Despite being recently ranked as the state with the seventh-worst feral hog problem in the country, most North Carolinians aren’t likely to spot them feasting on crops in the Piedmont, eating away mussel mounds in coastal salt marshes, or devouring rare, native species of small animals in the mountains.

Compiled data in a recent report released by Captain Experiences, an online platform for hunting and fishing excursions, places North Carolina among the top 10 states with the largest feral hog populations.

Supporter Spotlight

In that account, the number of feral hog reports in North Carolina topped 655.

But those numbers are well below the wild boar count tallied in the state this year by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Between Jan. 1 and Nov. 19, 1,612 feral swine were killed and subsequently sampled to monitor for disease.

The reality is, state officials say, there is not a solid estimate of how many of these free-roaming, highly intelligent, disease-carrying animals are in the state.

And there is no way for state officials to monitor feral swine populations.

Supporter Spotlight

Not yet anyway.

Elusive and evasive

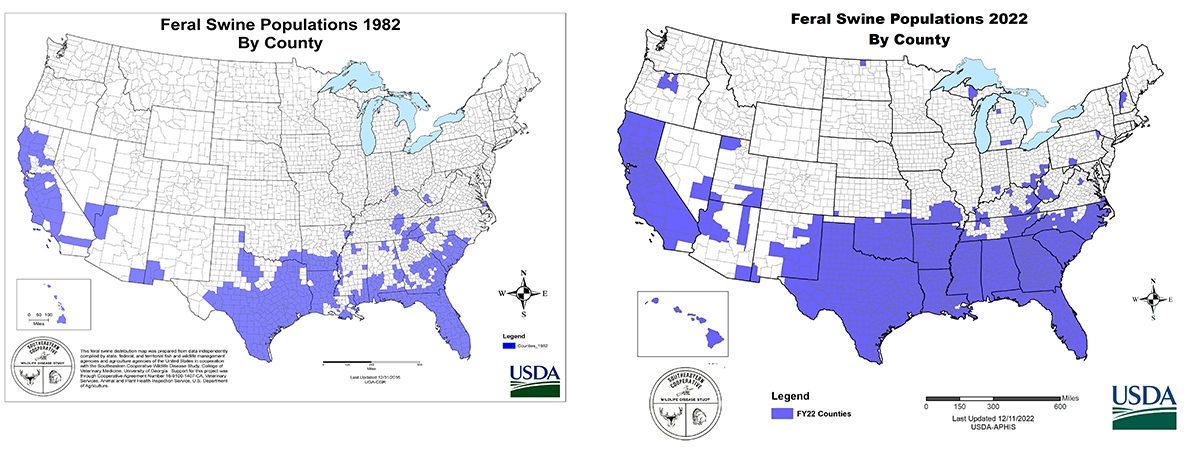

The Southeast has long had the biggest, most expensive, and most historic feral swine populations in the country.

North Carolina has had free-ranging populations of swine since the early 1500s, when Spanish conquistadors released their version of domestic pigs into the wild, said Falyn Owens, state Wildlife Resources Commission extension wildlife biologist.

“That’s not to say that the problem hasn’t gotten worse,” she said.

And officials simply do not have a good idea of how widespread the population of feral swine are in the state.

“We don’t in North Carolina have a good estimate of the population of feral swine across the state because it’s a really, really hard number to pin down,” Owens said.

In no area of the state is this challenge more prevalent than the coastal region.

The reason for that is twofold. There are fewer people who reside in remote coastal areas where wild hogs are likely live and leave evidence of their destruction.

In addition, a particular type of hunting popular in the coastal region keeps wild hogs on the move twice as frequently in coastal areas as compared to the Piedmont or mountains, said Wildlife-Livestock Health Director Aaron Loucks with the state agriculture department’s veterinary division.

“When you have dog hunting around feral swine and you’re trying to do any population mapping at all, or any disease monitoring at all, it becomes extremely difficult because those pigs are being moved around so much,” he said. “So, the ability to count populations of pigs on the coast, specifically North Carolina, becomes very difficult with that aspect of their management.”

That’s bad not only for property owners, but salt marshes, according to the results of a 2021 study that found destruction caused by feral hogs in salt marshes affect a marsh’s ability to recover from drought and sea level rise.

Feral hogs are omnivores, feasting on “pretty much anything that is organic,” Owens said.

They forage for everything from invertebrates to nuts, berries and seeds, though they’re just as happy eating small animals and decaying flesh off animal carcasses.

Their hair-covered bodies can weigh hundreds of pounds, but typically weigh between 100 and 200 pounds.

Feral hogs, though very capable of defending themselves if cornered, are averse to coming too close to humans, Owens said.

“Usually, if there’s pigs around, you’re not even going to see them or you’re going to see them on the other side of a field, and you’re just going to see the tail-end of them as they’re running away. They do not want to interact with us,” she said.

And they are “disturbingly intelligent,” Loucks said, adding that the animals are keenly aware when something happens within their social group.

Their innate aversion to risk keeps them on high alert. Unlike other animals who may, for example, stop to nibble on a bait pile of corn, feral hogs appear to suspect a human ploy.

Population and disease management

This year, feral hogs have caused more than $1 million in damage to crops and farms in the state, according to Loucks.

“That damage number is significant because a biologist physically walked that land with the damage,” he said in an email. “It was recorded and verified on the ground alongside a farmer.”

Two of the crops suffering the most destruction have been soy and corn. In some cases, Loucks said, farmers this year have quit growing one or both of those crops altogether.

Not only are feral swine destructive to agriculture, waterways and coastal resilience, they can carry a host of diseases that can spread to other animals, including livestock.

When that happens, it can have devastating effects on the livestock market and its producers, costing billions of dollars in losses nationwide.

Females can birth up to five litters every two years. Each litter typically includes between four and six piglets, though some females can give birth to up to 12 piglets, Owens said.

Killing them off one-by-one isn’t going to control their populations.

“There’s never been a country or a state ever that has hunted their way out of the problem,” Loucks said. “You might kill a few, but the rest of them are going to disperse on your neighbor’s land, cause damage for a few years, and then come back, and now they’re significantly more educated so it makes this problem just exponentially harder to control.”

Instead, agencies have turned to the use of corral traps, which can be set up to capture whole social groups of feral swine. Once captured, the hogs are shot.

It is illegal in North Carolina to release swine into the wild.

Yet feral hogs continue to be transported into the state illegally for sport hunting, a lucrative business.

These so-called illegal sport translocations put “a lot of farms at risk that wouldn’t necessarily be in that spot,” Loucks said.

But there is good news.

“The need is exponentially increasing every year to handle feral swine as a state, and that need will translate to less and less illegal sport translocations,” Loucks said.

The agriculture department is currently working on way to monitor feral swine populations through a mapping system, one that will identify populations with a minimum of 100 breeding females.

About 20% of the mapping has been completed.

“The overall consensus is: We have a lot of pigs in less places than we thought,” Loucks said. “We thought it was this widespread, 100-county problem, and it turns out it’s really not. It’s a few focal areas.”

At the beginning of this year, the state changed how it operates a program aimed at helping property owners capture feral pigs on their property by bolstering education and communication with landowners.

What began as a corral-trapping program for six counties has expanded statewide.

The state works with landowners to write out formal management plans and sets up corral traps for property owners having a problem with feral hogs on their land. All that is asked of a property owner is to provide corn to place inside a trap.

“We have traps set up in 15 counties that are active and another 33 counties with population monitoring efforts,” Loucks said in an email. “More traps have been purchased, gone out to private lands, and reduced the population of feral swine in those high-risk areas.”

And it doesn’t stop at the state level. Counties and individual states are communicating more often and more than ever following the 2020 shutdown resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“All of the entities doing serious disease work around the world started sharing what’s working, and more importantly, what is not working in terms of their disease monitoring,” Loucks said. “All of our management has to be disease-focused so we can be prepared. At this point we have a very much winning formula and it’s because everybody’s involved.”