RALEIGH — While the need to manage water in the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula is a centuries-old endeavor, rising sea levels and increasing impacts from climate change have been overwhelming prior flood-mitigation methods in the sprawling lowlands within the nation’s second-largest estuarine system.

“The Scuppernong River Basin in the heart of the Albemarle-Pamlico region in eastern North Carolina faces significant water management challenges due to factors such as changing precipitation patterns, manipulated land-use, and increasing water demand,” the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, or APNEP, explained in a recent newsletter.

Supporter Spotlight

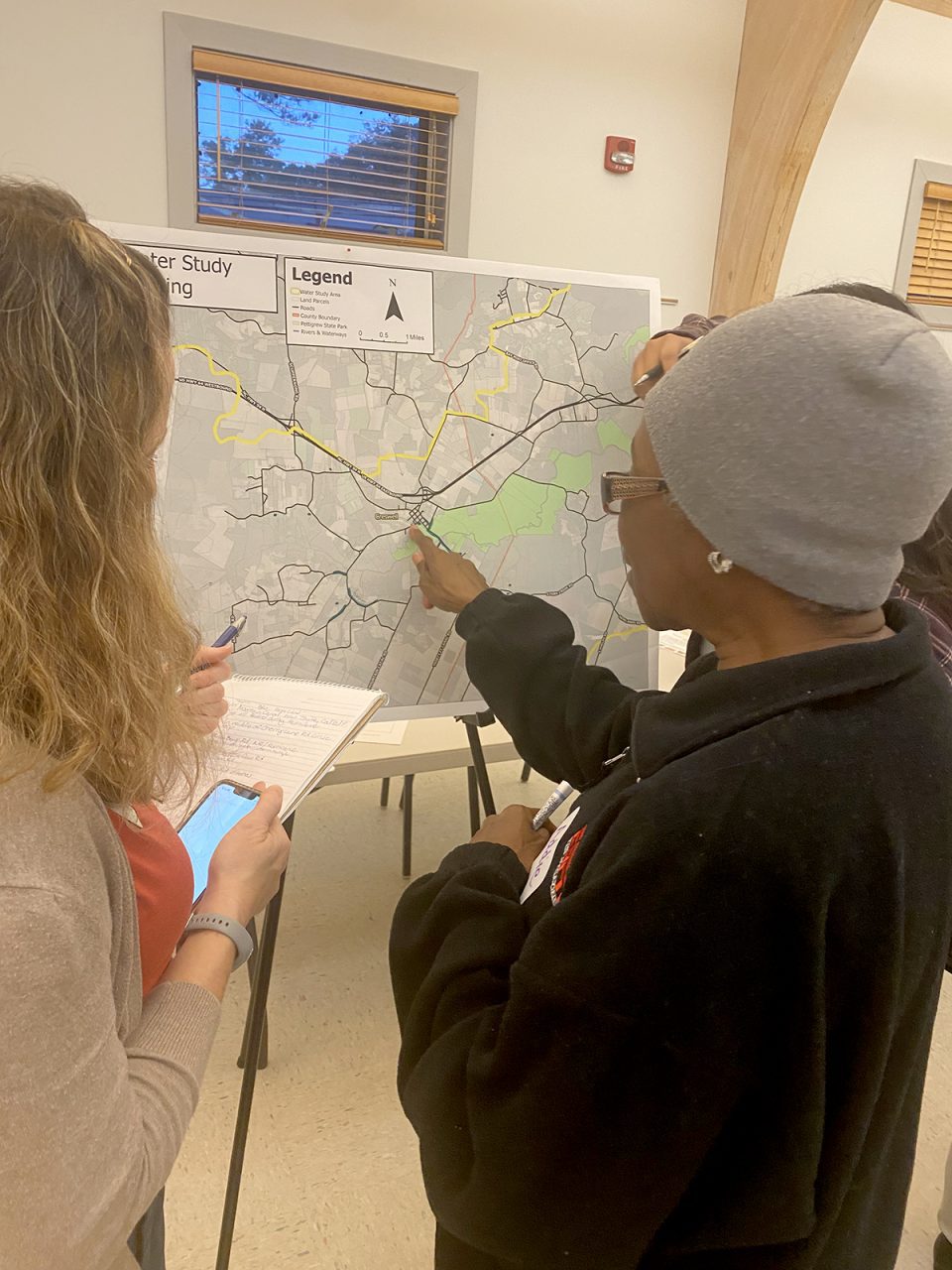

Piecemeal efforts to address the challenges are now starting to be stitched together in a regional approach, spurred by a $50,000 grant for community engagement from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office for Coastal Management Digital Coast and the National Estuarine Research Reserve Association, followed by a $200,000 grant from the state Department of Environmental Quality and a $200,000 in-kind matching grant for the recently launched Scuppernong Water Management Study.

“The goal was to have that community engagement and local input shape the study and inform, so it’s not just a desktop exercise, an engineering exercise,” Stacey Feken, APNEP project manager, recently told Coastal Review.

Origins of the study go back to plans to update a water-management plan for Lake Phelps, which had not been updated since the early 1980s. Pettigrew State Park was trying to figure out how to do the update, Feken recalled and, in the process, park officials decided that since water knew no boundaries, it would make sense to look at its management on a regional basis.

“We wanted to do this in collaboration with partners in the area, other land-conservation managers and the landowners and the communities,” she said, recounting what Pettigrew officials had conveyed.

Pettigrew had approached APNEP about five years ago for help, Feken said, and the partnership has since taken the helm in developing the study.

Supporter Spotlight

“They brought us in to serve as a neutral, science-based partner,” she said. “So, we’re serving as a convener, doing everything from technical assistance and grant writing to the community engagement associated with the study.”

Grant applications for state parks were able to be broadened beyond park boundaries, and a funding request was made for the planning and engineering feasibility study through DEQ’s Water Resources Division.

Although the focus was initially on Washington County, where most of the 5,830-acre Pettigrew State Park and Lake Phelps are located, it was soon discovered that nearby local governments in Tyrrell County and organizations representing the counties and communities had been long asking for state assistance to cope with flooding issues.

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the planning. Once the crisis passed, APNEP contacted the Albemarle Commission, a regional government council, to help in the effort. Other partners that have joined are Buckridge Coastal Reserve, Washington County, Tyrrell County, Washington County Soil and Water, Tyrrell County Soil and Water, Pettigrew State Park, Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, and the North Carolina State University Cooperative Extension.

A steering committee comprised of local stakeholders was created to serve as a liaison to the communities, ensure effectiveness and to advise the engagement team, which, in addition to APNEP, includes representatives from the North Carolina Coastal Reserve, North Carolina Sea Grant and The Nature Conservancy.

Cary-based contractor Kris Bass Engineering, through models, mapping and other tools, is to identify flood-prone areas, enhance understanding of water movement throughout the region and identify potential solutions to flooding.

“The study will help inform development of a comprehensive plan to address water management issues on both private and public lands inter-connected by an extensive drainage network on the northern portion of the Albemarle-Pamlico Peninsula,” the APNEP newsletter said.

As part of the comprehensive study, organizers are asking the public to share observations of how flooding impacts these communities by Jan. 15 through an online survey.

Results from the study could be used to inform other more localized studies, such as the Pettigrew State Park water management plan update, Feken said.

“My understanding with the engineers, they’re developing the modeling for the study so that it can be easily replicated in other areas of the region,” she said.

Feken said that she expects that another study would be done in the near future for the southern portion of the Albemarle-Pamlico region, which includes Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge in Hyde County and the Pungo River area.

Located within some of the most rural and economically distressed counties in the state, communities in the Albemarle-Pamlico region have often felt forgotten as surrounding beach communities and urban areas with fat tax bases were thriving.

But the uniqueness and ecological importance of the region have lately brought remarkable amounts of attention from conservation groups, nonprofits and government agencies, as reflected in efforts of groups including the North Carolina’s Natural and Working Lands initiative, North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency, Coastal Resilience Community of Practice and the Audubon Society’s community-driven projects, among others.

The ecosystem is extraordinarily rich, and situated just feet above sea level, vulnerable, with pocosin peatlands, forests, sounds, bays and lakes that provide habitat for wildlife that includes endangered red wolves, black bears and numerous other mammals, plus thousands of waterfowl and other birds, as well as countless amphibians, fish and reptiles.

“It’s just such an amazing landscape in different ways,” Feken said.