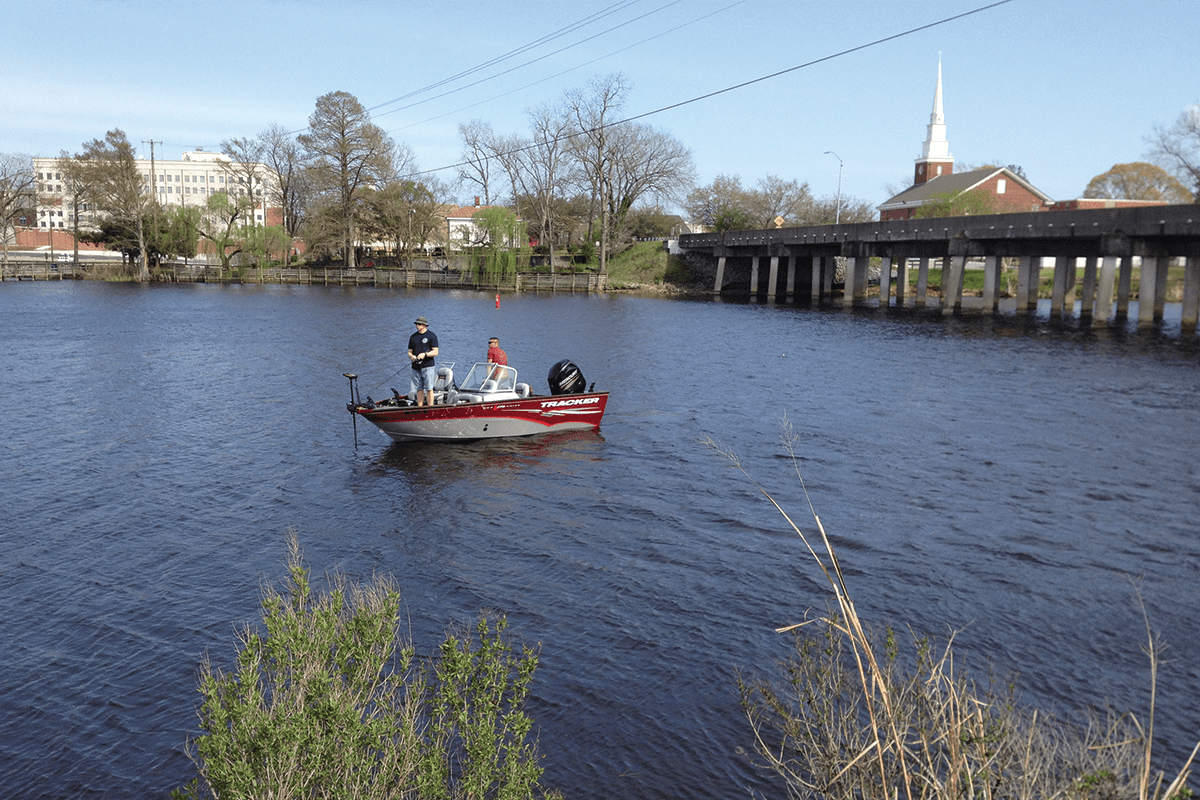

The New River has drastically recovered in the more than 20 years since its waters were first reopened to the public after being closed nearly that same amount of time.

Bacteria levels in the river when it was shut down for recreational and commercial uses from 1980 and 2001 were astronomical. River samples collected during those years contained bacteria levels ranging anywhere from 35,000 to 70,000 organisms per 100 milliliters of water.

Supporter Spotlight

Today, the New River’s waters are close to those of federal drinking water standards, according to weekly sampling results, a success story that got its start when the city shuttered its downtown wastewater treatment plant and Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune stopped discharging from its wastewater facility into the river.

“So, we’ve addressed the bacteria problem in the river,” said Jacksonville Stormwater Manager Pat Donovan-Brandenburg. “What’s left still is the nutrients.”

The city is now in the beginning stages of mapping out how to reduce the amount of nutrients getting into the river, one classified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as nutrient-sensitive.

Jacksonville City Council members recently signed off on the approval of a $400,000 state grant awarded to the stormwater department to develop a New River Nutrient Management Plan, one that will focus on nonpoint sources of nutrient loading into the river.

In other words, stormwater that flows from streets, subdivisions, commercial and industrial areas into the city’s drainage system.

Supporter Spotlight

“All of that stormwater runoff from development carries two things,” Donovan-Brandenburg said. “It still carries bacteria, but that’s from natural sources; birds, deer, raccoon, cats, dogs, those kinds of things. It’s in smaller amounts, way smaller amounts, but it does still carry nutrients in the form of ammonia, phosphates and nitrates.”

While watersheds can manage a certain amount of nutrients, she explained, too many nutrients spur the growth of microscopic organisms that cause algal blooms. These blooms dissolve oxygen in the water and, when oxygen plummets in water, that causes fish kills.

Decomposing fish put more nutrients into a watershed.

It’s a vicious cycle, Donovan-Brandenburg said, but one that the river has, for the most part, evaded the past 10 years.

Last year, there were algal blooms around Sneads Ferry, a small town down river from downtown Jacksonville.

Donovan-Brandenburg attributes one of the causes of that algal bloom to that town’s population increase.

“It’s all tied to development, stormwater runoff,” she said.

In 2008, the city took over its stormwater permitting program because, unlike state employees whose offices are no closer to the city than Wilmington and Raleigh, Jacksonville city employees can be on-site short notice.

Since that year, the city issued more than 150 stormwater commercial and residential subdivision permits.

“And I will tell you we’re increasing,” Donovan-Brandenburg said. “We’ve received more plans this year than we have in the last three. So, we’ve got to do a better job with our (stormwater control measures) and we’ve got to do a better job, not only of building them, but putting them in critical locations where there is a lot of nutrients entering a tributary or the watershed.”

Stormwater control measures, or SCMs, includes things like wet retention ponds and wetlands, bioretention cells, infiltration systems and permeable pavement.

Those need to be maintained and inspected regularly in order for them to work effectively and treat the first 1.5 inches of rainfall by removing stormwater pollutant sediment, bacteria and nutrients.

“The SCMs are to remove the top three pollutants before that water reenters the watershed,” Donovan-Brandenburg said. “The city of Jacksonville, that’s a water quality component. The city of Jacksonville actually goes one step further and does a water quantity component. Instead of making the engineers design to the one-year, 24-hour storm active design to the 10-year, 24-hour storm. That’s not the state rules. That’s the city’s ordinance because we are seeing more and more flooding.”

Why? Because there has been a surge in development, she said. And those additional impervious surfaces – rooftops, driveways, and streets – create more stormwater runoff, which goes into a coastal watershed that’s also being affected by an increasing prevalence of king tides brought on by climate change.

The nutrient management plan will map out which areas of the New River are impaired by chlorophyll a, the predominant type of chlorophyll found in algae.

The New River snakes 50 miles before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean. It’s a slow-moving river, one that flushes once every 60 days, making it particularly vulnerable to nutrient loading.

The nutrient management plan will include developing milestones to track when management measures are implemented, develop criteria to measure progress toward meeting watershed goals, monitoring, and creating an information and educational component.

“This plan will tell us on what areas we need to focus on,” Donovan-Brandenburg said. “Determining those areas will help us identify what areas we need to strategically plan for and implement better and newer SCMs, or retrofit the older SCMs with something more functional. We will be trying to determine the non-point source pollution areas. We’ll be trying to come up with watershed management strategies. We’ve had a lot of people move into our area in the last five years. I don’t think that’s going to stop so we’ve got to do better about what’s coming at us in the future.”