The vote to prohibit balloon releases within Dare County’s unincorporated areas was anticlimactic when its commissioners unanimously voted last week to support the ban.

Southern Shores resident Debbie Swick, the force behind the ban, addressed the board before they took up the vote.

Supporter Spotlight

When Swick began, she pointed to a large, opaque trash bag filled with pieces of balloons propped against the front of the speaker’s podium.

“This bag was collected by five of us over six months. Just five people (and) there’s several hundred balloons in there,” she said. “The National Park Service last year picked up 1,786 balloons along our 70-mile stretch of coastline.”

Now that the rule is in place, it is illegal to release balloons anywhere along the Outer Banks shoreline, from Duck to Hatteras Village.

The county joins its incorporated towns of Duck, Southern Shores, Kitty Hawk, Kill Devil Hills and Nags Head in banning balloon releases. Manteo, which is on Roanoke Island, has yet to prohibited releasing balloons, but the town is in Swick’s sights.

Dare County towns are not the only beach towns in the state that have banned releasing balloons. Similar ordinances are in effect in Wrightsville Beach, Topsail Beach, North Topsail Beach and Surf City. Ten states have also banned balloon releases.

Supporter Spotlight

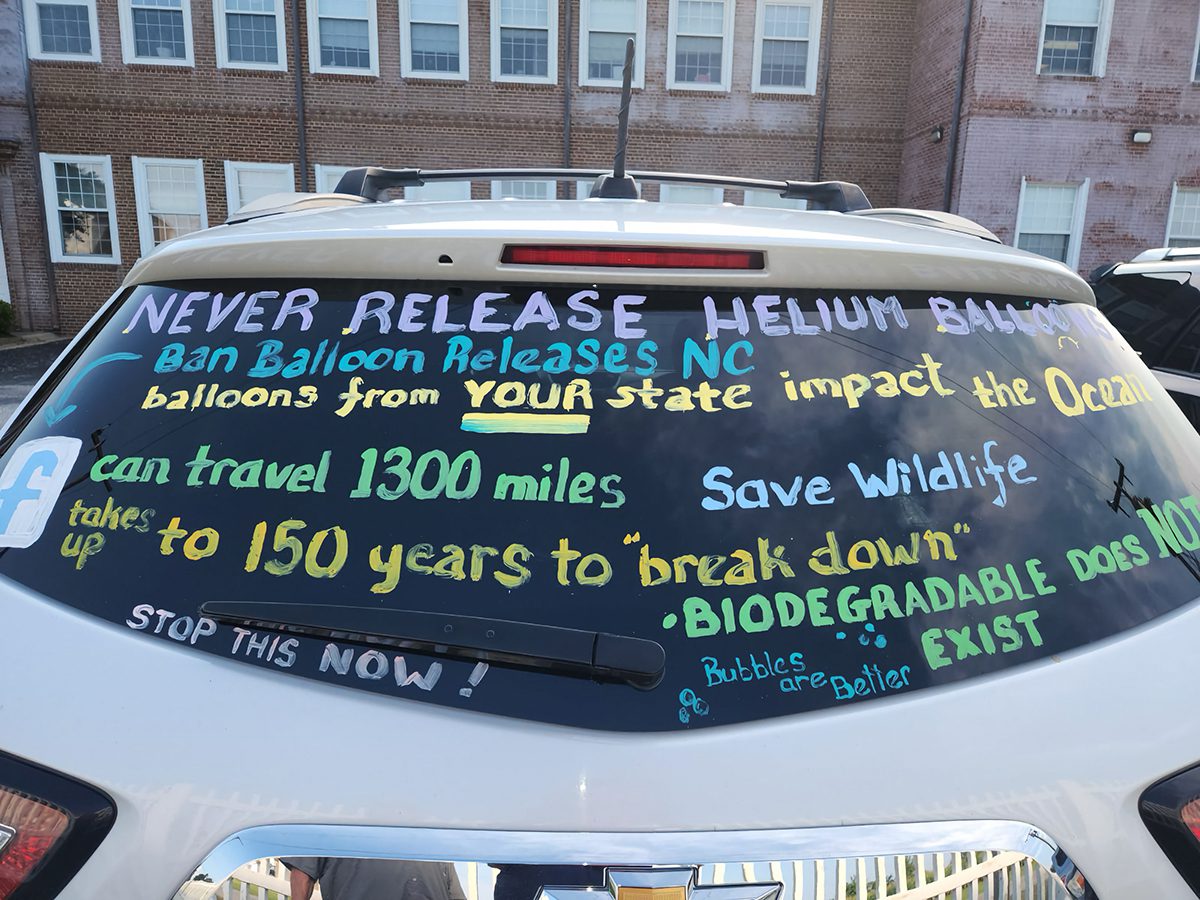

For Swick, a member of Network for Endangered Sea Turtles, or N.E.S.T., based on the Outer Banks, and Outer Banks Marine Mammal Stranding Network, banning balloons has become a crusade, and she has created Ban Balloon Release NC to accomplish her goal.

Although she is a one-person movement now, she said that may change over time.

“I will probably just plug along until I can’t do it by myself and then start looking for more people,” she told Coastal Review.

Coastal North Carolina is just a small part of the problem, she noted.

“You release (the balloon), it’s unretrievable, and it’s going to drift upwards of 1,300 miles from where you release it,” she said, adding the state’s beaches are an ideal location to get the word out about the dangers of balloons in the environment.

“Millions of visitors come from places like Ohio and Kansas and Indiana and Pennsylvania. Balloon releases in their states impact our wildlife and our coastline. So, I’m going to use every opportunity I can to get the word out and educate them,” she said.

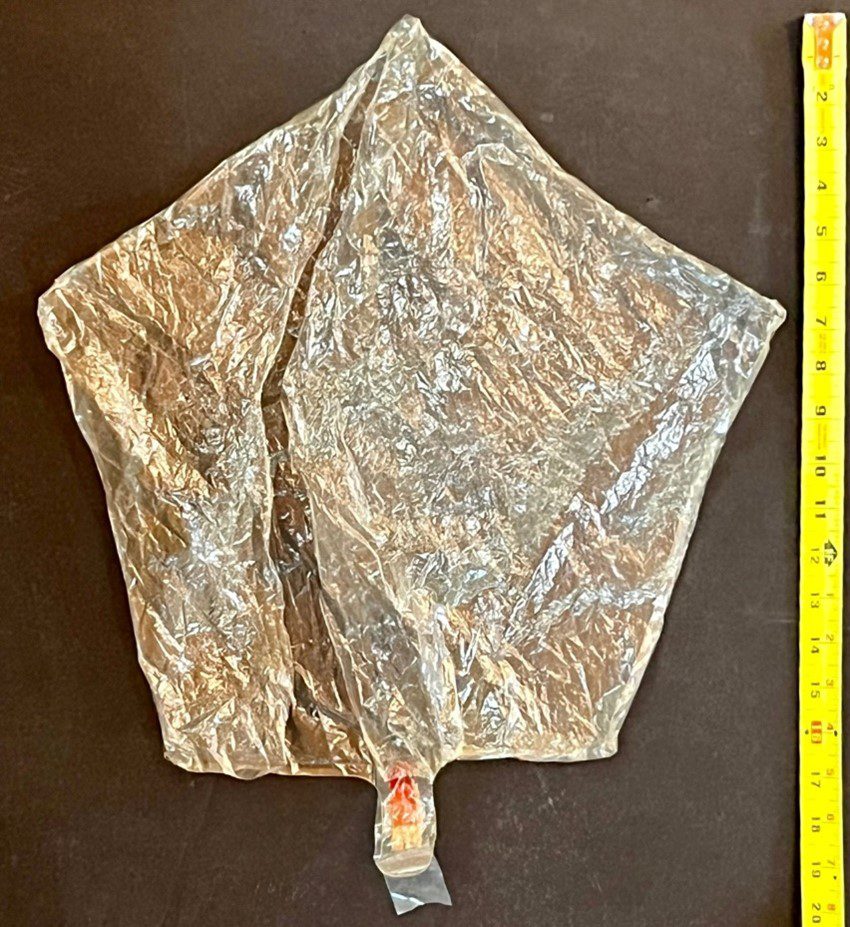

Her fears for wildlife are based in science. One of Swick’s arguments for banning balloon releases is that the balloons do not break down in the environment.

Mylar, which is a polyester, can take hundreds of years to completely break down in the environment. Even latex balloons that are marketed as biodegradable take five years or longer to decompose. The strings used hold balloons in place until they are released are generally not biodegradable.

Balloons in the water look similar to the marine life that are part of whales’ diets. Once in the digestive tract, the balloons are not digested and can cause blockages and death.

Education, understanding are key

Keith Rittmaster, natural sciences curator at the North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort, has been responding to reports of dead and dying whales for a number of years, and he has witnessed firsthand the impact balloons have on marine life.

A Gervais beaked whale that beached off Emerald Isle in 2023 was, to Rittmaster, particularly sad.

“(It was) a nursing calf that had no food in the stomach. No squid parts or fish parts. They had mother’s milk,” he said. “This balloon was blocking the entrance to the stomach so no milk could pass. I had to use my imagination to figure out what was going on. I can’t imagine it was anything but this was the first bite that this whale took.”

Whales are not the only marine species affected by the balloons that have landed at sea. Seabirds and sea turtles regularly become entangled in the lines and sea turtles, like whales, will try to eat the balloons.

Rittmaster, whose area of expertise is marine mammals, said that researchers are seeing an unexplained phenomenon regarding whales.

“What we’re learning, which is kind of an ‘oh, wow!’ to me is, we’re finding more plastic balloons all the time in deep-diving whales rather than shallow-diving whales,” he said.

He then sounded a cautionary note about the problem’s pervasiveness.

“It’s going to get worse even if we ended it today,” he said. “If, for some miracle, we could end the releasing of balloons today — I feel pretty confident since these plastics last hundreds of years — this problem is going to continue to get worse, not just the balloons themselves, but the plastic and nylon strings that they are tied to.”

Like Swick, Rittmaster is resolute in calling for action.

“There’s a lot of things that are terrifying us that we can’t even conceive how to solve in generations. This is something we can solve,” he said.

The challenge is often frustrating.

After the city of Greenville voted 4-3 in the fall of 2023 against an ordinance that would ban balloon releases, Rittmaster led some workshops about what happens when a balloon is released.

“A politician was there,” he recalled. “And I gave the presentation and she said, ‘Can we just release the balloons inland but not release them along the coast?’ This isn’t a bad person. She doesn’t really understand, and that highlighted to me what we’re up against.”

Swick believes education is the key, and with that knowledge will come a better understanding of the world around us and perhaps a hope for future generations.

“This is just such small potatoes, so it gets pushed on the back burner…This is one of those things, it’s not going to go away until we decide to make a change,” she said. “It’s going to take a lot of educating but my hope is that the generations of children that are coming up, (that they) learn a valuable lesson and take that with them as they grow into adulthood and raise children.”