In a steamy hot summer of freak storms and horrific wildfires, recent cases of infections from vicious, flesh-eating bacteria that can kill within 48 hours of exposure in warm, brackish water has only added to a sense of foreboding.

It’s not that our sounds and marshes are dirty or disease-ridden, says a veteran microbiologist; it’s that warm estuarine waters can be dangerous to people with vulnerable immune systems who have fresh wounds or who have eaten raw oysters.

Supporter Spotlight

“The last thing I want to do is scare people away from the beach, when it’s a very rare, rare situation,” James D. Oliver, professor emeritus at University of North Carolina Charlotte, Department of Biological Sciences, said in a recent interview. “But if you’re a susceptible person, you’re at risk.”

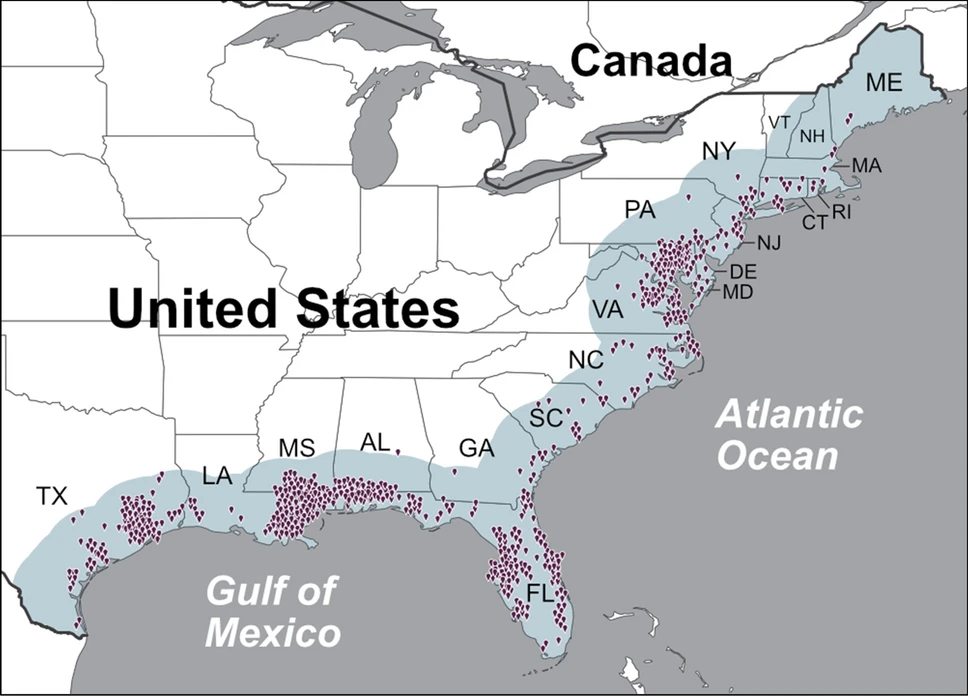

Although Vibrio vulnificus, a genus that’s one of the fastest growing bacteria known, has long been present in the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic coastal estuarine waters, infections from the pathogen have been becoming more prevalent in northern waters as the climate becomes increasingly warmer.

Of the 100 or so Vibrio bacteria, including one that causes cholera, vulnificus can be the most lethal.

State health officials reported that three people from North Carolina — including one case in Nags Head — died in July from Vibrio infections.

Three people in the New York City metropolitan area also have died since July 1 of Vibrio infections, and another person was hospitalized and released, the New York governor’s office reported.

Supporter Spotlight

But Vibrio vulnificus, unlike the familiar water-borne contaminants from animal feces or septic spills, are naturally occurring in marine waters.

“They’re there all the time,” Oliver explained. “But when the water is cold, they go into a dormant stage and you won’t get infections in the winter. So all the infections are from like May until October.”

Typically, people who get infected are those who have liver diseases, including hepatitis, are older than age 60, or have suppressed immune system diseases such as diabetes, Oliver said. And for reasons scientists don’t completely understand, 85% to 90% of infection cases are in men over age 40.

Oliver, who began researching Vibrio vulnificus about 45 years ago, said the reason for the gender differences may be related to protective factors of estrogen in females, or because nearly all cases of liver cirrhosis are in males, he said. Unfortunately, he added, a large percentage of those with cirrhosis, which is not a young man’s disease, are unaware of it until it has progressed.

“And that is the No. 1 risk factor for coming down with it after eating raw oysters, or after getting a cut, for that matter,” Oliver said.

The bacteria activates when the water temperature reaches about 68 to 70 degrees, and does fine at hotter temperatures. Once they start dividing, their numbers can increase rapidly. It’s a matter of having the right combination of salinity and temperature, Oliver said. The higher the saltiness, the less the bacteria thrives.

“They like relatively low salinity water,” Oliver said. “You won’t find this out in the open ocean.”

Salinity levels in estuarine waters typically range between 2 to 25 parts per 1,000, he said. The ocean is about 35 parts per 1,000. In severe droughts, brackish waterways sometimes become too salty for the bacteria’s liking, he said, but that has been unusual.

Warming coastal waters from climate change impacts have resulted in a northerly spread along the U.S. East Coast of Vibrio wound infections, according to a March 2023 article in Scientific Reports, “Climate warming and increasing Vibrio vulnificus infections in North America,” authored by Oliver and eight other scientists.

Between 1998 and 2018, the report said, the number of cases increased eightfold, from 10 to 80 a year, and shifted northward about 30 miles.

By 2041 to 2060, the range for infections would be expected to encompass the New York City region and double in numbers, the report said. By the end of the century, unless carbon emissions are reduced, it could be found in every state.

Currently, Vibrio wound infections are about 20% fatal, Oliver said. Those with cuts who don’t have underlying health conditions could still get an infection, but it wouldn’t be life-threatening. People also can get infected by ingesting raw oysters, and that is extremely dangerous to people with the risk factors. Of those cases, 100% result in hospitalization and 50% are fatal.

“So it is the by far the most fatal foodborne disease in the world,” Oliver said.

In fact, 95% of all seafood-related deaths in the U.S. are due to eating raw or undercooked oysters, the report said. Ingestion also accounts for 93% of Vibrio infections from raw or undercooked seafood consumption. The pathogen is not a risk to pets or other animals, Oliver said.

“While the concentration of V. vulnificus in estuarine waters is typically quite low,” the report said, “it becomes concentrated in such molluscan shellfish as oysters and clams due to their efficient use of filter-feeding to obtain food.”

Most ingestion cases — about 100 to 200 cases a year in the U.S — are from Gulf oysters because of their habitat’s warmer waters and lower salinity, Oliver said, adding that he is not aware of any cases from North Carolina oysters.

“Ours are very safe, actually,” he said.

Since 2019, eight of 47 reported Vibrio cases among North Carolina residents have been fatal, according to a July 28 press release from the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Of the three most recent fatalities in July 2023, the release said, all were exposed to brackish waters. Two of the victims had scratches and the third had consumed personally caught seafood that was not shared or distributed.

In an email responding to an inquiry from Coastal Review about two recent local cases, the Dare County health department said that one case, which was a fatality, was reported on July 20 in Buzzard Bay in Albemarle Sound south of Colington Island on the Outer Banks, and another confirmed case was reported on July 25 to have been acquired in the ocean in Nags Head. That person was a visitor, and there are no updates on a condition.

A third case was confirmed from a person who ate raw oysters on July 19 from a facility in Dare, the email said. The oysters were from Virginia, according to the New Jersey Department of Health. As of the last update on July 25, the person was reported to be recovering at home.

There have been a total of nine confirmed and two probable cases of Vibrio in Dare County since 2018, the health department said.

An infection is diagnosed when tests find the bacteria in the stool, wound or blood of a patient, the email said.

Privacy regulations limit health officials from providing certain details and names, but numerous reports on social media and news outlets identified a recent fatality as a 71-year-old man from Nags Head, who died on July 21 after being cut by a crab pot in Buzzard’s Bay.

Hospitalizations related to Vibrio can require intensive treatment, especially for ingestion cases, and can be very costly, Oliver said.

As its apt “flesh-eating” epithet describes, the bacteria can inflict gruesome damage on the human body with stunning speed. Victims can suffer sepsis and horrific oozing wounds, sometimes requiring amputations to save their lives.

Major symptoms of wound infections include fever, with edema and cellulitis at the site. The incubation period is rapid, averaging only 16 hours.

The bacterium, which can start dividing in less than 15 minutes, is very sensitive to antibiotics, Oliver said, but effective treatment is a matter of timing. Dabbing a cut with peroxide is unlikely to prevent it from getting into the bloodstream, so those with health risks should be vigilant about seeing a doctor.

“By the time it gets in, it’s almost too late,” Oliver said. “And people dying within hours of admission to a hospital is not uncommon.”

In a paper Oliver wrote with a colleague, it detailed the progression of a Gulf Coast fisherman admitted to the hospital with a small wound that looked like a swollen spider bite, and within four hours it became a large lesion, and then it spread to multiple fluid-filled lesions on his body. Despite treatment with several antibiotics, he died 28 hours after he was admitted.

In cases of infections from raw oyster ingestion, symptoms are fever, chills, nausea, abdominal pain, hypotension and development of secondary lesions, according to a paper Oliver wrote. The incubation period averages only 26 hours after ingestion. Again, time is of the essence for antibiotic treatment. Those who wait three days have a 100% fatality rate.

The “flesh-eating” quality of the bacteria is caused by very powerful enzymes that begin to degrade human tissue, Oliver said. In ingestion, it goes through the stomach down to the intestines, and then goes through the intestinal wall into the blood. It then begins to spread throughout the body and come out at the skin in multiple lesions.

But wound infections are typically more contained to the site of the cut or bite, which explains why they’re less lethal.

Oliver recommended that people with any health risks who were in brackish water and have any cuts, scratches, recent tattoos or unhealed bug bites need to be proactive and act as soon as a cut shows any sign of infection. Or if they recently ate raw oysters and start feeling unwell, they need to see a doctor as soon as possible. What is important is telling the health care provider of the exposure or ingestion, and any immune system issues.

As the climate warming report emphasizes, the challenge to pubic health is likely to increase with warming seas, and more public awareness programs are called for.

“The northward V. vulnificus infection expansion stresses the need for increased individual and public health V. vulnificus awareness in these areas,” it said. “This is crucial as prompt action when symptoms occur is necessary to prevent major health outcomes.”