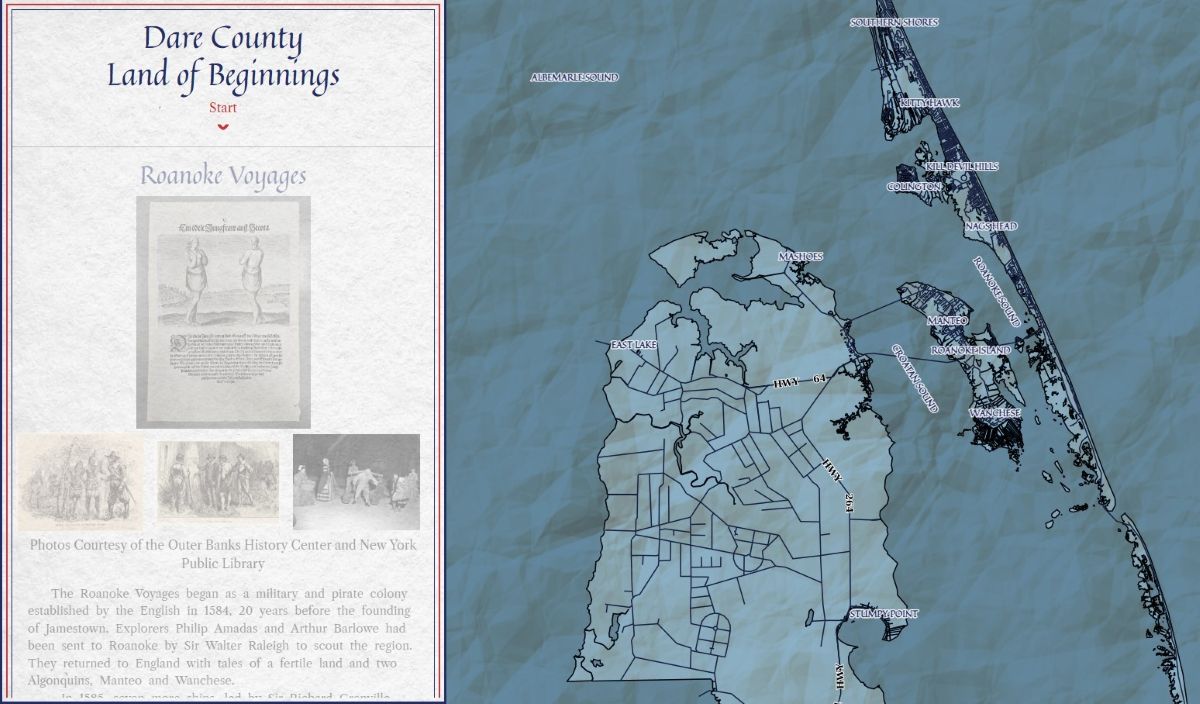

Second of two parts. Read part 1.

Reading a history book as an undergraduate student, a northeastern North Carolina woman paused, surprised — “Well, there’s my grandfather.”

Supporter Spotlight

Ramona Brown, now 61, was in a history class at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, working toward her degree in journalism, a field in which she’s worked for 40 years.

She was learning about the turbulent school integrations in Charlotte during the Civil Rights era.

“And that’s when I discovered this story out of Hyde County,” Brown said. “I shared it with my mom and she said, ‘Oh yeah, I was a part of that, along with your granddaddy.’”

Her grandfather, Golden Mackey, was quoted in David S. Cecelski’s 1994 book, “Along Freedom Road.” He was an alumnus of one of Hyde County’s two Black schools, both of which officials planned to permanently close in the process of integration.

Brown was 7 and 8 during the 1968-69 school year, when Black and Native American parents in Hyde County carried out one of the longest and most successful Civil Rights protests in the country, spurred by their disagreement with this school desegregation plan. They didn’t send their children to school that year, held nonviolent protests daily for months, marched on Raleigh twice and rid the county of the Ku Klux Klan with a gunfight, as Cecelski details in the book.

Supporter Spotlight

Seeing her grandfather’s name in print prompted Brown’s interest in genealogy and a desire to seek more information out about that time, which she remembered, but hadn’t fully understood as a child.

She recalled her grandfather hosting community meetings along with other ministers, sometimes in homes but “principally at the quote-unquote ‘Black’ churches at the time,” where they discussed strategies for approaching the school board and government officials “to integrate the schools in a way that was not racially infused.”

Her mother, Ethel Mackey Brown, served as a secretary for the meetings.

Throughout the South, whites persistently fought against school desegregation, sometimes violently. “The depth of white resistance to sending their children to historically black schools was also reflected in the flames of the dozens of these schools that were put to the torch as desegregation approached,” Cecelski wrote.

And when it happened, desegregation was a one-way street: Surviving former Black schools were almost always shuttered; Black and Native American teachers and principals were fired en masse; Black and Native American students were sent to white schools; and only white teaching styles and school cultures were preserved.

An entire generation of Black principals were “eliminated,” Cecelski wrote. And North Carolina was second only to Texas in the number of Black teachers who lost their jobs.

“By 1966 and 1967, few black communities failed to raise objections to school closings and teacher displacement,” he wrote. But while other communities in the state had protested, “one of the strongest and most successful protests, the first to draw national attention to the problem, occurred in one of the South’s most remote and least populated counties.”

Hyde County’s community of people of color didn’t want to sacrifice everything for integration. They organized and they committed fully for the long haul.

The meetings centered on “how to successfully integrate the schools so that the people of color don’t feel like they’ve lost all of their traditions and their cultures … and how Caucasians don’t feel this is a bad thing and that they’re losing as well,” Brown explained.

Brown prefers the term “people of color” because, as she learned from her grandfather, her family has not only African descent but deep Indigenous roots as well.

Golden Mackey’s children were all adults at the time, “but he was such a proponent of education, he got involved in it,” Brown said. He took part at the marches at the state legislature, but she didn’t know of any involvement in the gunfight.

Mackey was involved with the “Star of Zion Church of Christ, Disciples of Christ,” which his father had helped found. As Cecelski’s book notes, the church community was intimately involved in not only the organizing and sustaining the peaceful protests, but also in supporting the children’s education while they were out of school.

That echoed earlier school history in the county.

“Before there was public education for all children in Hyde County, there were parochial schools there,” Brown said. “This particular church — my great-grandfather Benjamin Mackey was the superintendent and founder of that school there for children of Native American descent and African descent.”

The protesters prevailed despite enormous challenges.

North Carolina’s government officials would prove to be the best in the South at subverting the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

“White politicians in North Carolina opposed school integration with the same conviction as their counterparts in other southern states, and with more acumen,” Cecelski wrote. “In the spring of 1955, the General Assembly resolved that ‘the mixing of the races in the public schools … cannot be accomplished and should not be attempted.’”

To that end, state politicians “engineered a series of legal and administrative barriers to school integration that, although very effective, did not appear openly to defy the Supreme Court.”

The Pupil Assignment Act and the Pearsall Plan were two such measures. They shielded the local education boards from potential lawsuits, allowing North Carolina to avoid school desegregation for more than a decade after Brown v. Board of Education — “longer than many school districts in the Deep South and Virginia where militant resistance to school desegregation had occurred,” Cecelski wrote.

And by fall 1967, Hyde County was an outlier in the state, with just three Black students attending classes with white students — the lowest biracial school enrollment in the state.

Not only was white resistance to integration constant, but Black students felt uncomfortable in the white schools. They missed their Black teachers and principals who had served as “their most important role models and counselors,” and they missed the high expectations and family-like school atmosphere they were used to, Cecelski wrote.

Students encountered racism from classmates, teachers and administrators, and their parents experienced harassment that included death threats and intimidating messages from the KKK, as Cecelski detailed.

After years of protests, negotiations and federal pressure, as Cecelski wrote, by the end of the 1969-70 school year, Hyde County officials agreed to keep both the Black schools, O.A. Peay and Davis, open.

That alone was a remarkable victory in the South, but there were more. Among other agreements, officials decided to keep both the Black schools’ principals; preserve the teachers’ jobs; hire a Black assistant principal at the historically white Mattamuskeet School; start an African American history class; keep former educator and principal O.A. Peay’s name on that school; and allow use of all three of those schools for the Founder’s Day and the Homecoming celebrations that had played a big role in Black school and community culture for years.

“These were, in the end, the ultimate successes of the Hyde County school boycott,” Cecelski concluded.

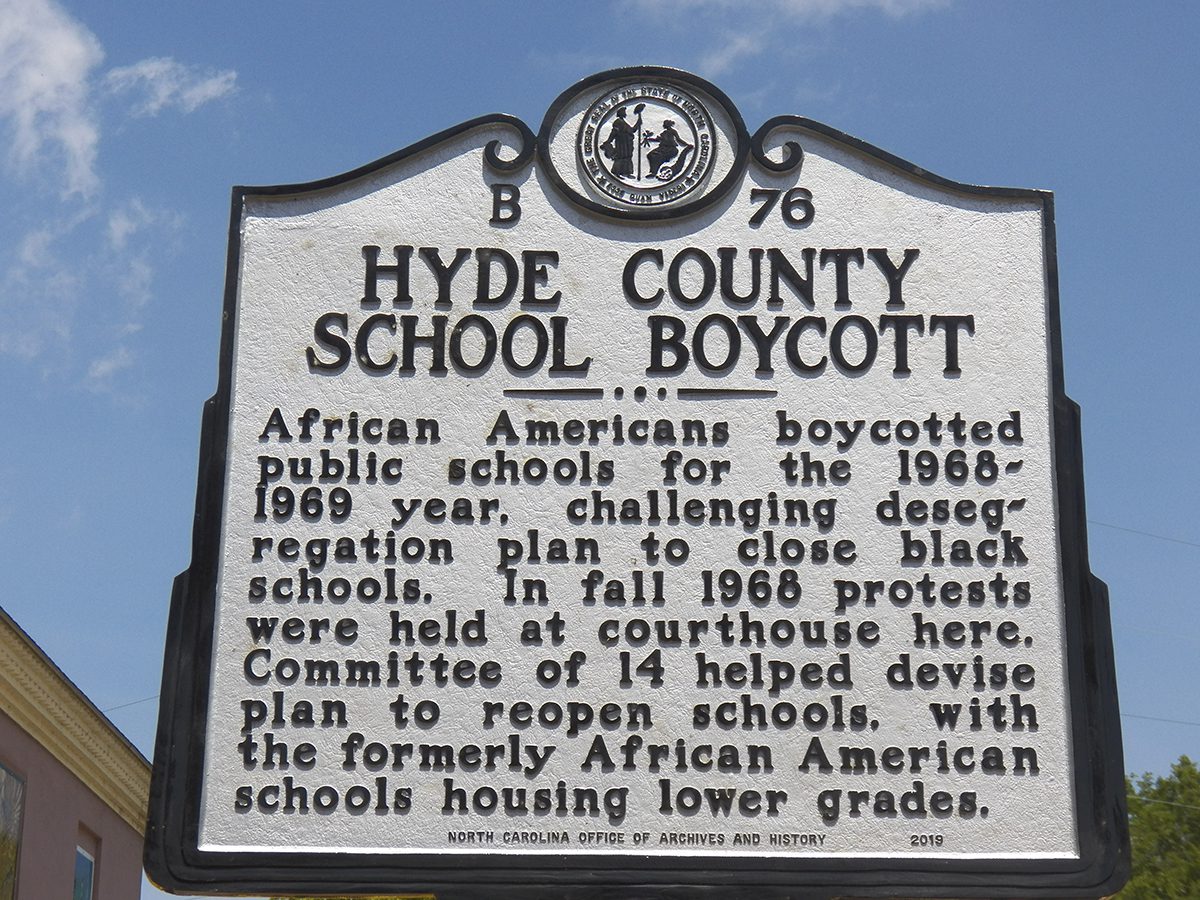

The North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program cast a marker in 2018 to denote the historical significance of the event. The marker was formally dedicated in May 2019, with Alice Spencer Mackey, a student during the time of the protest, in attendance, according to the Ocracoke Observer.

To read more about the marker, visit http://www.ncmarkers.com/Markers.aspx?MarkerId=B-76.