Second in a series.

A little-noticed rule in the North Carolina Farm Act of 2023 could bring noticeable changes to North Carolina’s streams, lakes, reservoirs, ponds and estuaries, and some conservation advocates are worried.

Supporter Spotlight

This new provision limits civil penalties for removing timber in a riparian buffer “in violation of rules applicable to that riparian buffer” from a maximum of $25,000 per violation to the civil penalty being capped at no more than the value of the timber removed.

A quarterly report released last week by the North Carolina Cooperative Extension forestry office shows that the most recent state-wide average standing timber prices range from $7.57 to $41.44 a ton, depending on the species, quality and product.

North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality Deputy Secretary for Public Affairs Sharon Martin explained last week that the agency is incorporating the legislative changes into the enforcement process and each civil penalty is determined based on the specific details of the case and the applicable rules and regulations.

“The changes may limit the maximum amount of the penalties that can be issued,” she said.

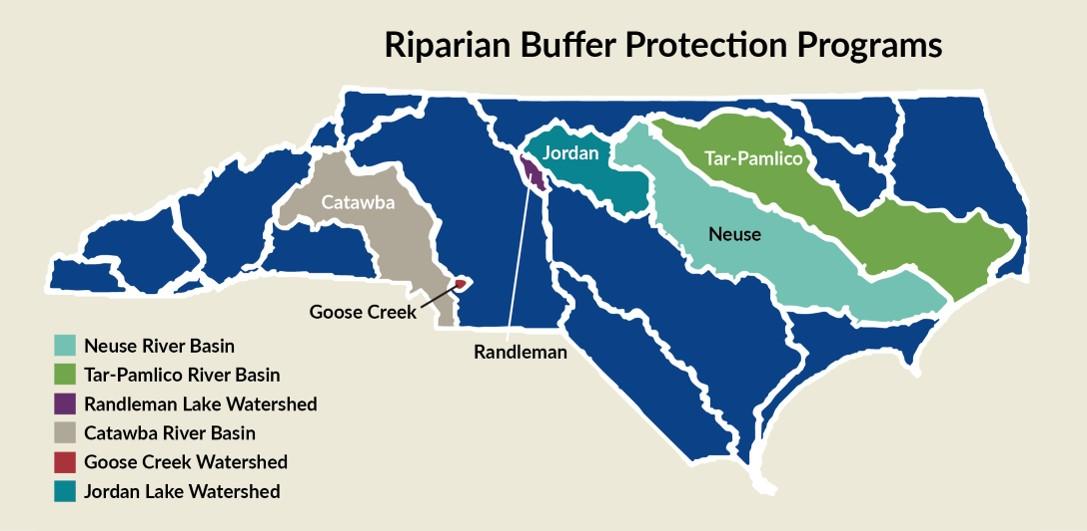

A riparian buffer is a vegetated area with native trees, shrubs and plants adjacent to an estuary, stream, lake or pond that stabilizes the shoreline, provides habitat and filters pollutants. The Division of Water Resources established riparian buffer rules to protect water quality in the Neuse River, Tar-Pamlico River and Catawba River basins and Randleman Lake, Jordan Lake and Goose Creek watersheds.

Supporter Spotlight

NCDEQ’s Division of Water Resources finds out about potential violations through complaints from residents or referrals from the North Carolina Forest Service, Martin explained.

“After an investigation, DWR determines the appropriate course of action and amount of civil penalty, if appropriate. If a civil penalty is assessed, severity of impact is one of the main considerations when determining amount,” she said.

This is the same Farm Act, also known as Senate Bill 582, that sparked outcry over a provision that amended how the state defines and protects wetlands. The act passed in late June, despite the governor’s veto that he based on objections over the wetlands provision.

Southern Environmental Law Center Senior Adviser Derb Carter told Coastal Review Monday that while none of the other provisions in the Farm Act received as much attention as the repeal of the state wetlands protections, this gutting of riparian buffer regulation is also now law.

With this civil penalty change, you can sell the timber for what it’s valued, then use that money to pay your fine. If you’re allowing trees to be cut and presumably sold – and they can fine you no more than what you receive for cutting the trees — “It’s made the tree protection and buffers pretty much a joke,” Carter said.

Sound Rivers Executive Director Heather Deck said Thursday that she is concerned the lowered penalty will simply become the “cost of doing business.”

Sound Rivers is a nonprofit organization that works to protect the neighboring basins of the Neuse and Tar-Pamlico rivers that extend from the Piedmont to the coastal plain and have sizable drainage areas entirely within the state. Both empty into the Pamlico Sound.

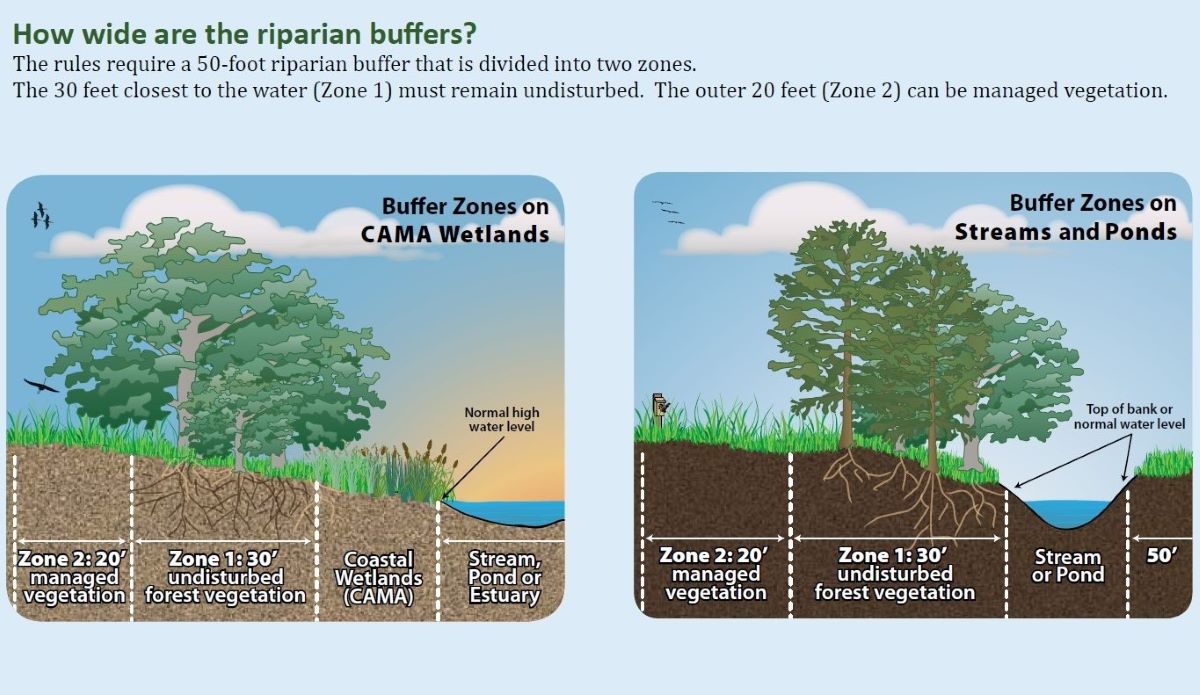

These two basins require a 50-foot riparian buffer, with the 30 feet closest to the water, or zone 1, required to remain undisturbed, and the outer 20 feet, or zone 2, can be managed vegetation. In the 20 coastal counties, the riparian buffer is measured from the landward edge of the Division of Coastal Management’s wetland boundary, according to NCDEQ.

Deck said that riparian buffers, or treelined waterways, are the most cost-effective tool at keeping our waterways clean and healthy for all uses.

“Keeping trees on the banks of rivers and streams and creeks is the simplest, most-efficient, cheapest option for protecting waterways and trying to keep them clean,” Deck continued. “Now you basically cut out that financial penalty for enforcement that would have incentivized some not to cut trees.”

The legislature has been for the last decade undermining environmental protections in favor of developers, and this is no different, Deck said.

“This move, in our opinion at Sound Rivers, takes away incentives not to cut trees while also putting a greater burden on the Department of Environmental Quality who is already overworked and under-resourced,” Deck said. This penalty change will result in more buffer violations and tree loss along river and stream banks, putting additional strain on the already understaffed agency.

Deck recognized that many remove trees to have an unobstructed view of the water, and “you can either have that, or have water that you want to swim and fish in. It’s as simple as that,” she said. “Keeping trees where they’re meant to be along the rivers, creeks and streams is very important. And this legislation will make it harder for us to do that.”

Coastal Carolina Riverwatch Executive Director Lisa Rider agreed that recent legislative actions have caused the state to move backward from “any progress we’ve made to protect the quality of water and life in coastal North Carolina.” The nonprofit advocates for the White Oak River Basin.

Rider added that, as a whole, some of the components to the recent Farm Act will have devastating outcomes with long-term effects on the local economy, just as much as the ecology.

“Here on the coast, downstream of the cumulative impacts, we are continuing to hear an outcry of concern from local commercial and recreational fishers about the lack of water and habitat protections by the state. We hope that in the future, these coastal voices are heard much louder by decision makers in Raleigh,” she said.

North Carolina Farm Bureau Federation Natural Resources Director Keith Larick told Coastal Review that while the buffer violation penalties language would restrict the amount of the civil penalties, he believes the state can still require the landowner to replant trees to replace those removed.

The provision went into effect July 1, just before the standing timber price numbers for the second quarter of 2023 were released last week by the Cooperative Extension’s forestry office. The quarterly report is through an agreement with Timber Mart-South, a nonprofit that provides trend data for timber.

This quarter, the statewide average prices for pine pulpwood is $7.57 a ton, pine chip-n-saw is $21.10 a ton, pine sawtimber is $30.02 a ton, hardwood pulpwood is $4.49 a ton, mixed hardwood sawtimber is $28.77 and oak sawtimber is $41.44 a ton.

Pulpwood is a tree or log used to manufacture paper, absorbent pulp, cardboard, fiberboard and other wood fiber-based products, and are typically the lowest-value product. Chip-n-saw is lumber produced from medium-sized pine trees, and sawtimber is a log or tree large enough and of suitable quality to be sawn into lumber, according to the North Carolina Forest Service.

N.C. State University College of Natural Resources professor and Department Extension Leader Dr. Robert Bardon said in an email response to questions that these standing timber prices are average prices for all of North Carolina. “This is the price paid to the landowner who owns the timber prior to it being harvested,” he said.

Bardon, referencing information from Forest2Market, explained that an acre that is clear-cut can produce, on average, about 87 tons of sawtimber-size trees and smaller. If an area is being thinned, or pulpwood-size trees are removed, then it would produce on average about 32 tons an acre.

If the state uses these recent numbers to determine the civil penalty, an acre of sawtimber would be valued between $2,612 and $3,605, depending on the tree species. An acre of pulpwood-sized pine trees would be valued at $242 and hardwood pulpwood at around $143.

Other provisions

The Farm Act adds to the farm digester system general permit that the “collected gases shall be used as a renewable energy resource as quickly as feasible, but within six months of the collection of the gases, and during that period the gas shall be flared rather than vented.”

Martin with DEQ said that this digester section adds specific guidance on the usage of the collected gases as a renewable energy resource and sets timelines for utilizing the collected gases, which is within six months of starting gas collection.

Larick said that the digester provision allows a farmer some flexibility — up to six months — to line up an outlet for the collected gas while still qualifying for the digester general permit instead of an individual permit. “The condition about flaring the gas for a maximum of six months was added to ensure that the methane was not just vented to the atmosphere in the meantime.”

Also in the Farm Act, the Environmental Management Commission has been directed to withdrawal the aquaculture national pollutant discharge elimination system, or NPDES, general permit that took effect Dec. 1, 2021, for discharges from seafood packing and rinsing, aquatic animal operations, and similarly designated wastewaters and revise the permit to be “substantively identical to the previous general permit.”

Martin clarified that this provision primarily applies to trout farms in western North Carolina.

Larick reiterated that the section of the Farm Act that requires changes to the NDPES permit was added at the request of trout farmers.

“The main issue that they had was the expense and time needed for the sampling in the most recent permit. The sampling frequency and number of parameters were increased, and they would be required to conduct composite samples instead of grab samples. The smaller trout farmers were especially concerned about the monitoring provisions,” he said.

Read part 1: Analysis: Farm Act strips wetland safeguards, mitigation