First in a series investigating why, after years of consistent seasons for inland, joint and coastal waters, recreational anglers found themselves negotiating different flounder and mullet rules in 2023.

Up until recently, the North Carolina Marine Fisheries Commission, which manages coastal waters, and North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, which manages inland waters, appeared to have a system in place for the shared responsibility of what’s known as joint waters.

Supporter Spotlight

However, since forming a Joint Committee on Delineation of Fishing Waters in late 2018, there’s been a paper trail of mounting disagreements between the two on managing the area between inland and coastal waters.

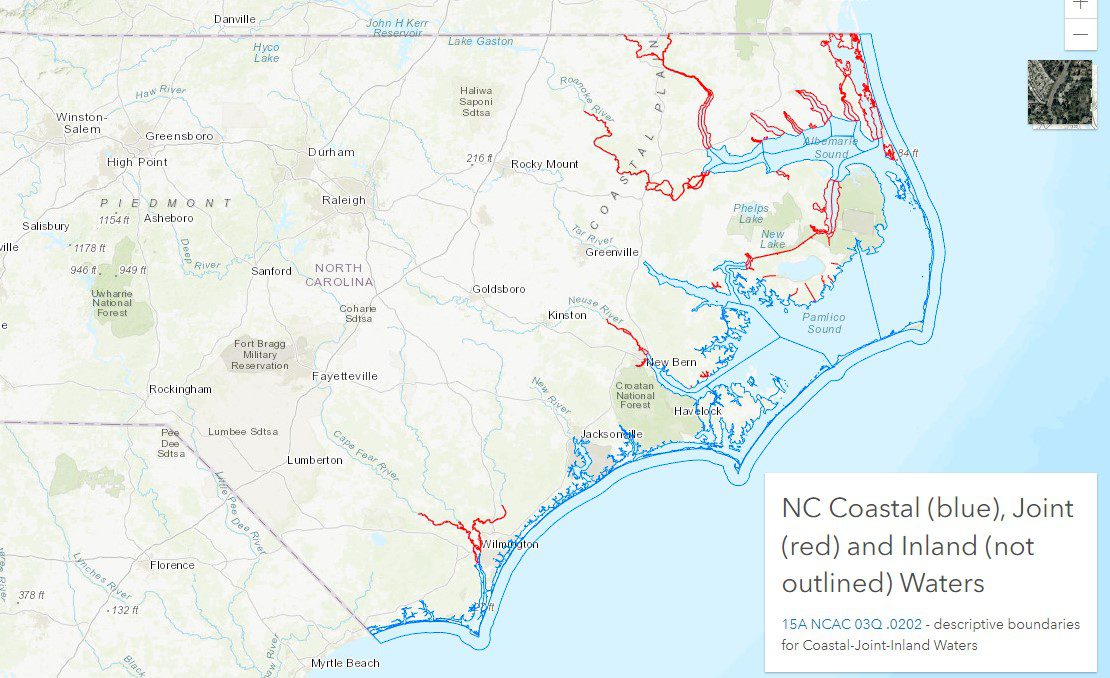

Division of Marine Fisheries Public Information Officer Patricia Smith told Coastal Review that the joint committee was formed to determine boundaries defining inland, coastal and joint fishing waters under a statutorily mandated periodic review of rules. Delegates of the two commissions met periodically, but the discussions ended without consensus.

The conflict came to a head last year because the two were unable to agree on changes to joint water rules, which require approval by both commissions before they expired. Because of the dispute, the governor’s office intervened in February 2022 and directed both to approve existing joint rules as written, according to past meeting minutes of both agencies.

Both agencies readopted the joint boundary rules without change later that year but continue to strive for consensus, Smith said.

A Wildlife Resources Commission’s committee approved that summer a memorandum of agreement that included maps with proposed boundaries for coastal and inland waters. The Marine Fisheries Commission discussed the agreement, maps and other aspects of this issue at its November 2022 meeting, but did not vote on the agreement, she said.

Supporter Spotlight

Friction appears

The friction between the two agencies became evident earlier this summer.

For the first time in years, recreational flounder seasons for inland waters and coastal waters didn’t overlap, meaning rules for joint waters didn’t either.

Flounder season for Wildlife Resources Commission in inland waters was the first two weeks of September with a limit of four fish per day, and for Marine Fisheries, the second two weeks of September in coastal waters with a limit of one fish per day.

Mullet seasons are inconsistent as well.

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission officials said in a statement provided Thursday that, “there is no closed season for the harvest of Striped Mullet and White Mullet in Inland Fishing Waters by any lawful method or in Joint Fishing Waters by hook and line. The daily creel limit is 200 mullet in combination with no minimum size limit.”

As with flounder, the statement continued, “WRC enforcement officers will enforce our season and creel rules, and, for questions about how marine patrol plans to enforce the proclamation, please contact NCDMF,” or the Division of Marine Fisheries.

Commission Inland Fisheries Division Chief Christian Waters explained in an email that its current mullet rule applies to all legal gears used in inland fishing waters and for joint fishing waters when taken by hook and line.

Division of Marine Fisheries Director Kathy Rawls declared by proclamation that it is unlawful to possess mullet in North Carolina coastal and joint fishing waters for recreational fishers and for commercial purposes such as possessing, selling or offering for sale, in waters north of the Emerald Isle bridge as of Nov. 7, and as of Nov. 10, south of the bridge. The closure expected to end Dec. 31 is estimated to result in a 20% reduction in harvest.

Marine Fisheries Commission officials said in May when they approved the measures to address overfishing of striped mullet in state waters that the most recent striped mullet stock assessment indicated that the stock is overfished and that overfishing is occurring.

North Carolina Fisheries Association Executive Director Glenn Skinner told Coastal Review that he is concerned about the consequences. Both agencies claim authority over joint waters, meaning anglers may or may not be allowed to possess mullet in joint waters, depending on which agency’s officer they encounter.

To make matters worse, Division of Marine Fisheries officials have given dealers, fish houses and bait shops until Nov. 18 to dispose of any mullet they have at their place of business, even though they were caught and purchased legally, prior to the closure, Skinner said.

“We believe this represents an illegal take of property by the State, violating both our State and Federal Constitutions,” he said.

Flounder in joint waters

The Wildlife Resources Commission established in February 2022 its 2023 flounder season set for Sept. 1-14 for inland fishing waters and when using hook-and-line gear in joint fishing waters.

The Marine Fisheries Division announced June 28 that its 2023 recreational flounder season for coastal and joint fishing waters would be Sept. 15-30, with a possession limit of one flounder per person, per day.

Both agencies in late August released statements explaining their decisions regarding the flounder seasons.

Waters said in the Aug. 30 statement that when the commission adopted in February 2022 its current rule for flounder, it “mirrored the recreational season, size, and creel limits established by proclamation of the Division of Marine Fisheries director for coastal fishing waters.”

He continued that it was not until June 28 that the commission learned through a Division of Marine Fisheries news release of its intent for this year’s season and creel limit.

“You may ask, ‘Why can’t the Wildlife Commission change or simply not implement its rule?’ Legally that is not an option, given the Wildlife Commission does not have proclamation authority like the Division of Marine Fisheries,” he said. “Our agency cannot modify a rule or suspend a rule without going through the rulemaking process, which includes opportunity for public input. Had we been informed of Marine Fisheries’ plans sooner, we could have attempted to address the discrepancies through temporary rulemaking. However, two months is not enough time to complete the rulemaking process as outlined in the Administrative Procedures Act.”

Division of Marine Fisheries officials said in an Aug. 31 announcement that the flounder management measures “are science-based and required by law to ensure the long-term viability of the State’s commercially and recreationally significant species. Ending overfishing and rebuilding overfished stocks within the timeline set out in the Fishery Management Plans is essential for the conservation of these fish for the enjoyment of current and future North Carolinians.”

Additionally, the Division of Marine Fisheries rule prohibits the possession or transport of flounder through coastal or joint fishing waters when those waters are closed to flounder harvest, regardless of where the species was taken.

The inconsistent flounder seasons led to four warnings from Marine Patrol in the first two weeks of September for unlawfully possessing or transporting flounder through coastal waters.

“These warnings were a direct result of the Wildlife Resources Commission’s opening the flounder season in inland waters and the fisherman transporting outside of those waters,” a division representative said.

In response to these warnings, Wildlife Resources Commission Executive Director Cameron Ingram wrote a letter Sept. 8 addressed to Rawls, stating he was appalled when he was informed marine fisheries officers had been directed to take enforcement actions against anglers for fishing or transporting fish in joint waters during an open season that was adopted in 2022, approved by the Rules Review Commission, subjected to legislative review, and codified months before the division’s proclamation.

He said the warning citations issued by Marine Patrol officers for “transport fish not in compliance w/ body of water” were issued to anglers in joint waters on Wildlife Resources Commission ramps and these “actions are completely unacceptable, unprofessional, and likely unlawful.” He said that Wildlife Resources Commission officers would not be taking similar criminal actions against the angling public during the Marine Fisheries Commission season announced in joint waters starting Sept. 15.

Division’s view

Rawls, during a Marine Fisheries Commission meeting Aug. 25, explained that although the Wildlife Resources Commission has authority in inland waters, their rule conflicts with the requirements of Amendment 3 to the Flounder Fishery Management Plan, therefore causing confusion to the regulated public. Amendment 3 maintains a 72% reduction across the fisheries, according to the division.

“And more importantly, because these regulations are a divergent from the current Marine Fisheries Commission regulations, which in contrast are based on data, sound science, and management and in accordance with sustainable harvest requirements, which are outlined in state law, this impacts the Marine Fisheries Commission and the Division of Marine Fisheries ability to meet the objectives of the Flounder Management Plan,” she continued.

Rawls explained that the Wildlife Resources Commission “now believes that they have sole authority over all hook and line fishing in joint waters despite the fact that they have not exercised that authority since the joint rules were created decades ago.”

The Wildlife Resources Commission executive director had called her earlier in the week to let her know that they would be announcing their authority over hook and line in joint waters to the public “and that he hoped we could be on the same page about this interpretation,” she continued.

“Certainly, not to his surprise, I let him know that we are absolutely not on the same page and that the Division of Marine Fisheries nor the Marine Fisheries Commission agree with this interpretation. I let him know and I also want to let this commission know that the Division of Marine Fisheries will continue to implement and enforce the rules and regulations of the marine fisheries commission as we always have.”

Rawls referred to the governor’s office having directed in 2022 both agencies to readopt the joint rules as is and the Division of Marine Fisheries has been operating as is — not only the rule text but also the way the rules have been implemented and enforced for decades.

“It has become abundantly clear with the Wildlife Resources commission’s recent actions that their focus is on jurisdictional boundaries with a total disregard for the condition of the flounder stock,” she said.

Wildlife Resources’ perspective

During a Wildlife Resources Commission committee meeting Aug. 24, Waters, while discussing the two flounder seasons, told the board that it has regulatory authority over inland waters and hook and line in joint waters, but with joint waters, “there’s a little more nuance.”

State law says that “joint waters are deemed coastal waters from the standpoint of laws and regulations administered by the Department,” which is the Department of Environmental Quality and its Division of Marine Fisheries, “and are deemed inland waters from the standpoint of laws or regulations administered by the Wildlife Resources Commission,” Waters read.

“‘The Marine Fisheries Commission and the Wildlife Resources Commission may make joint regulations governing the responsibilities of each agency and modifying the applicability of licensing and other regulatory provisions as may be necessary for the rational and compatible management of marine and estuarine and wildlife resources in joint fishing waters’ And that’s because an animal or fish that is in joint waters is legally both a marine and estuarine resource and a wildlife resource.”

He said that joint rulemaking took place in the late 1970s or early 1980s, was revisited in the 1990s and readopted in 2022, at the direction of the governor’s office.

“At the time, it was really adopted based on what both boards were told to do, and that we would address this issue after it was readopted,” Waters said.

Included in the rules readopted by both with no substantive changes, which went into effect Sept. 1, 2022, coastal fishing laws and regulations administered by NCDEQ and the Marine Fisheries Commission apply to joint fishing waters except “the following inland fishing laws and regulations administered by the Wildlife Resources Commission apply to joint fishing waters and shall be enforced by wildlife officers: (1) all laws and regulations pertaining to inland game fishes; (2) all laws and regulations pertaining to inland fishing license requirements for hook and line fishing; and (3) all laws and regulations pertaining to hook and line fishing except as hereinafter provided.”

Commission Chairman Monty Crump of Richmond County told Coastal Review in a recent phone interview that during the Feb. 17, 2022, meeting with the governor’s office that he clarified that Wildlife Resources managed hook and line in joint waters. “I said I want to be clear, so there’s no misunderstanding” that while Marine Fisheries has made it clear that they do not agree with WRC having authority over hook and line in joint waters, the governor’s office was telling both agencies to adopt rules as written.

Crump, who owns a small family farm and has been on the commission since 2017, said he was asked during that meeting why he thinks the Wildlife Commission has hook and line authority, and “I said because it’s plainly clear in the general statute that Wildlife has hook and line authority in joint waters, which means all species, they consider coastal under them, and when they get into joint waters in inland waters, they’re under our jurisdiction. And they don’t agree with that, that is the crux of the whole deal, that statutory language.”

Waters told Coastal Review in an email that by rule, WRC has regulatory authority for species in joint fishing waters when taken by hook and line, and certain species listed as “game fish,” and Marine Fisheries Commission has regulatory authority over all other fishing activities.

“These differences in authority means that WRC and MFC can only implement seasons, size and creel limits within their respective jurisdiction. Therefore, there is a critical need for open communication between WRC and MFC/DMF when there is a regulatory change for a given species,” he said.

He said the Wildlife Resources Commission needs to know of a potential change six months in advance of when it is to be effective to have rules in place.

“In the case of recent changes for Flounder and Mullet, WRC did not learn of the change in time to implement a rule change. The result is that the DMF proclamation is effective in the MFC/DMF jurisdiction and WRC rule is effective in its jurisdiction,” he said. “Traditionally, seasons, size and creel limits have been communicated between agencies. And the WRC has promulgated rules that are consistent with MFC/DMF management. Recently DMF has implemented management changes through proclamation, not allowing WRC sufficient time to address the changes through rulemaking. This occurred with both Flounder and Mullet seasons.”

Waters continued that at this point, regulations for other species are substantially similar, if not identical.

“The WRC has tried to match our rules with MFC/DMF for those species for which they generally take the management lead. The flounder season is now closed in all waters, and we are trying to coordinate with DMF to address regulations for the 2024 harvest season,” he said, adding that the mullet season closure implemented by DMF through proclamation is different than the open season established by the WRC in rule.

Rule change exposes clash

Skinner explained that the conflicting seasons had been avoided in years past because of a Wildlife Resources Commission rule that was amended in 2022.

The rule, before being changed, read, “In inland fishing waters, Sea Trout (Spotted or Speckled), Flounder, and Red Drum (also known as Channel Bass, Red Fish or Puppy Drum) recreational seasons, size limits, and creel limits are the same as those established in the Rules of the Marine Fisheries Commission or proclamations issued by the Fisheries Director in adjacent joint or coastal fishing waters.”

The rule that went into effect March 15, now reads, “(a) The daily creel limit for flounder is four fish. (b) The minimum size limit is 15 inches. (c) The season for taking and possessing flounder is September 1 through September 14.”

Skinner noted that the recreational southern flounder season and/or bag limit has changed every year since Amendment 2 to the flounder management plan was adopted in the fall of 2019. “That being said, there’s no way the WRC could have thought that their new rule would have matched the DMF/MFC seasons or bag limits on any given year.”

There was no recreational season in the fall of 2019 because harvest had been allowed all year prior to adopting Amendment 2. In 2020, the season was Aug. 16 to Sept. 30, and a four-fish limit. In 2021, the season was Sept. 1-14, again with a four-fish limit. In 2022, the season was Sept. 1-30 with a one-fish limit.

Skinner said with the previous rule, the Wildlife Resources Commission acknowledged the Marine Fisheries Commission’s authority over joint waters, “which they now claim they have authority over, at least for the hook-and-line fishery. If they’ve always had authority over the hook-and-line fishery in joint waters, why wait decades to exercise that authority?” he said.

Next in the series: How did this unfold?