HARKERS ISLAND – The Hannah, a sailing ship blown off course on its voyage from Sierra Leone in Africa to Charleston, South Carolina, arrived at Ocracoke Inlet for provisions in 1759. Its cargo was human, 301 captives, but the records provide no details on what happened to the 258 or so surviving Africans who disembarked at Portsmouth Island.

Those and at least 343 other documented captive African people were honored and remembered Saturday during a ceremony at the end of the road on Harkers Island. The event was to dedicate identical markers to be placed at Portsmouth Village and about 39 miles south at the Cape Lookout National Seashore visitor center on Harkers Island acknowledging that this North Carolina port was part of the horrific Middle Passage.

Supporter Spotlight

Tyisha Teel of Beaufort was one of the speakers during the ceremony on the grass overlooking Back Sound at Shell Point, just across the road from the visitor center. She described how history is painful and embarrassing at times, but those feelings should motivate people to bring positive change.

“We should be motivated to take what we know and to do more with it to bridge the divides of inequality, of racism, of ageism — any of the ‘isms’ that are out there,” Teel said. “How do we make it a lasting change? We start first with acknowledgement, which is exactly what this ceremony is doing, acknowledging the history of where we come from, of the Africans who were enslaved and brought over through the Middle Passage, and the Black history of this country. But yet, I want us to remember that our Black history is American history. It happened here, it is the Americas, it is us, it is all of us.”

Cape Lookout National Seashore Superintendent Jeff West said that from its establishment in 1753, Portsmouth was an important maritime port to the central North Carolina region. He said that throughout Portsmouth’s history until about 1861, half of the population of Portsmouth were enslaved people.

“Enslaved African Americans were brought to Portsmouth to labor. They served as stevedores. They served as lighter tenders. They served as pilots. They served as sailors,” West said. “Another large contingent of enslaved people were brought in through Portsmouth to be sold and traded inland into a life of bitter slavery.”

West said he finds the topic difficult to discuss.

Supporter Spotlight

“I’m a historian by training. So, as a historian, I have absolutely no problem reviewing facts, placing them in context, explaining why things happen from a strictly factual perspective. As a human being I, to this day, I cannot understand or see how people could treat other people that way. I can’t understand it. That’s the human side of me.”

West said that part of the National Park Service’s mission is to tell the story of people and places and to tell it honestly and without prejudice.

“I’ve had to do that in many different places. Sometimes it’s hard, but it is the truth. Truth is important,” he said.

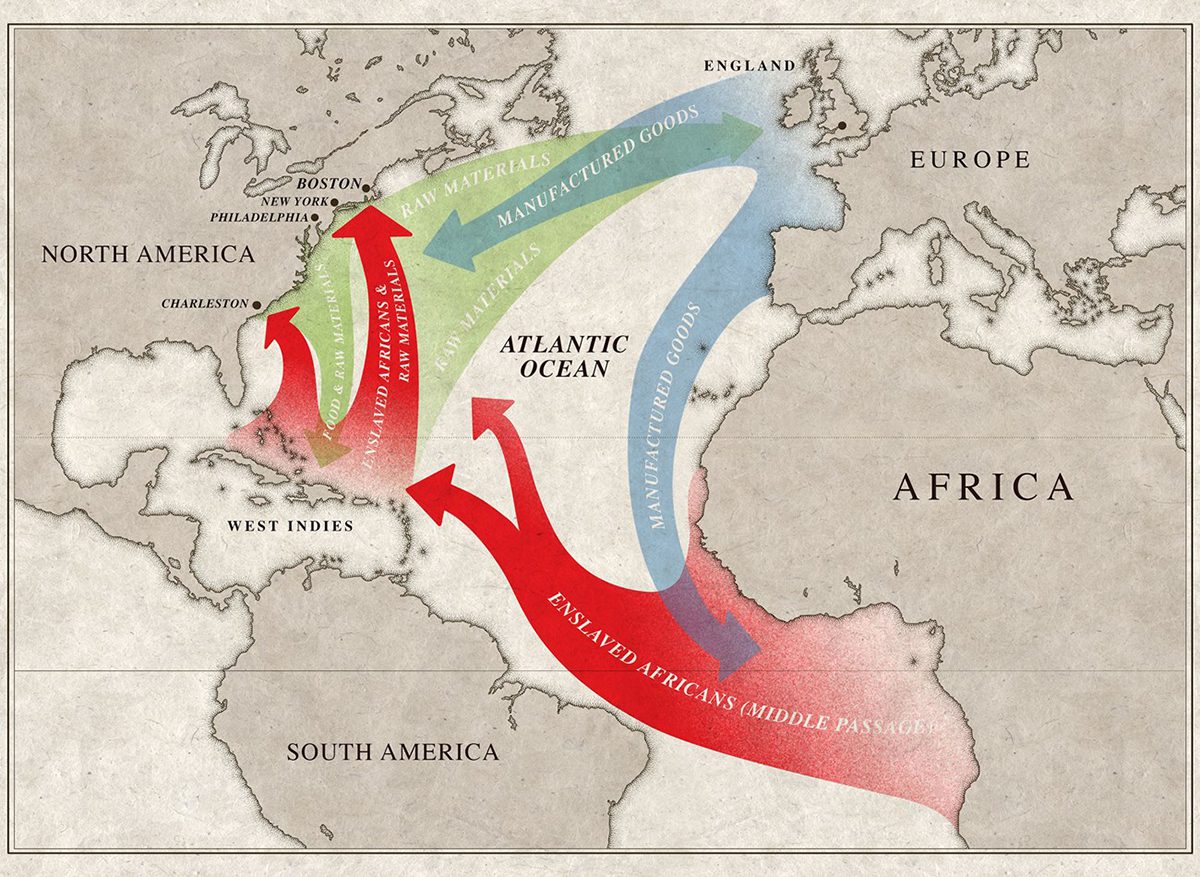

Middle Passage refers to the roughly 80-day voyage that was the middle part of the journey from Europe to West Africa, to the West Indies and North America, before the ships returned to Europe – the Triangle Trade. It’s when the vessels were packed with humans bound for slavery, and it was brutal and often deadly.

Heather Walker, executive director of the Eastern Carolina Foundation for Equity and Equality, is a subject matter expert and a research historian. Walker volunteers as an independent consultant and has worked closely with the National Park Service, North Carolina African American Heritage Commission, and the James City Historical Society.

“Roughly 12.5 million African people were forced to endure the brutality of the ocean voyage known as the Middle Passage,” Walker said.

She said that much like prisoners of war, when African nations would break out in conflict, people would be held by those rivals until either the conflict was over or they could be traded for one of their captured people.

“The Europeans took advantage of this and began to purchase these prisoners of war. And when there were none left to purchase, they began staging raids with rival African nations. And then they started kidnapping and selling those that they were able to capture. And this was all done in order to supply the Americas with an enslaved labor force, lowering their overhead,” Walker said.

She cited the words of African slave trader turned abolitionist and author of the hymn “Amazing Grace,” John Newton, who described unsanitary and horrid conditions aboard the vessels and how the captive Africans were stacked beside and on top of each other “like books upon a shelf,” and with insufficient food and water.

“Those who were forced to embark on the journey of the Middle Passage endured unimaginable cruelty in the form of physical, emotional and psychological torture,” Walker said. “This is evidenced by the following excerpt from an article in the North Carolina State Gazette, dated February 12, 1789. It says, ‘A young Negro woman, with her infant at her breast, was kidnapped away from her husband and parents and offered by the dealers in human flesh to this commander for sale. He was willing, he said, to purchase the young woman but could do nothing with the brat. However, as they could not be separated, he purchased them both at the same time, dashed out the brains of the infant on the deck of the ship, and threw it overboard in the mother’s presence. As she was a woman of uncommon beauty, in less than an hour, she was dragged by the captain to his bed and was forced to endure the embraces of her child’s murderer.’”

She said that about 2 million African people perished along the journey to the Americas, through acts of resistance and acts of violence such as this. “And although it’s commonly referred to as the Black Holocaust, the United States has yet to recognize the transatlantic human trade as a crime against humanity.”

Walker said that, like elsewhere in the Colonies, people in Portsmouth Village forcefully bred enslaved people and sold their children like cattle to turn a profit.

“It was the unpaid labor of those children that created wealth in this country. Enslaved people piloted these waters and lightered the ships at Ocracoke Inlet. It was their unpaid labor that made this a once-thriving maritime trade center. Enslaved people brought with them from Sierra Leone their knowledge and technique for making and mending fishing nets, a technique, mind you, that we still use here today. It was their unpaid labor that built and sustained our area’s fishing industry. Enslaved people worked these lands and built the settlements, some of those which we still call home. It was their unpaid labor that made survival possible,” she said.

She said that, sadly, a lot of the “bad stories” have been erased from history.

“But the real injustice here is that the good stories have been erased too. Those stories are gifts left to us by the ancestors. Those stories belong to us. Those stories are our stars of hope. Being deprived of these stories also deprives us of hope,” she said.

Walker said that from the foods we eat to the color we use to paint our porch ceilings, the traditions brought by enslaved Africans have become American traditions.

“Have you ever wondered why we hang ornaments on a tree, or why we bury our dead facing east? But for the strong, resilient and intelligent people who risked death to give us hope by smuggling rice seed and grain in the braids of their hair, we wouldn’t have okra or black-eyed peas, we wouldn’t have the sweet summertime treat that we call watermelon. But most importantly, we wouldn’t have hope,” she said.

Also during the ceremony Saturday, North Carolina native Rhonda Jones delivered the invocation, reciting a poem to the rhythm of attendees tapping together stones and seashells. The poem included the following verse:

In Your Honor, we stand on the island of Harkers, To place a permanent reminder of your arrival, With a marker. It is often said that we are our ancestors’ wildest dreams. It is your DNA that we carry, Deep within our genes. All Africans who came before and after the Hannah, It is you we celebrate. I call you to rise and take your place, As you elevate.

There is recent evidence that trauma and abuse, even when the details are lost to history or intentionally obscured, can leave a genetic imprint on future generations. Teel said that understanding history also means acknowledging how it has affected the descendants of enslaved Africans.

“Oftentimes, we wonder why African Americans are on the bottom of all the good lists and at the top of all the bad ones. And I’m here to tell you that part of it is because of the psychological trauma that is passed down through the generations and through the genes of those who come from enslaved people,” Jones said.

She said the lasting impacts of trauma are social and health related.

“And so you may wonder, why is hypertension and why is diabetes so high in the African American community? Well, oftentimes, it’s because we are still dealing with the impacts of those psychological traumas, and that has affected how our bodies actually respond to our environment today,” she said.

Understanding leads to empathy, she said, and that can lead to change.

“But that change requires time and understanding and the willingness to fight for what is right,” Teel said. “The question, when you leave here, that you must ask yourself as individuals is, are we willing to fight, are we willing to hold to the good fight, to stand up for what is right?”