On Feb. 21, 1918, the world’s last Carolina parakeet died at the Cincinnati Zoo in Ohio. The bird, named Incas, was preceded in death by his mate called Lady Jane.

At one time, the Carolina parakeet had a range that spanned the Midwest and the Southeastern Seaboard — including coastal North Carolina. Not actually a true parakeet but a parrot, its plumage was bright green with yellow and red on its head, making it quite a sight when these birds would fly together in flocks from tree to tree.

Supporter Spotlight

It was also what made their feathers such desirable adornments for women’s hats in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Called the “plume boom,” different species of colorful birds were hunted at unsustainable rates, contributing to drive some like the Carolina parakeet, the United States’ only native parrot, to extinction.

The plume boom led to the passing of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, one of the United States’ first federal laws geared toward conservation. It was part of a growing awareness that wildlife was not an unlimited resource. Acts like this paved the way for even more groundbreaking legislation, such as the 1973 Endangered Species Act, which turns 50 years old this year.

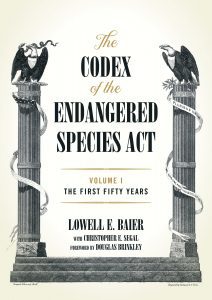

“The Codex of the Endangered Species Act: Volume 1, The First Fifty Years” is a more-than-700-page volume detailing the context for and first 50 years of one of the most pivotal pieces of wildlife legislation in the country’s history.

In this book, author Lowell E. Baier, an environmental attorney and historian, explains the pitfalls, the successes, the lawsuits and the collaborations that have defined this chapter of the act, and then offers an insightful look into what the future could be, all with the hope of preventing more casualties like the Carolina parakeet.

“There are many other species at risk, just like those that have gone extinct,” Baier said. “And if we lose those species which are protected by the Act, we will be forever remorseful.”

Supporter Spotlight

Context for the act and its first 50 years

Today’s understanding of conservation in the U.S. was largely informed by a realization that grew in the late 1800s that wildlife could disappear from the planet forever. During westward Colonial expansion, it became more clear than ever that wildlife was not simply an unlimited resource. The American bison, for example, once roamed the west in numbers of 50 to 60 million. After western expansion and colonization, those numbers would drop to fewer than 100.

As this and other predicaments became more apparent, momentum was starting to coalesce in elite hunting clubs and sporting publications. Game hunters had an understanding that some kind of legislation was needed to prevent widespread catastrophe. The first of these laws began emerging in the early 1900s.

The next several decades informed the need for widespread legal protection of species. The Endangered Species Act was preceded by legislation in 1966 and 1969 that didn’t achieve what lawmakers had hoped. When the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973, it was a threshold piece of legislation the likes of which and breadth of which had not been seen before.

Between 1973 and 2023, the Endangered Species Act would experience several notable growing pains. Though it has not seen any significant amendments since 1988, it has been a consistent source of tension between environmental groups and industry.

“When the ESA was first written and enforced, for the first 10 or 15, 20 years, it was very top-down in its approach to management of the species,” Baier said. This approach was largely informed by a militaristic mentality of protection through control. While the intention behind this was to save as many species as possible, one of the results of this approach was that the ESA was not made to be flexible over time.

“It was intended to be rigid,” Baier said. And as a result, the first 50 years of the endangered Species Act featured litigation and tension, but also evolutions and accomplishments.

Some of these issues and successes can be best understood by looking at wildlife issues in North Carolina.

Woodpeckers, Fort Bragg and the creation of Safe Harbor Agreements

The U.S. Army Fort Bragg base in North Carolina is situated in prime red-cockaded woodpecker habitat. In the 1990s, this interrupted military training substantially. In February 1990, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued an opinion citing that military training was posing a threat to red-cockaded woodpeckers on the base. For two years, training at Fort Bragg was severely abridged, causing units at the base to miss their training objectives in every way.

Ignoring the Fish and Wildlife Service opinion wasn’t an option — in 1992 at a base in Georgia, three Department of Defense employees were charged with harming red-cockaded woodpecker habitat, which carried with it lengthy prison sentences and fines of over half a million dollars. The charges were dropped, but it became clear that some kind of other compromise was necessary.

But as mentioned above, the Endangered Species Act was written to be rigid, not to compromise and it took about 20 years from its passing for the federal government to realize that the act would work better if it were more flexible. This transition was largely due to Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt under the Clinton administration. Babbitt came up with a 10-point plan to that end.

By 1995, a collaboration between Fish and Wildlife, the Department of Defense and the Environmental Defense Fund resulted in the creation of the first Safe Harbor Agreement, which is now an established tool used under the act. A Safe Harbor Agreement is an established plan that protects landowners from facing increased restrictions on their land as long as they fulfill agreed-upon requirements for preserving that habitat.

By 2017, there were 100 established Safe Harbor Agreements, and they have seen results. Those in the red-cockaded woodpecker’s habitat have resulted in a 20% increase in the bird’s population.

This new tool emerged because there was a need for it, but it hadn’t been written before. According to Baier, it is going to be very important for the future for the act to remain flexible to new ways to use it.

“I think it’s a great study that does demonstrate that humans can exist with species, provided that they give them room and don’t destroy their habitat,” Baier said. “It’s a wonderful example of how man has dealt with, in a very short period, a serious problem that engaged not only civilians but the military as well … That’s what really brought the military to recognize how much land they control that relates to species other than the cockaded woodpecker. And they become very, very involved in species conservation throughout America.”

Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, red wolf recovery

The eastern red wolf is a type of gray wolf whose historic range is in the Southeast. In 1967, these wolves were listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. In 1980, all remaining wild red wolves — only about 50 — were taken into captivity to increase the chance of species survival.

Over the years, eyes turned to the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in North Carolina as an ideal place to begin species reintroduction to the wild, and in 1987, eight wolves were released onto the refuge. This was pivotal because this was only the third 10(j) rule ever issued under the ESA — the 10(j) rule allows for the designation of listed species as “experimental,” so populations can be established outside of present range to support long-term recovery. The population grew to 130 wolves but then dropped back down to as few as 14 in recent years. Conflict over how to manage red wolves means that their future remains unclear.

Red wolves in North Carolina and Tennessee also led to an important court case in 2000: Gibbs v. Babbitt. Counties and private entities contested the federal government’s ability to restrict takes of red wolves on private lands. And the court ruled that this was a fair exercise of federal power under the Commerce Clause.

“The Commerce Clause has been widely used to extend the reach of the Endangered Species Act,” Baier said. “And red wolves are just one of the species that it has touched upon.”

The Next 50 Years

Both volumes of the “Codex” will be available for purchase in August. The second volume will focus on the things that Baier said will shape the next 50 years, until 2073.

“The link between the last 50 years and the next 50 years, the real key is twofold,” Baier said. “One is flexibility, and two is collaborative conservation — working together, rather than fighting.”

Flexibility, as shown by the creation of Safe Harbor Agreements in North Carolina, will be necessary to keep the Endangered Species Act relevant and working towards collective goals. Collaborative conservation is the idea that the most successful conservation occurs when issues are addressed holistically — when environmentalists, regulators, people who work the land, and all other interested groups can come together and figure out solutions.

Moreover, as a society, we have to overcome what Baier calls “shifting baseline syndrome.” In other words, people’s metric for how urgent an environmental is can only be compared to what they already know. For those today who never got a chance to see the Carolina parakeet, now over 100 years gone, it’s hard to react with urgency to what we don’t even realize we’ve lost.

A lot of the solutions to these issues have got to start at the local level, Baier said. With local conversations and local problem-solving about local issues.

“When enough of that occurs, perhaps America will wake up again.”