A new discovery in one type of color-changing fish could be used to help artificial intelligence developers fine-tune how smart systems respond in a changing environment.

Research headed by University of North Carolina Wilmington assistant professor Lorian Schweikert has found that hogfish, popular among recreational fishermen for its mild, sweet meat, have a cell hidden underneath their skin that allows the fish to observe itself change color.

Supporter Spotlight

This is the first time a photoreceptor, or a cell that responds to light, has been found to exist in skin rather than in the central nervous system of a vertebrate animal, one that has a backbone and skeleton.

The study, published last month, found light sensors concealed behind a cell that researchers did not know existed until now.

This finding answers a long-standing question about why, at least for hogfish, light sensors are in the skin, said Schweikert, a sensory biologist.

“It’s also cool because it’s whimsical to think these animals are watching their own color change,” she said.

They’re able to do that thanks to the color-changing cells, which work like a Polaroid camera that lets the fish take a picture of itself to monitor itself changing color.

Supporter Spotlight

Schweikert said to think of yourself getting dressed in the morning without a mirror and without the ability to bend your neck. You would not be able to see whether you put on your clothes correctly.

Hogfish, named for their long, pig-like snouts, which they use to graze for crustaceans underneath the sand, are tasty to humans, sharks and barracuda alike, making their ability to camouflage paramount to their survival. These fish are typically found throughout the Caribbean and from North Carolina to Bermuda as well as the northern coast of South America.

“In the case of color-changing animals that frequently do this for camouflage to hide from predators it’s a life or death decision and they need a way of monitoring the quality of their performance,” Schweikert explained. “In physiology we call this a feedback system, sensory feedback. It’s a way of monitoring our own performance.”

This incredible feedback system could aid the ever-evolving world of artificial intelligence.

From robotic vacuum cleaners and self-driving cars to voice-activated systems like Amazon Echo or Apple’s Siri, smart systems use sensory feedback to understand their own performance.

“Basically, by looking at how systems like in the skin of these fish, how they’re organized, how they work, we can take those kinds of principles and develop our new solutions to that kind of technological problem,” Schweikert said.

This is all a result of a fishing trip she went on in the Florida Keys roughly seven years ago while a graduate student at the Florida Institute of Technology.

She caught a hogfish, and, after it died, she picked it up to find the side of the fish that had been facing the boat’s deck had taken on a white color and a bit of a pattern that matched the deck itself.

“There’s many color-changing animals in nature that do unbelievable displays of color change, but what surprised me was the fact that this color change happened post mortem in this animal and it made me think that the skin could do this maybe independently of the eyes and of the whole system,” Schweikert said.

By that time scientists knew that virtually all animals that change their skin color to camouflage have light-detecting systems, or “visual systems.”

But no one understood why.

To be crystal clear, Schweikert said, she now knows that the color-change she witnessed on the boat several years ago was a response simply to the pressure or temperature of the boat deck.

“That experience gave me the idea to investigate skin further,” she said.

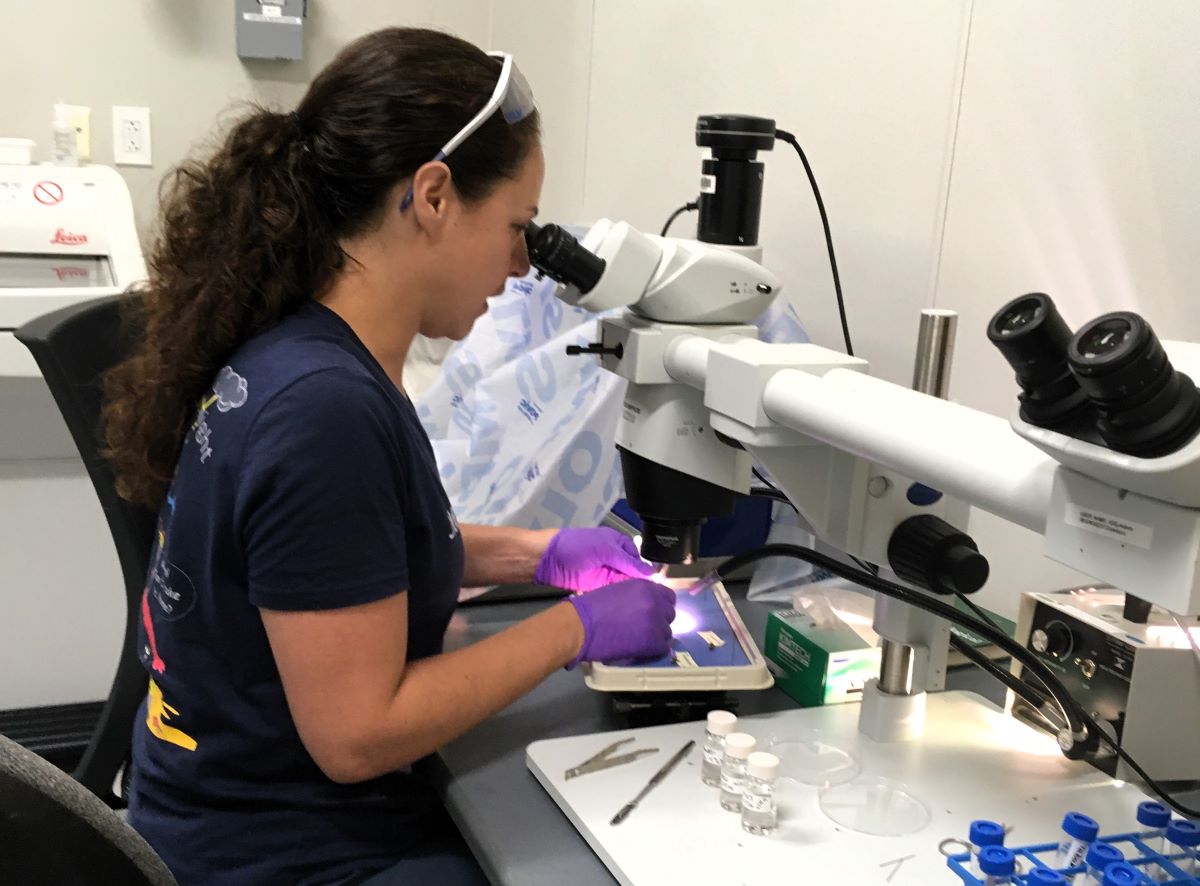

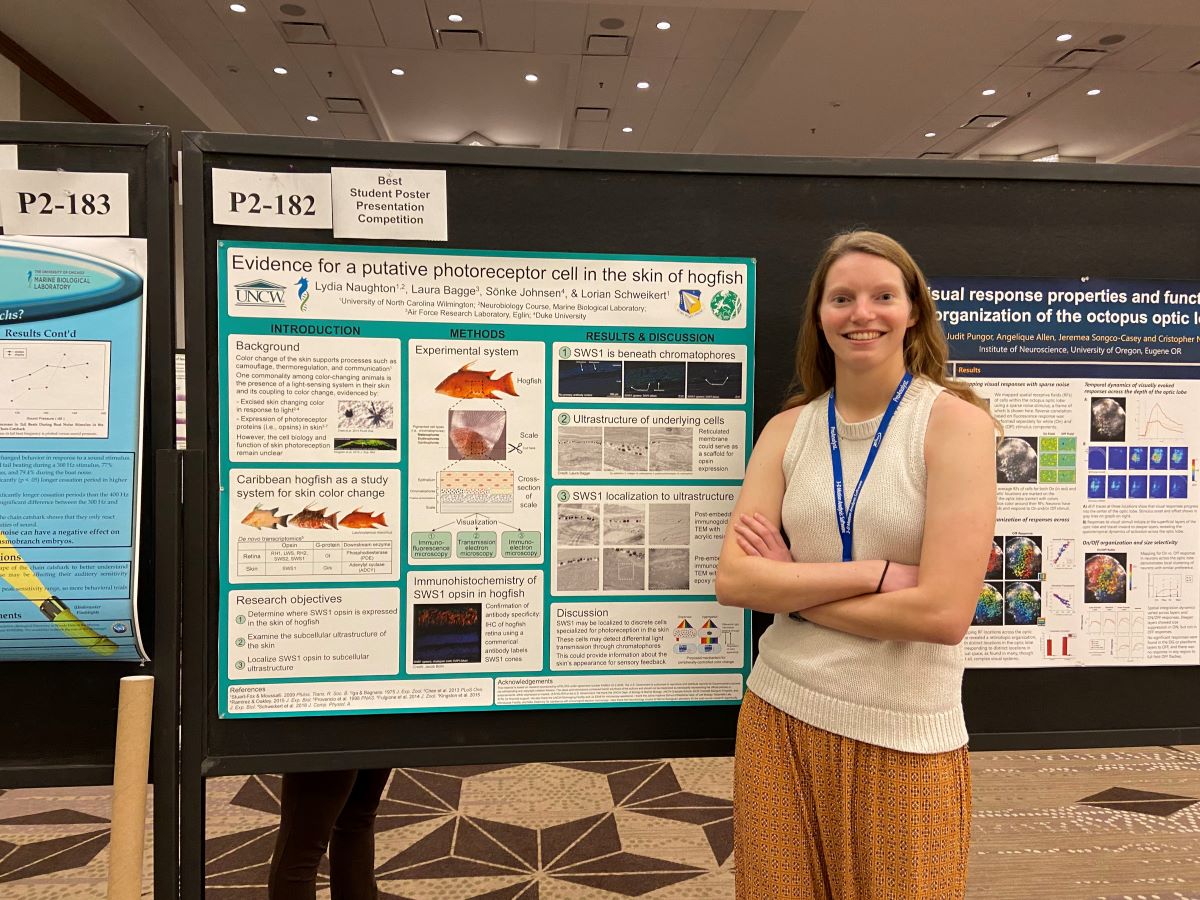

Through her postdoctoral years at Duke University and Florida International University she collected data, which she then shared once she was hired at UNCW with students she recruited to launch a research program to collect the data would answer her question of “why.”

Doctoral candidate Lydia Naughton, who, along with undergraduate Jacob Bolin co-authored the hogfish study with Schweikert, is further investigating the characteristics of the novel cells in those fish. Maureen Howard, an honors student, is studying light sensing systems in the skin of flounder.