Update Feb. 5: The Fort Raleigh National Historic Site shoreline stabilization public meeting has been rescheduled for 6 p.m. Wednesday, Feb. 12. The comment period was extended to Feb. 21 because of the weather-related meeting postponement.

Update 8:45 a.m. Jan. 23: National Park Service officials announced Wednesday night that the shoreline erosion public meeting, originally scheduled for Thursday has been postponed because of hazardous weather conditions. A new date will be announced.

Supporter Spotlight

Original post:

For the first time in close to 50 years, National Park Service officials are looking to stabilize the eroding shoreline at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site that, if not addressed, could jeopardize the cultural and natural resources stewards of the 355-acre site in Manteo aim to protect.

Park service staff are considering three different structures to protect the about a mile of shoreline and invite the public to share their thoughts through Feb. 7.

Established in 1941 on the north end of Roanoke Island where the Albemarle, Croatan and Roanoke sounds converge, Fort Raleigh is the last known location of the 116 English settlers that disappeared in the late 1580s, referred to as the “Lost Colony.”

Before Sir Walter Raleigh led English expeditions to the “New World” in the late 1580s, the land was home to Carolina Algonquians. During the American Civil War in the 1860s, formerly enslaved people established the Freedmen’s Colony on the island nestled between Manns Harbor and Nags Head.

Supporter Spotlight

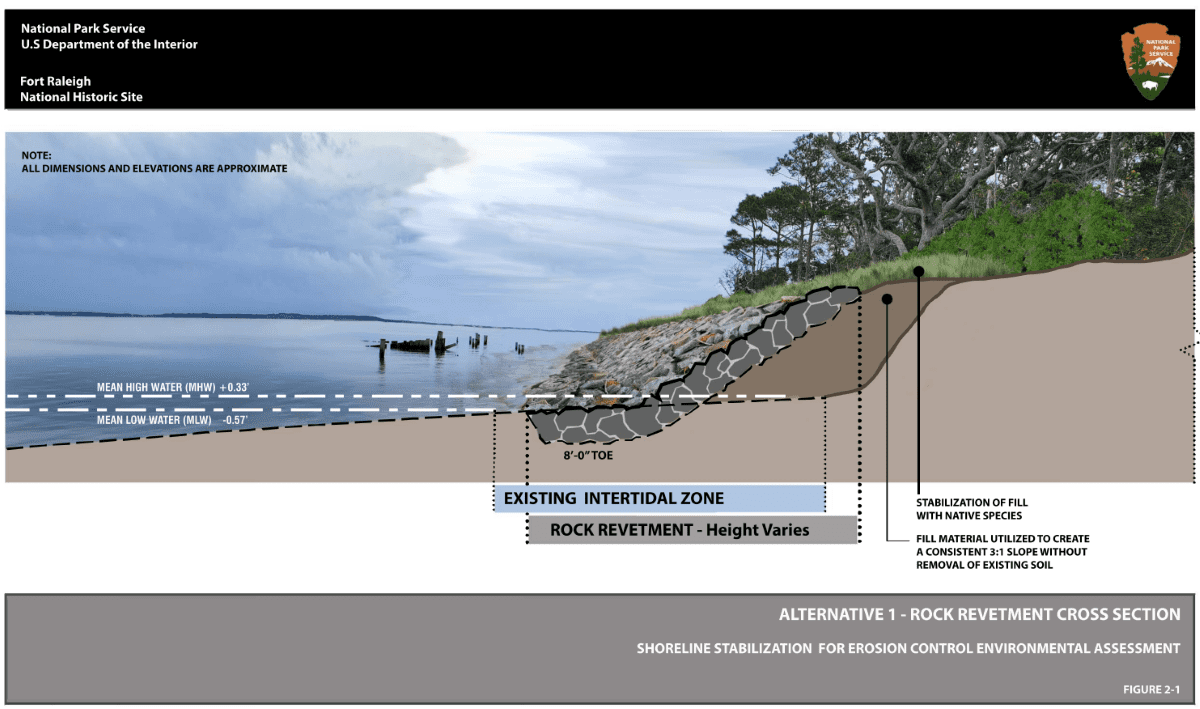

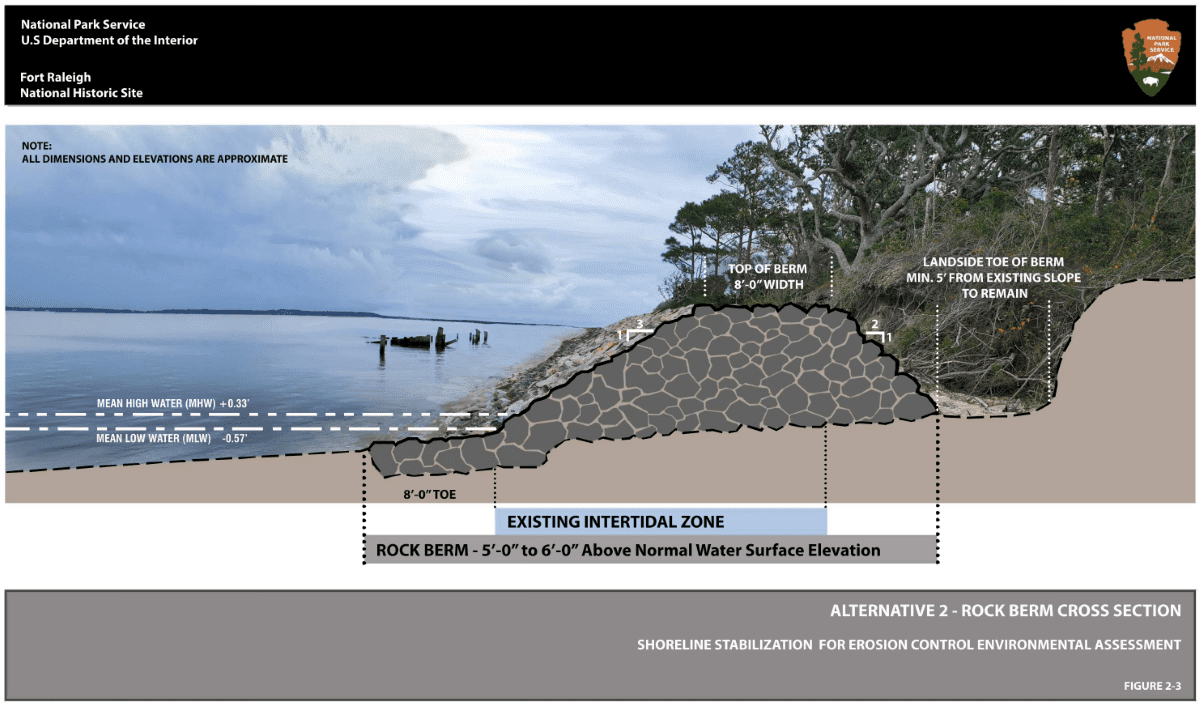

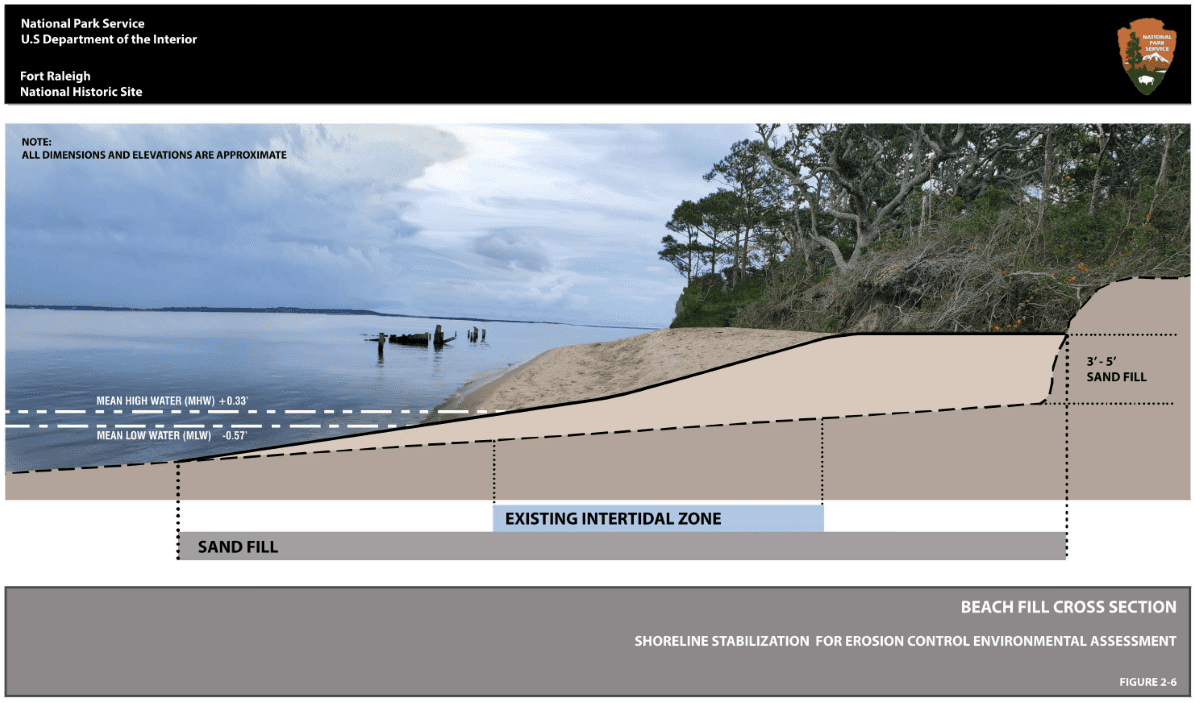

The alternatives detailed in the public scoping newsletter include a rock revetment against the shoreline escarpment with fill material to create a slope; a 5- to 10-foot-high rock berm with a 20- to 40-foot-wide base at the toe of the existing slope on the beach possibly backfilled with natural materials; or a site-specific combination of the two along the mile stretch.

Comments can be submitted electronically or by mail to: Superintendent, 1401 National Park Drive, Manteo, NC 27954. The comment period began Jan. 8. A public meeting on the project is set for 6 p.m. Thursday at the site’s visitor center, 1500 Fort Raleigh Road, Manteo.

Project documents indicate that erosion has been an issue since the park was established. Wooden groins were built in the 1940s along the shoreline, and in the 1960s, an offshore breakwater was installed.

In the late 1970s, around 1,500 feet of riprap was placed near the Dough Cemetery, which dates to the mid-19th century and faces the Croatan Sound, and along the shoreline around the Lost Colony Waterside Theater, where “The Lost Colony” dramatization of the 1580s interaction between the Algonquian and English has been performed nearly every summer since 1947.

Mike Barber, public affairs specialist with the National Park Service, said that 1979-80 work was the last shoreline-stabilization project at the cemetery and theater, and no maintenance of existing shoreline-stabilization measures has taken place to since, as far as anyone seems to know.

“Erosion along the remaining exposed shoreline, including 4500 feet of unstable, undercut cliffs as high as 25 feet, poses a serious threat to potential archeologically significant sites and park facilities,” the scoping newsletter states. “Without action, the erosion will most likely continue, causing continued loss of park lands, vegetation, archeological resources, and ultimately park facilities such as roadways, parking areas, and buildings.”

Barber expounded that, right now, mature trees near the shoreline are falling, and potential archeological resources may be washing away without intervention.

Barber said that the Waterside Theater parking lot, Pear Pad Road and the utilities that run along it as well as the National Park Service employee housing on the southern side of the road are along segments of shoreline that have not been stabilized and are the most vulnerable.

The three alternatives were determined using data from previous related studies, evaluating existing topographic conditions, and assessing existing jurisdiction, and “A preferred alternative has not been selected to date,” he said.

He added that the environmental assessment “is being developed to analyze the impacts of each alternative to guide the selection of a preferred alternative based on environmental impacts to the historic site’s natural and cultural resources.”

An environmental assessment evaluates the potential environmental impacts of a proposed action and is required by the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA.

Barber said that the environmental assessment is expected to be released for public review this summer with a goal of publishing the final version before the end of the year.

Barber said that if all goes as planned, it may be several years before project work begins.

“Prior to starting a project to stabilize the shoreline, we will need to finalize — with public feedback — the environmental assessment, enter into a contract to design the stabilization based on the selected alternative, and hire a contractor to perform the stabilization work,” he said.

Michael Flynn, physical scientist for the National Park Service, explained that while they don’t have an estimate of shoreline change since the 1940s, a1972 study reported that the northern end of Roanoke Island may have receded by as much as 928 feet from 1851 until 1970, losing around 7.25 feet a year, and 158 feet from 1903 to 1971, or around 2.32 feet a year.

More recent shoreline change rate data is provided within a park service technical assistance report published in 2010. That report describes the segmentation of the shoreline that took place because of stabilization methods employed between 1950-1980, Flynn said.

The report cites a 2003 study that estimates erosion rates for unmodified bluff segments between highly modified sediment bank shorelines is as high as 21 to 23 feet a year between 1969 and 1975, which motivated the riprap placement in 1980.

Natural rates of erosion along unmodified segments are estimated to be between 2 and 3 feet a year, with more severe rates of erosion located down drift of stabilization methods, Flynn explained.

Flynn said that the park is generally planning for a foot of sea level rise in the next 30 years based on the Sea Level Rise Technical Report released in 2022. He said park officials recognize that sea level rise will increase the frequency and magnitude of flooding and storm surge, exacerbating erosion and its impacts to resources and infrastructure.

“Specific sea level rise scenarios used for engineering designs will be selected following the completion of the (environmental assessment),” he said.