There are wild cranberries along the highway, U.S. 264, as it passes Stumpy Point in Dare County heading west to Engelhard.

It is a small patch, according to Bob Glennon, retired Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge planner, and largely inaccessible without hip boots and a guide to find them.

Supporter Spotlight

“The cranberries are on the part of the refuge with the deepest muck soil,” he wrote in an email. “The site has very deep organic soil that will not support a person’s weight.”

The cranberries that exist in the pocosin are Vaccinium macrocarpon, the same botanical name given to the cranberry that has become a part of Thanksgiving and holiday traditions. They’re smaller than their cultivar cousins, but it’s the same cranberry.

The first European settlers did not mention cranberries, but Glennon is confident the plants were there.

“Because they are present where there is very deep organic soil, I would guess that they have been there for centuries, just as other plant communities in extreme environmental conditions … have existed for centuries,” he wrote.

What may be one of the most remarkable features of where the cranberries are found is that the area does not seem to have changed much at all.

Supporter Spotlight

“Stumpy Pointers on Excursion” the headline reads in the Nov. 13, 1914, Elizabeth City Advance. The excursion — a cranberry picking expedition that included crossing open water and hiking through pocosin — is described in detail.

“After a twenty minute row across the lake and a hundreds yard hike through dense woods, the party came to an open savanna which must needs be crossed before the cranberries were reached,” the paper reported.

That description is remarkably similar to how Michael Schafale, North Carolina Natural Heritage Program terrestrial ecologist, got to the site.

“That 1914 description really fits,” he wrote in an email. “Lake Wirth, near Stumpy Point, is on the edge of that low pocosin. I went in that way once, walking around the lake rather than rowing across it. It is not too far to low pocosin that way, though the ‘hike through dense woods’ and ‘savanna’ is understated.”

It does not appear as though the earliest Colonists left a record of the fruit, but North Carolina newspapers’ reporting on the crop dates back to the 19th century.

The headline on page two of the Oct. 30, 1883, Elizabeth City Economist simply reads “Cranberries” and tells readers that the Massachusetts cranberry harvest was not very good in 1883 and “that the price will probably be higher than any time in recent years.”

The observation was followed by advice for Dare County residents.

“We hope it will be appreciated by our friends at East Lake and other cranberry sections of Dare County. The dwellers in Dare County by the side of the wild cranberry ponds have no idea of the mine of wealth around them, and which they can so easily gather,” the paper noted.

Knowledge of the potential wealth of the bogs seemed to come and go. If the East Lake cranberries were well enough known in Elizabeth City in 1883 to note their abundance, by the 1930s they seem to have been forgotten.

A July 1, 1938, Dare County Times full page spread extolling the wonders of Dare County as the first show of the second year of “The Lost Colony” theatrical production neared, seems to indicate the existence of the cranberries has just been discovered.

The article describes the bogs with what may be hyperbole, writing that what exists between Alligator River and Stumpy Point “surprisingly enough, constitute the greatest cranberry bog in America.”

The next paragraph then describes how the cranberries had just been discovered.

“Nobody knew very much about the cranberry bog until they began to excavate a road through the unexplored jungle … that lie between the Croatan (Sound) and Alligator (River).”

That road today is U.S. Highway 264, but according to a History of Stumpy Point published in NCGenWeb Project, that road was created in the 1920s. The NCGenWeb Project is part of the national USGenWeb Project and a volunteer-collected genealogical and historical content repository for each of state’s 100 counties.

“One of the biggest milestones in the history of Stumpy Point was the creation of the roads connecting the town to Engelhard and Manns Harbor. The first was the road to Engelhard in 1926, built for Dare County by the H. C. Lawrence Dredging Company,” Harold Lee Wise, the story’s author wrote.

The cranberries seem to have been a good quality crop. Theodore Meekins, a Dare County resident, entered the cranberries in a statewide horticulture competition in 1908 and took home a bronze medal. In November 1939, according to the Dare County Times, Theodore Meekins “suggested that cranberries be cultivated on the Dare County Mainland.”

What is not clear is the extent of the commercial cultivation of the cranberries.

Alan Weakley, director of the University of North Carolina Herbarium at the North Carolina Botanical Garden, responded in an email that if a commercial harvest did exist, it was probably taking advantage of natural conditions.

“I’m quite strongly inclined to think this was at most commercial exploitation of a natural local population,” he noted. “Maybe they manipulated the habitat some. But I find it really hard to believe that Dare County folks would have the idea of planting cranberries in pocosin habitats in Dare County, where they actually grow naturally and natively, and acquired plants or seeds and set them out.”

Newspaper accounts would seem to confirm Weakley’s opinion. By 1952, according to a Coastland Times article from Dec. 12 of that year, there was no commercial harvest of cranberries in Dare County.

“There was a time when gathering wild cranberries was a profitable venture for persons living in the bogland of the Dare Coast,” the paper reported.

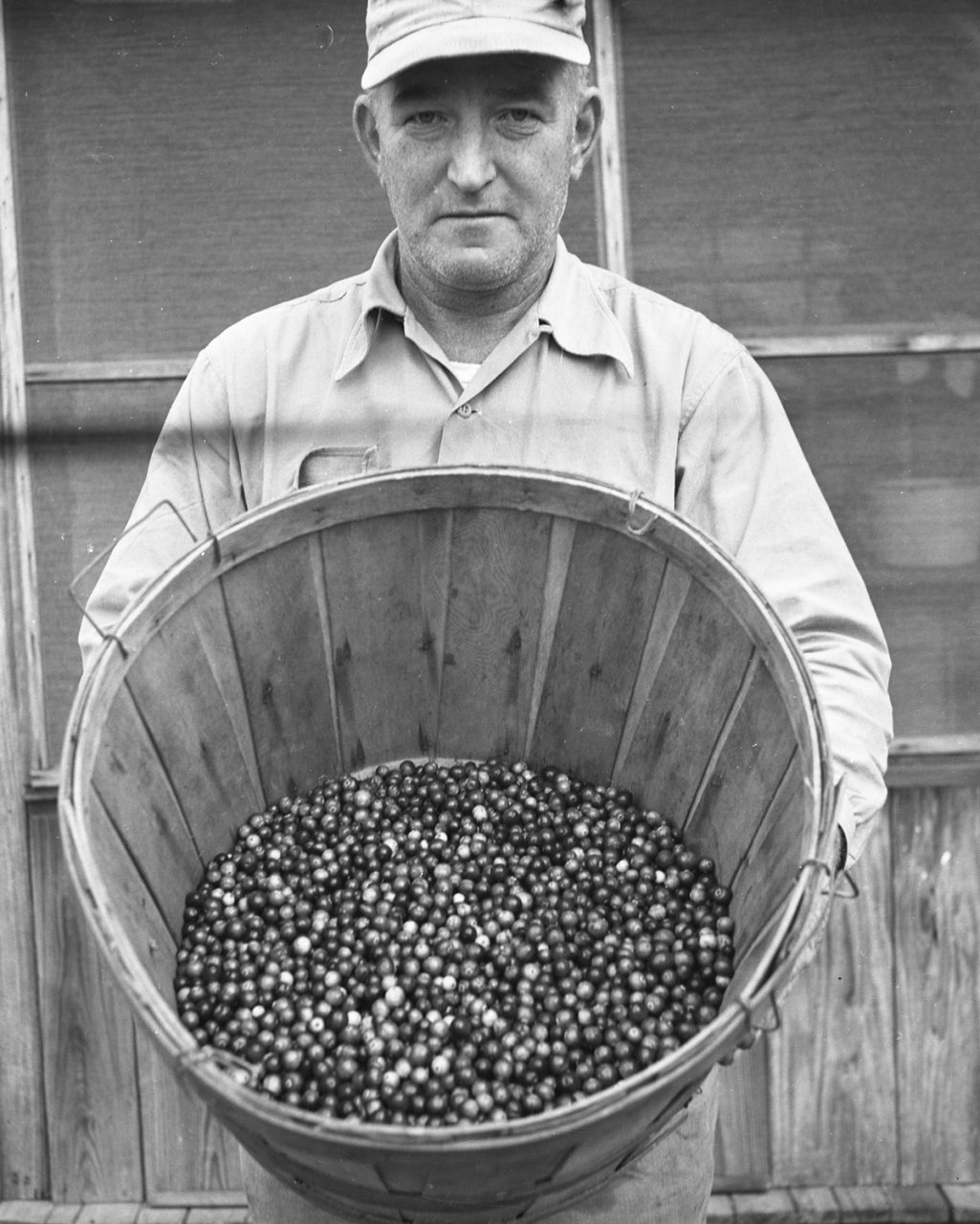

In that same article, the harvest of the cranberries is then described in detail.

“Thomas Hunter Midgett is one person who still gathers wild cranberries in the same method as his parents and grandparents harvested them from the boglands many years ago,” the article noted. “The wooden scoop he uses is one his grandfather used.”

Charles Brantley “Aycock” Brown (1904-1984) was an Outer Banks resident and journalist.

Coastal Review will not publish Thursday and Friday in observance of the Thanksgiving holiday.