in 2023. The law set the effective date as Dec. 1, 2024, and the division was awarded a one-time allocation of $5 million to build the reporting system.

The legislature’s mandatory harvest reporting requirement reads: “Any person who recreationally harvests a fish listed in this subsection from coastal fishing waters, joint fishing waters, and inland fishing waters adjacent to coastal or joint fishing waters shall report that harvest to the Division of Marine Fisheries within the Department of Environment Quality in a manner consistent with rules adopted by the Marine Fisheries Commission and the Wildlife Resources Commission. The harvest of the following finfish species shall be reported: (1) Red Drum. (2) Flounder. (3) Spotted Seatrout. (4) Striped Bass. (5) Weakfish.”

The Division of Marine Fisheries carries out rules the Marine Fisheries Commission establishes for coastal and joint waters and the Wildlife Resources Commission carries out regulations determined by its 20 or so commissioners for inland and joint waters.

There was pushback throughout the rulemaking process in 2024. Both agencies were inundated with thousands of comments, a fair amount laden with expletives, which Coastal Review reported at the time, during one of the public comment periods.

Division staff asked for a one-year extension, which the General Assembly approved in 2024. Then-Gov. Roy Cooper declined to sign the bill at the time because of unrelated provisions.

Smith explained that the division asked for the year extension to allow time to set up the reporting program and to allow for public outreach “because this is not just coastal folks. It’s coastal joint waters and any inland waters that are adjacent to coast to joint waters. So basically, it’s any of these waters in the state where you’re going to find these species.”

Coastal Review will not publish Friday, April 18.