As anybody raised in the South knows — or anyone who’s worked in tobacco, or even driven past a field of it — tobacco blooms are usually pink or white.

Not so much anymore, but once upon a time, tobacco was an invaluable cash crop around here. Tobacco has been an important crop for thousands of years.

Supporter Spotlight

Ever wonder what tobacco looked like 2,000 years ago?

Before we delve into that, think about tobacco seeds. More like dust than what we think of as actual seeds. Tobacco seeds are tiny. Tinier even than mustard seeds.

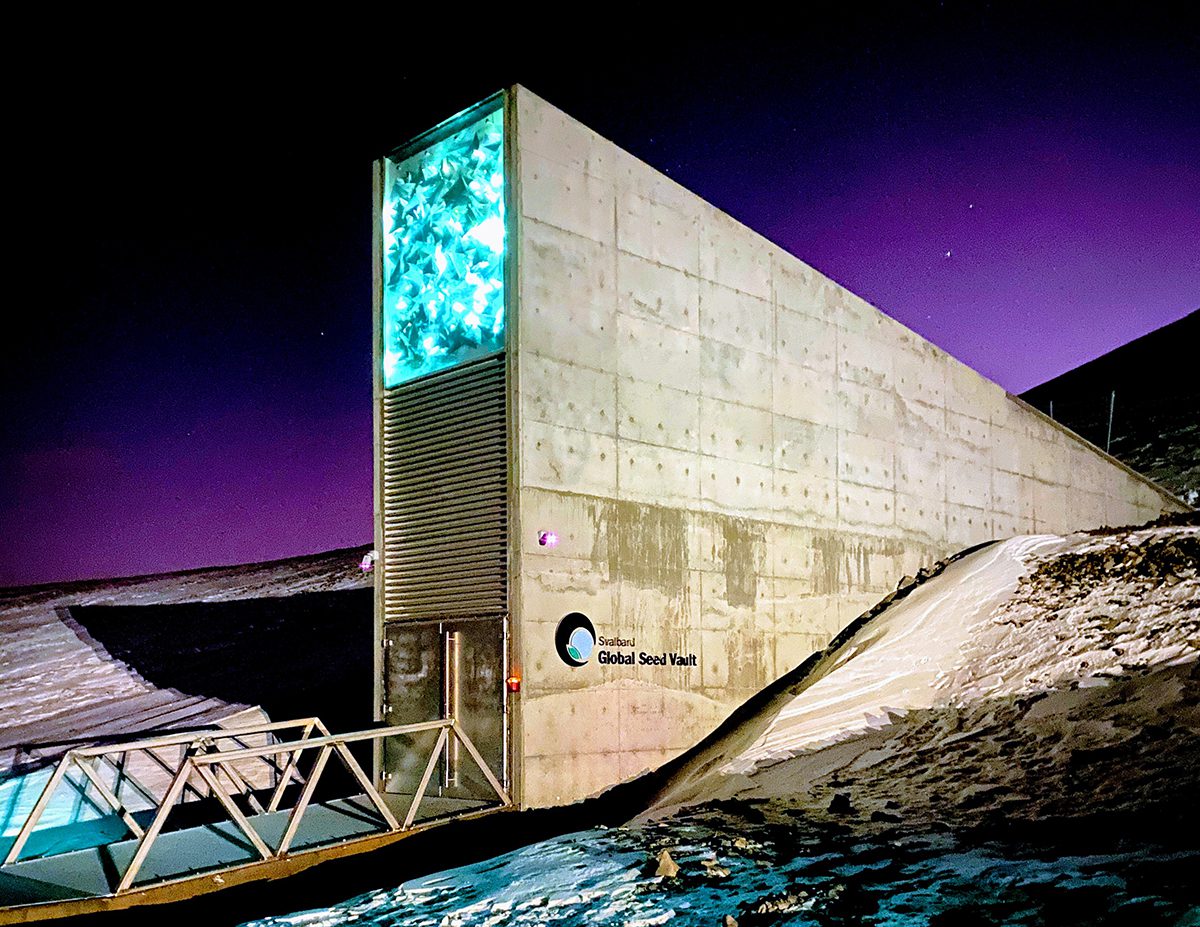

The best way to preserve seeds is to freeze them, because heat and humidity destroy seed viability. Seeds have no idea whether they’ve been frozen for five minutes or 500 years, which is why we have seed vaults like Svalbard, set into the side of a glacial mountain on an archipelago above Norway. Or the Millennium Seed Bank Project in the United Kingdom. There are several in the U.S., as well as others all over the world.

While most of those are climate-controlled fortresses, many individuals also save seeds.

The Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa is the largest nongovernmental seed bank of its kind. The SSE, by growing select varieties of their heirloom and open-pollinated seeds and then saving new seeds, called regenerating, can not only keep the seeds in their bank fresh, they are able to share them with gardeners around the nation. They also send backup seeds to Svalbard.

Supporter Spotlight

Why is it important to save seeds, especially when one can just go to the store or online and order more any time one needs them? Right?

Humans have been saving seeds for as long as there have been farming humans. Over countless centuries different regions have developed varieties that thrive in their specific area. Seeds are also easy to carry, so sharing, or transporting them if one has to move, is fairly effortless.

Oftentimes, seeds were passed down from generation to generation, as treasured heirlooms. As long as families had a few seeds, they were pretty much assured food for the coming seasons. One seed usually produces one plant, but that single plant can produce innumerable seeds.

Seeds are expert hitchhikers. Whether windblown, or carried by water, or in the gullet of some critter, or stuck to the paw or pelt of an animal, seeds do what they’re supposed to do … disperse over as wide an area as possible in order to insure the continuation of their species.

Modern man has engineered seeds to come up all at the same time and to be uniform in growth in order to get the most out of crops. Left alone, seeds germinate randomly, with some sprouting and coming up now, some in a bit, and some quite a bit later. In some cases, even years or decades apart, just in case there’s a late frost, or a flood, or a drought, or a plague of insects, or any one of a hundred other reasons why they might not thrive at that particular time.

Estimates say we, as humans, have lost 75% of our seed diversity in recent times. Why is that important? Instead of having X number of types of … wheat, for instance, we’ve become dependent on just a few types to sustain us. Types that yield more, or are easier to grow, or are just plain better looking. That’s all well and good until something happens to eliminate those few types and suddenly, there’s no way to grow … wheat.

Which is why seed banks are invaluable. Not only do they ensure genetic diversity, they are also a safeguard in case of tragedy, war, wildfires, or any other disaster, man-made or natural.

Heirloom, or open-pollinated, means seeds grown from those plants can be saved and used the following year, and from those seeds you will get the exact fruit or vegetable you grew last year.

Hybrid seeds have different parents, and while you can usually save the seeds and grow them, you will get one or the other of the parents instead of whatever you got the seeds from.

Why choose open-pollinated over hybrid?

Often, hybrid seeds were developed to ensure larger crops, more disease resistance, more insect resistance and longer-bearing seasons.

Open-pollinated, as the name implies, are just that. In order to keep the variety you’re striving for, conditions have to be met or the heirlooms will create their own hybrids, which is where new varieties originate. Other crops in the same family need to be far enough away that the bees and wind won’t cross-pollinate them. The crops have to be grown long enough to let the seeds mature, and then they must be harvested and saved.

Circling back around to the original question about 2,000-year-old tobacco, and why saving seeds is important: Around 20 years ago, a longtime customer came into the independent garden center where I work and have worked for decades. He asked me if I would plant some special seeds for him. I said, “Sure.”

This gentleman went on to explain that a friend of his had been caving in Kentucky. The friend found a pottery jar full of tobacco seeds. The pottery jar was dated to …

… Two. Thousand. Years. Old.

Showing me the pinch of seeds he’d been gifted, my friend offered them to me.

More than willing to try, I didn’t think the seeds would be viable after all that time, and I explained to the gentleman about saving seeds and the odds of them being anything more than old dust. We agreed to plant them and see, with no expectations and only the faintest hope our experiment would work.

To our surprise and delight, the seeds sprouted!

We grew it up, and he harvested both leaves and seeds. This gentleman is big in the Cherokee Nation, and since the cave was on Tribal lands, the tobacco belongs to the Cherokee Nation. My friend gifted it back to the Cherokee, and they use it in their ceremonies all up and down the East Coast!

Instead of being the large-leafed, flue-cured variety we’re used to seeing, the ancient tobacco is a burley type, about 18 inches tall. The blooms are chartreuse and look like little bells.

The Cherokee have a long tradition of saving seeds, as evidenced by the seed in that pottery jar. In fact, in 2020, the Cherokee Nation became the first Indigenous group from North America to send seeds to Svalbard — the seeds of nine heirloom food crops that have been grown by the Cherokee since before the Europeans arrived.