Hotels have been a staple of the North Carolina coastal vacation for over a century. There are hundreds along the coast today stretching from the Corolla Village Inn near Virginia to the Continental Motel at Sunset Beach, over 200 miles to the south.

The first famous North Carolina hotels, all open by the early 1900s, included the Lumina Pavilion in Wrightsville Beach, the Atlantic Hotel in Morehead City, and the First Colony Inn in Nags Head. These hotels drew thousands of tourists each year and shaped the landscape around them, with the Lumina giving its name to one of Wrightsville Beach’s main thoroughfares.

Supporter Spotlight

But one of the more popular hotels of the early 20th century is almost forgotten. No old ruins survive of the Bayview Hotel in the tiny unincorporated Beaufort County community of Bayview, and there are no historic markers other than an illustration on a small wooden sign.

The Bayview was a unique hotel, a river-based beacon that helped build a tourist center in an area mainly known today for agriculture and fishing.

The tourist hotel boom began in the late 19th and early 20th century. People had visited North Carolina beaches since the early years of the colony, but it took until the late 1800s for railroad construction and growing industrial prosperity to create a steady stream of tourists. Once they had the money and the ability to reach the state’s beaches, North Carolinians and out-of-staters came in droves.

In 1921, a travel writer for the New York Tribune noted, “there is one of the finest white sand beaches at Wrightsville that I know anything about,” and spent the rest of a long article praising the town’s Lumina Pavilion.

Eastern North Carolina tourism during this period was centered on beach travel, as it is today, but there were plenty of other scenic areas near the coast that could become tourist destinations. This thought animated the Bayview Hotel founders, a group that included businessmen from Washington, Wilson and other eastern towns. These men had connections in several different industries, most notably coastal businesses such as seafood processing.

Supporter Spotlight

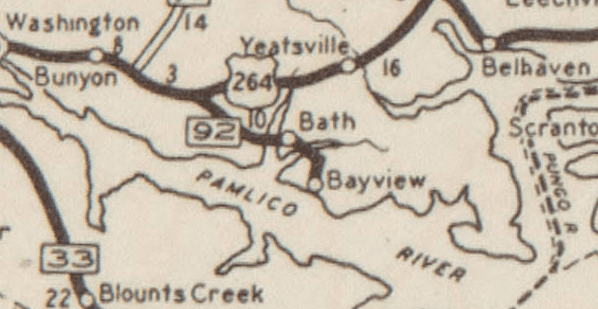

They spent about half of a million dollars to establish their hotel on the Pamlico River 19 miles down from Washington and 3 miles south of Bath. The area had been mostly untouched prior to that point and was known more for hunting than any other pursuit. But it had beautiful views of the water and was a perfect spot for sunbathing, swimming, and lounging away from crowds and cities.

The planners went through every effort to make the Bayview Hotel an attractive destination. They laid out a large boardwalk with concessions and a golf course. Steamships made regular excursions between Washington and Bayview. Once they arrived, guests enjoyed modern plumbing, electric lights, and regular dances held on an expansive pavilion. A 1927 newspaper advertisement showcased Bayview as a center for “bathing, boating, dancing, fishing, and many other amusements.”

The Bayview Hotel thrived for nearly two decades. It hosted a number of dignitaries including longtime Congressman Lindsay Warren, Senate Leader Furnifold Simmons, and the then-former Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, the noted newspaperman and white supremacist.

But the Bayview was subject to the same threats that other hotels of the time had faced, notably fire. Despite the extensive brickwork used in the hotel’s construction, it burned down in 1943, just as the famed Atlantic Hotel had in Morehead City in 1933. The loss hit the area as the country was in the midst of fighting World War II and lacking the resources to rebuild a hotel as large as Bayview.

Following the war, the tourism industry forgot Bayview and other river towns in favor of the beach. Bayview was passed over for interstate highway construction and could only be reached by the two-lane N.C. Highway 92, which is entirely contained within Beaufort County.

The one notable connection that Bayview has today, the ferry across the Pamlico River to Aurora, was built not for tourism but for employees of the Aurora phosphate mine Texas Gulf Sulfur that opened in the 1960s. The hotel was never rebuilt. In subsequent decades, the land where it was became the home of a community, Bayview Townes, which features a painting of the original hotel on its sign.

The Bayview Hotel is a symbol of an earlier time, before the era of highways, roadside motels, and the state’s mountain-beach dichotomy. It was a time when new business ventures could create tourist centers out of swamp and woods. Fueled by railroads and early car travel, the Bayview Hotel was able to carve out a role in the history of state tourism, one that should be remembered by today’s fans of North Carolina waterways.