Frank Stick was in search of two things when he arrived on the Outer Banks in the 1920s: adventure and money. He found enough adventure to fill a lifetime but like many Bankers on the isolated barrier islands, he scrambled to pay the bills. Once one of the largest landowners, with property from Kitty Hawk to Hatteras, the artist turned developer lost many of his holdings during the Great Depression. Stick eventually recovered and developed the much-admired Southern Shores community with his son David and other partners. A complex man of shifting interests and unwavering opinions, Stick was both a conservationist who played an instrumental role in the formation of Cape Hatteras National Seashore and an avid land speculator who wrote of turning the Banks into a playground for tourists.

This is his story.

Supporter Spotlight

Chapter Two: The Nature Lover Turns Speculator

Read Chapter One: The Outdoorsman

In the summer of 1926, Frank Stick put aside his paint brushes and made the long journey from Asbury Park to the Outer Banks. Details about the August trip are scarce. It appears that Frank and a friend drove from New Jersey. But where they stayed or for how long is unclear. Years later, family members would say Frank came to go fishing, fell in love with the spare beauty of the Banks, and decided he wanted to live there. It is a good story and in keeping with the narrative that Frank and others crafted of the artist as a tireless adventurer who often made decisions from the gut. And for nearly a century it has gone unquestioned, repeated in numerous books and articles.

But the story is incomplete. Frank Stick was looking to land more than a few bluefish when he visited the Banks. His career as an illustrator whose paintings appeared on the covers of such diverse national magazines as Field & Stream, Redbook and Ladies Home Journal was beginning to unravel. Frank was restless and looking for a new, lucrative career. He had identified the Outer Banks as one of the most promising shorelines on the East Coast. His partner on the trip, Allen R. Hueth, was a wealthy main street real estate agent who owned or managed hundreds of properties around Asbury Park. True, they were fishing buddies. However, they brought along more than rods and reels on this trip. They also brought a plan, and cash, plenty of cash.

Hueth and Stick saw the Outer Banks as an opportunity, maybe even a way to get rich. Other than seven or eight small villages scattered here and there from Kitty Hawk to Cape Hatteras, there were miles and miles of empty oceanfront, rolling sand dunes, and maritime forests fronting the Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds. Unlike Asbury Park and other booming resorts along the northern New Jersey coast, where oceanfront lots sold for thousands of dollars, land on the Banks was cheap, costing only a few dollars. Many sales were on installment. All investors had to do was put down something and take an option on the rest, paying off as they went. With restless Americans looking to escape the summer heat, and an exuberant stock market refreshing pocketbooks, the moment felt ideal for a land boom at the beach.

Stick and Hueth arranged a meeting with Capt. Daniel Webster Hayman, a native of Kitty Hawk who piloted steamboats and yachts from Norfolk to Key West, and somehow had managed to come into possession of 30,000 acres on the Banks. Wanderlust caught Capt. Dan early in life and at the age of nine he had shipped on a three-mast schooner as a mess boy. In more recent years, he had piloted a millionaire’s yacht up and down the Florida coast, where a land boom was transforming mangrove forests and sawgrass into rivers of gold. Recognizing the possibilities, Capt. Dan had returned to North Carolina and begun investing in real estate.

Supporter Spotlight

All told, it is said Capt. Dan sold his 30,000 acres for about $200,000 – or about $7 an acre. That doesn’t sound like much today but it is worth recalling that some Bankers were giving away oceanfront lots for pennies at the time. Stick and Hueth bought a 2,300-acre tract near Kill Devil Hills that included the site where Orville and Wilbur Wright made the first heavier than air flights. They then added 6,000 acres near Nags Head, 8,000 acres between Oregon Inlet and Hatteras and a smaller tract running from the Atlantic Ocean to the Kitty Hawk Bay near the border of Kill Devil Hills and Kitty Hawk.

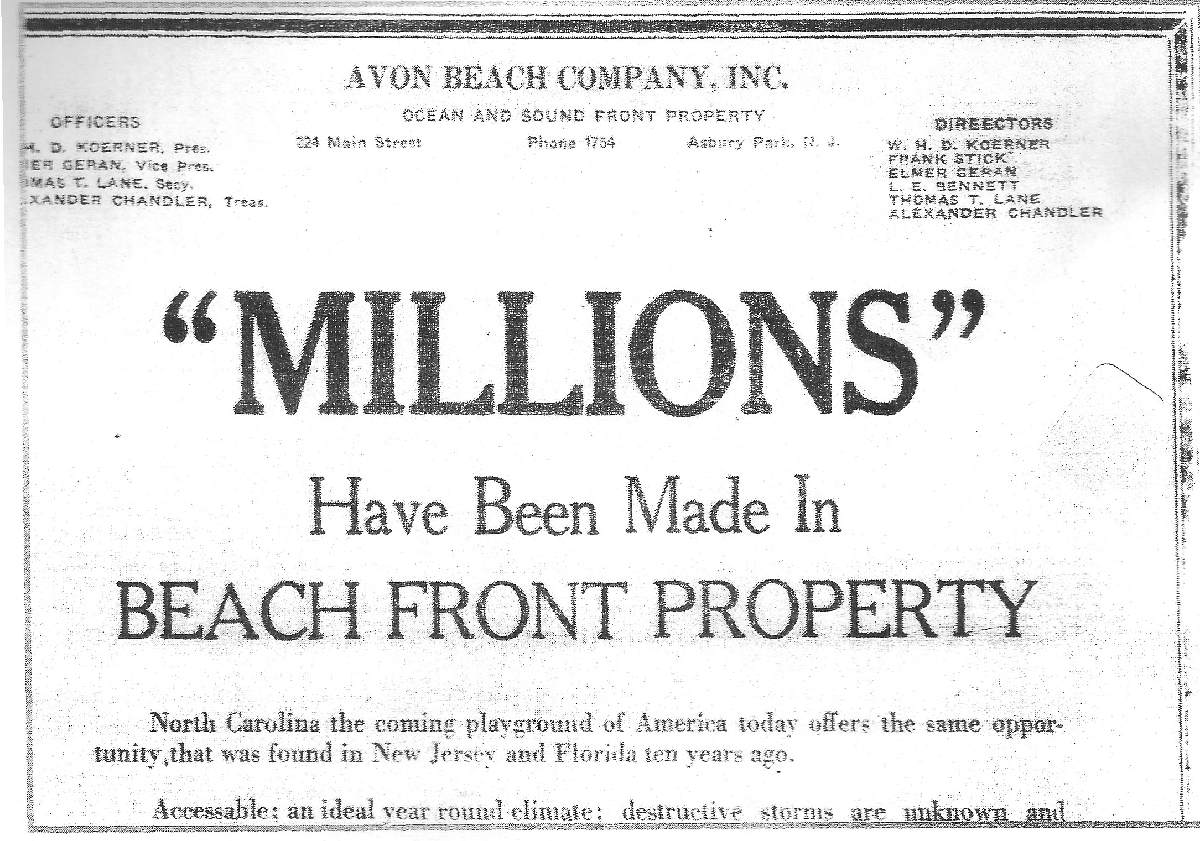

Almost immediately, Stick and his New Jersey partners began advertising in local newspapers. For example:

“MILLIONS”

HAVE BEEN MADE IN

BEACH FRONT PROPERTY

… shouted an advertisement in the Thursday, Oct. 21, 1926, edition of The Asbury Park Press.

North Carolina the coming playground of America today offers the same opportunity that was found in New Jersey and Florida ten years ago. Accessable (sic); an ideal year-round climate; destructive storms are unknown and North Carolina is conceded to be the most progressive and prosperous State in the Union. Lots as low as $100.00.

Upon returning home, Frank Stick began to recruit friends and business associates from Asbury Park to invest in his Outer Banks’ ventures. Frank’s Interlaken neighbor and fellow illustrator, Bill Koerner, purchased land near Kill Devil Hills. Elmer H. Geran, an attorney, banker, and former one-term congressman, joined Stick and Hueth in their recently formed North Carolina Coast Development Co. T.H. Beringer, an Asbury Park councilman, invested in 500 acres of Colington Island, a prized tract in the Albemarle Sound. Charles Baker and Susan Sutton, owners of the largest department store in Asbury Park, acquired the sand dunes that would eventually become the site of the Wright Brothers Memorial. Meanwhile, Stick formed a separate company, Hatteras Holding Corp., to buy coastal land and build lodges and hunting clubs for wealthy industrialists from the North. He brokered deals for the Phipps brothers, John and Henry, scions of a Pittsburgh steel fortune, and helped design and build hunting lodges for the brothers near Cape Hatteras and Buxton. In turn, the Phipps family provided Stick with a $12,000 loan to help him cover some of his debts, correspondence shows.

Stick and his fellow investors now owned thousands of acres of the Outer Banks. How many exactly? That’s hard to know. Hueth told The Asbury Park Press that they controlled 40 miles of oceanfront and bay in Dare County, which included the barrier islands from Kitty Hawk to Hatteras. Another story put the figure at 75 miles. Neither figure is credible. Frank’s son, David, the late, local historian, used a more believable 14 miles.

In any case, it was a lot. W.O. Saunders, editor and publisher of The Elizabeth City Independent, took notice. “A revolution has come to Dare County,” he wrote. “It is a bloodless revolution … but a revolution nevertheless. Wealthy Northerners … are slowly but surely acquiring mile after mile of beach and marsh lands.”

David Stick put it more simply. He called it “The Jersey Shore Invasion.”

~

In 1927, Frank and his partners announced plans for a resort north of Kill Devil Hills, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to Kitty Hawk Bay. It would be called Virginia Dare Shores, named for the first English child born in the Americas, near Manteo. As with most of Frank’s visions, it was eye-catching and creative. The design included a wide center boulevard named for Capt. Dan Hayman, with blocks of cottages running north and south. There was to be a pavilion for community events, a dock for the ferry shuttling vacationers from the mainland to the resort. A cement block cottage offered a place for Frank and his family to stay until he moved them permanently to the Banks. Frank also announced plans for two hotels – one a 200-room oceanfront structure near the site of the Wright Brothers’ flight and the other a 30-room hotel on Kitty Hawk Bay. The latter would be built immediately, he promised The Independent.

It was a heady time for Frank and his partners and the locals eagerly cheered their every move. The days of isolation and poverty were finally giving way to a new age. “It is impossible to stem the beginnings of a rush of visitors who are anxious to see the new region for themselves,” W.O. Saunders wrote.

Excitement and enthusiasm are one thing, actual development another. Frank and his partners struggled to find buyers. That wasn’t surprising considering the absence of roads or bridges connecting their planned resort to the mainland. For help selling his dream, Stick turned to Frank Winch, a former publicist for the circus who had recently directed a farewell tour for the showman Buffalo Bill Cody. Ordinary adjectives don’t quite do Winch justice. He was big, loud, excessively confident, and prone to exaggeration. Like Stick, he was a sharpshooter, big game hunter and a naturalist, which likely explains how Frank knew him. Prior to promoting Virginia Dare Shores, Winch had set up shop in Miami, selling the land boom there. “WANT TO MAKE MONEY?” one of his advertisements blared. “I HAVE MADE MONEY.” As the press agent for Coney Island, Winch once got into a row with local media for using the term “hot dog.” That was too “low brow for a summer resort,” he insisted. The proper term was “frankfurter.”

Frank met Winch at a Norfolk hotel and the pair agreed on a plan. Winch would operate out of Washington, D.C., and set up satellite offices in the big cities from Norfolk to New York. That May, the new partners held a get-to-know-us meeting with members of the Elizabeth City Chamber of Commerce and handed out courtesy cards for free ferry rides to their new pavilion on Kitty Hawk Bay. Winch grandly told the crowd that sales had already reached $100,000, and that construction of 15 to 20 cottages would begin in two weeks.

Prior to the gathering, Winch visited W.O. Saunders at his home to celebrate Saunders’s birthday. According to a story in The Independent. Winch presented the publisher with “a handsome silver service … and a beautiful 24 carat virgin gold ruby ring.” The newspaper described the offerings as birthday presents.

Following the meeting, Saunders’s newspaper published a glowing report on the Virginia Dare Shores project, referring to Stick and his partners as “splendid fellows” who were transforming the Outer Banks. He also informed readers that his newspaper had printed “a beautiful supplement” for the developers. Written by Winch, the glossy, 16-page report was filled with bluster and exaggerations. It repeated earlier claims that the partners controlled most of the Outer Banks; that there were “smooth hard roads,” and that Virginia Dare Shores was “ready for immediate occupancy.”

It was fantasy and Frank Stick knew it. There were no paved roads. No cottages ready for immediate occupancy. While they were moving forward, progress was slow and money was tight. Little could Frank know, but his vision of turning the Banks into a summer playground was about to implode.

Next in the series: Setbacks to a Dream