Update Oct. 3: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service officials announced Monday that they are extending the public comment period from Oct. 15 to Oct. 30 for the draft environmental assessment for cyanobacteria treatment in Lake Mattamuskeet. Comments may be emailed to mattamuskeet@fws.gov.

Original story:

Supporter Spotlight

SWAN QUARTER — Officials at Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge are considering permitting a relatively new pesticide in a trial project to study its effect on blue-green algae that has plagued the state’s largest freshwater lake.

A draft environmental assessment of the proposed treatment on Lake Mattamuskeet was released earlier this month. Public comments are due by Oct. 15 and may be emailed to mattamuskeet@fws.gov or mailed to Mattamuskeet NWR, 85 Mattamuskeet Rd, Swan Quarter, NC 27885.

Based on the product’s warning label, there are concerns that it could be a risk to the migrating waterfowl and other birds that visit and breed at the refuge, which in large part was created to be a sanctuary for those birds. Added to that worry, the algae, also known as cyanobacteria, is a symptom of numerous unhealthy factors plaguing the lake’s ecosystem, including excess nutrients and loss of submerged aquatic vegetation, which officials call SAV, that requires more complex remedies than merely ridding it of an algal bloom.

“This is not seen by us as the solution for restoration of the lake, or restoration of SAV in and of itself,” Mattamuskeet Refuge Manager Kendall Smith told Coastal Review. “It’s a trial treatment. We’re learning a lot, but it’s an opportunity to evaluate a technique that may be helpful to the overall strategy of restoring SAV in the lake.”

Smith also said that while the algaecide may be dangerous to birds in its pellet form, it is safe once dissolved. And there would be no shoreline or land areas, he said, where the birds would be exposed to the pellets.

Supporter Spotlight

Still, the undissolved pellets can remain on the water’s surface before that happens, said Ramona McGee, staff attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center in Chapel Hill.

“It’s hard to see that this can be considered compatible use if this is toxic to birds,” she told Coastal Review.

Before the refuge would be able to implement the trial cyanobacteria treatment, it would have to secure permits from the North Carolina Department of Water Resources and agency approval from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s pesticide use proposal system. The earliest the work would begin is this winter, Smith said.

According to the Fish and Wildlife Service proposal, a sodium percarbonate-based algaecide, Lake Guard Oxy, would be used over approximately 600 acres, isolated in several areas around the lake’s perimeter. The agency agreed to pursue the pilot study after the refuge was approached in 2022 by the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences and Pittsburgh-based contractor BlueGreen Water Technologies, which was seeking to evaluate the cyanobacteria treatment in a North Carolina water body. Project funding includes $5 million appropriated by the North Carolina General Assembly in 2021.

“This treatment is intended to reduce the cyanobacteria populations to allow for the re- establishment of beneficial algae and phytoplankton communities and to increase water clarity in Lake Mattamuskeet,” an agency document said.

Online information about Lake Guard Oxy on the Environmental Protection Agency website dated March states under the “environmental hazards” heading: “This pesticide is toxic to birds. Do not apply this product or allow it to drift to blooming crops or weeds while pollinating insects are actively visiting the area.”

Information on BlueGreen’s website, however, states that the product’s formulations are Environmental Protection Agency- and National Science Foundation-certified, “and are made from ingredients that have been safety-approved causing no harm to human, animal, or plant life.”

McGee, with the law center, also said that under the National Environmental Policy Act, federal agencies are required to do an informed analysis before issuing an environmental assessment.

By definition, a pilot project is inherently experimental, she said. But the refuge had already issued a special use permit in January to BlueGreen, which has installed solar-powered probes to monitor parts of the lake, in addition to independent monitoring by UNC.

Monitoring environmental impacts would also continue during and after treatment.

“Those are the sort of questions the Fish and Wildlife Service should’ve considered,” she said. “This is being done backwards, in terms of analyzing the effects.”

McGee said the law center had been coordinating with environmental groups and planned to submit comments.

The North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review, also plans to submit comments about its concerns, said Alyson Flynn, the nonprofit’s coastal advocate in its Wanchese office.

“The use of experimental chemicals is not going to solve the water quality and flooding problems at Lake Mattamuskeet,” Flynn said.

Once the bustling centerpiece of Hyde County’s rural mainland communities, Lake Mattamuskeet experienced rapid degradation in its water quality and overall environmental health over recent decades. Despite that, the 40,000-acre lake, 6 miles wide, 18 miles long and an average of 2 feet deep, maintains its otherworldly beauty, surrounded by swamp forests, marshes and upland forests.

The refuge, which totals about 50,000 acres, includes a boardwalk near the lake that winds through wetlands filled with old cypress knees and craggy old trees where visitors might half-expect to see gnomes. Most famously, the refuge attracts thousands of wintering tundra swan and other migratory waterbirds, as well as numerous species of resident duck. It is also home to numerous mammals, including black bear, bobcat and endangered red wolves.

“Unfortunately, due to excessive nutrients, reduced flow to Pamlico Sound, and an overabundance of invasive common carp, the lake conditions began to decline in the early 1990s in both water quality and clarity,” according to the document. “During this period of decline, water quality monitoring documented increases in nutrients, harmful algae blooms, and turbidity in the lake.”

Carp have contributed to the lake’s problems by not only eating the submerged grasses, but also by creating more suspended sediments that block sunlight from reaching the vegetation.

Smith said that the refuge is working on finalizing a contract to have most of the carp removed in the near future.

With the depletion of the underwater vegetation, waterfowl lost a vital source of nutrients. Although the birds still come to the refuge in large numbers, they go to the duck impoundments on and around the refuge for food and use the lake for a rest stop.

Drainage into the lake from surrounding farmland and bird impoundments has been associated with the increased level of nutrients, which contributed to eutrophication that led to dominance of phytoplankton.

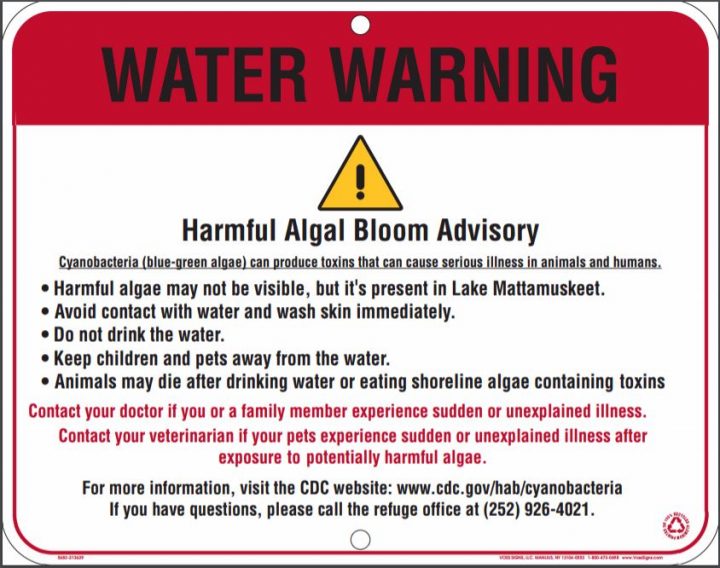

In 2016, the lake was listed by the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Resources as impaired waters, based on high alkalinity and levels of chlorophyll-a, both indicators for cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms that produce cyanotoxins. The refuge has posted warning signs at the lake since 2019 to inform the public about the danger of the blooms, which can cause skin rashes and itchy or sore eyes, ears or noses.

Described as photosynthetic, single-celled aquatic organisms by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cyanobacteria are prone to quickly multiply in warm, quiet waters that have high amounts of nutrients.

The slimy green coating recognized as algal blooms in water bodies is not present at Lake Mattamuskeet, Smith said. Rather, it appears as a cloudiness in the water.

Confronted with the wipeout of lake grasses and compromised ecosystem in 2017, refuge officials seeking a holistic approach to addressing issues on a watershed scale reached out to stakeholders to plan a collective effort to improve water quality. Led by the Coastal Federation, the Lake Mattamuskeet Watershed Restoration Plan, released in 2018, established best management practices and cooperative strategies to improve drainage and restore submerged grasses.

Smith said that the treatment could be one of the tools used to restore water quality, but it won’t solve all the lake’s problems.

“We do think that reestablishing SAV somewhere in the lake is a step in the right direction,” he said.