Third in a series

A chemical manufacturer that discharged pollutants directly into the Cape Fear River for decades has asked a judge to keep thousands of documents out of the public eye.

Supporter Spotlight

Attorneys for Chemours and its predecessor company DuPont requested the court keep under seal mostly internal communications between company employees about “non-public facts” that largely pertain to chemical production, according to the motion filed Feb. 28 in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina.

“The court has recognized that this exact type of information is competitively sensitive because, in the hands of a competitor, it could be used to disadvantage Defendants,” Chemours’ attorneys argue.

Their appeal to the court aims to shield from the public between 5,000 and 10,000 pages of documents the plaintiffs’ lawyers submitted in their case against the companies, according to an attorney representing public utilities and local governments downstream of Chemours’ Bladen County plant.

“We do not believe there is a good basis for the vast majority, if not all, of those documents to be under seal,” said attorney Bill Cary of Brooks Pierce Law Firm.

The firm represents Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, Brunswick County, Lower Cape Fear Water & Sewer Authority, and Wrightsville Beach, which sued the companies in October 2017.

Supporter Spotlight

The lawsuit aims to recover costs and damages associated with the Fayetteville Works’ plant’s discharges of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, for decades into the Cape Fear River, the drinking water source for tens of thousands of residents in the region.

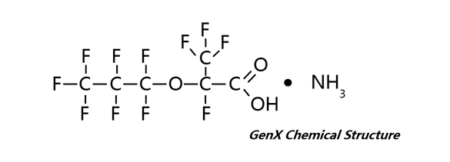

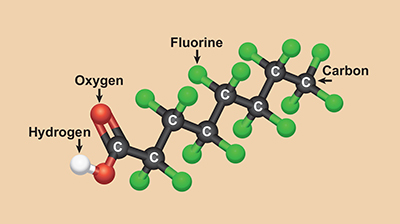

PFAS are a group of more than 14,000 chemicals used in everyday consumer products including food containers, stain-resistant carpet and water-repellant gear. These man-made chemical compounds are persistent in the environment and have been found to accumulate in humans and animals. Exposure to these substances has been linked to weakened immune function, reproductive and developmental issues and increased risk of some cancers.

Included in the 25,000 pages Brooks Pierce has submitted to the court is a history of dealings Chemours’ West Virginia-based Washington Works Facility has had with PFAS, Cary said.

“Many of the documents that they have identified as wanting to be sealed are already on the public record, which means that there is no reason to seal them,” he said. “They’re already public knowledge. They are either part of the (Environmental Protection Agency) public record or they have been exhibits in other files.”

The Washington Works’ plant historically used synthetic compounds perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, commonly referred to as C8, and GenX, in its manufacturing processes. The plant produces resin used to make the semiconductors that power cellular phones, computers and other electronic systems.

For decades, the plant’s owners knowingly discharged C8 into the Ohio River, the drinking water supply for an estimated 5 million people. High levels of the chemical were found in public drinking water supplies and private drinking water wells downstream of the facility, prompting government intervention and a slew of lawsuits.

Earlier this year, the West Virginia Rivers Coalition, a statewide nonprofit, filed a federal lawsuit seeking a temporary court order for Chemours’ Washington Works facility to reduce its discharges of GenX into the Ohio River. The lawsuit alleges the company is exceeding its permitted discharge limits.

As part of a 2019 consent order with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality and Cape Fear River Watch, Chemours has spent millions taking steps to reduce its emissions of PFAS into the Cape Fear, the ground and the air. The consent agreement also charges the company with testing thousands of private water wells in the region and providing a means of uncontaminated drinking water to households with private wells that contain elevated levels of PFAS.

The brunt of costs associated with removing PFAS from raw water sources has fallen on downstream drinking water suppliers, including Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, or CFPUA. The utility has spent millions in upgrades to filtrate PFAS out of the drinking water it provides to customers in the Wilmington area. The average customer bill includes a $7.50 charge associated with the utility’s filtration system.

A CFPUA spokesperson referred questions to Cary.

An upgrade and expansion of Brunswick County’s Northwest Water Treatment Plant totaling more than $120 million is expected to go online late this spring. The project includes the installation of an advanced low-pressure reverse-osmosis treatment system to remove compounds including PFAS and 1,4-dioxane, the latter of which is a likely carcinogen that is also being discharged into the Cape Fear River by upstream polluters.

“The health of the Cape Fear River is of importance to everybody in the watershed and they should be informed about it,” Cary said.

Emily Donovon, co-founder of Clean Cape Fear, said in a telephone interview earlier this week Chemours and DuPont had spent decades “hiding” its discharges of PFAS into the Cape Fear River at the expense of residents living downstream of the Fayetteville Works plant.

“We’re not just talking about monetary expenses,” she said. “We’re not talking about utility costs. We’re talking about the fact that people are dying. People have died. People died not knowing if what that company did and that facility did caused their illness to accelerate or cause them to get sick in the first place. We deserve to know everything that this company did. Out of basic human decency, we deserve to be able to see those files and we deserve to be able to know exactly what was going on. History needs to know this.”

Clean Cape Fear on Thursday afternoon posted an online petition for members of the community to sign in support of unsealing the documents.

Cary described information in the documents the companies want to remain sealed as “embarrassing” internal documents that include communications among Chemours employees.

“Or I would be embarrassed if I was Chemours,” he said.

An attorney with Miami-based Shook, Hardy and Bacon, LLP, the law firm representing The Chemours Co. FC, E. I. Du Pont De Nemours and Co., and The Chemours Co., did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

In their request to keep documents sealed, the attorneys argue Brooks Pierce violated electronic filing rules, writing, in part, that the plaintiff’s “indiscriminate inclusion of large swathes of immaterial documents” place “an undue burden on Defendants in responding and preparing this motion.”

Chemours’ attorneys go on to write that it would be impractical to redact the “enormous volume” of documents Brooks Pierce included in its Jan. 17 motion for summary judgment, or a request of the court to rule for one party against another party without a full trial.

Brooks Pierce has until April 14 to respond to the motion.

“We will respond to the motion that day,” Cary said.

In 2023, CFPUA filed a separate lawsuit in Delaware’s Court of Chancery to stop DuPont, Chemours and their related spinoff companies from financial restructuring, a move that would allow the companies to avoid liability for damages resulting from PFAS contamination. The case has been stayed pending the outcome of the 2017 lawsuit.