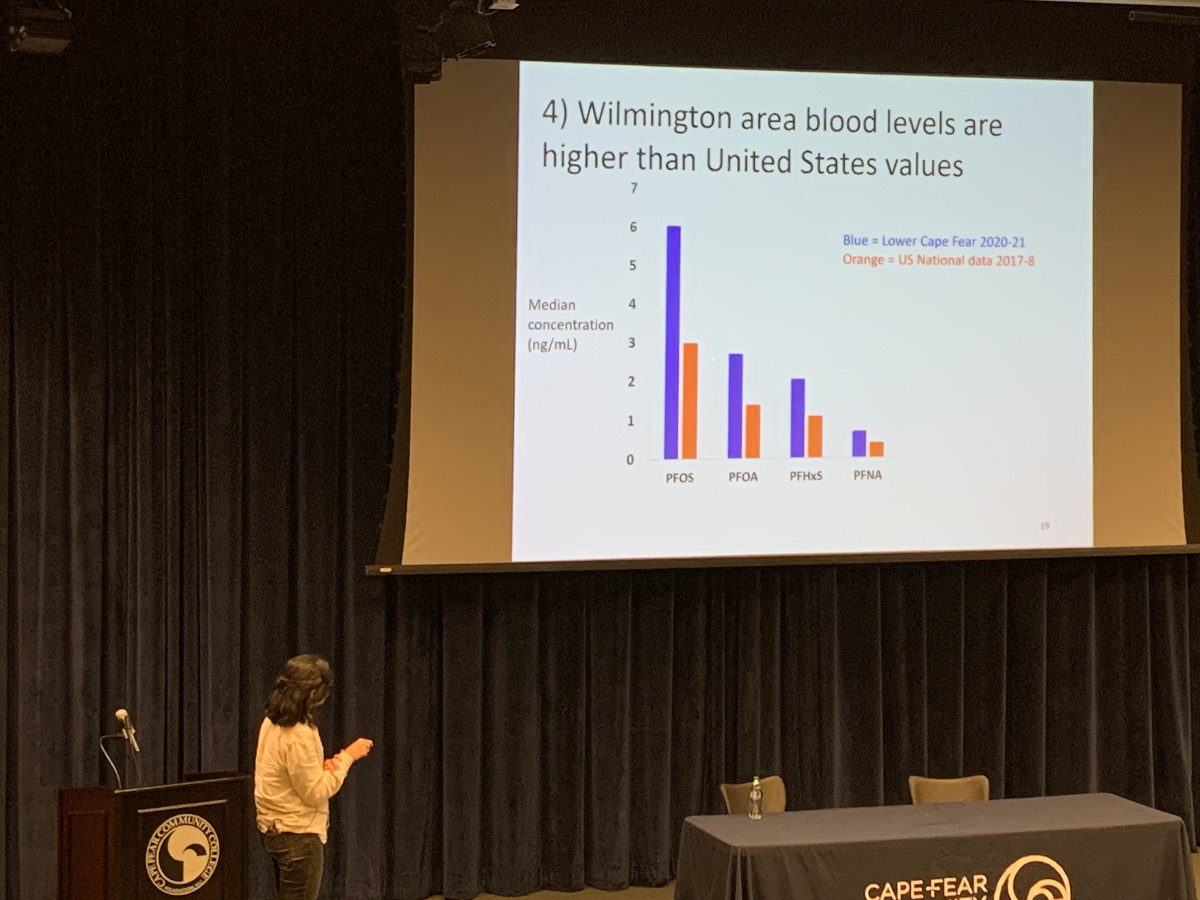

WILMINGTON – Many people living in the Cape Fear River basin who volunteered to take part in the most recent GenX exposure study had higher levels of four highly fluorinated compounds in their blood than the average American.

While GenX was not found in the blood samples of 1,020 residents in Wilmington, Fayetteville and Pittsboro, three per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, unique to the Chemours Fayetteville Works facility were in the blood of almost everyone who participated in the 2020-2021 study.

Supporter Spotlight

The results of this latest GenX exposure study were discussed Wednesday evening during a public meeting hosted by Cape Fear River Watch in Cape Fear Community College’s Union Station.

Researchers with the North Carolina State University Center for Human Health and the Environment were quick to point out that while GenX was not found in blood samples, that does not mean people were not exposed to the chemical compound. That merely suggests GenX does not last in the blood for a long time.

PFAS found in blood samples from Wilmington-area residents were the same as those found in samples taken from residents who participated in the initial 2017-18 study.

Nearly everyone who participated in the study had perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, or PFOS, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid, or PFHxS, and perfluoronanoic acid, or PFNA.

Those synthetic chemicals get into the Cape Fear River from several different sources, including textile and furniture manufacturers, sludge from wastewater treatment plants used as fertilizer, and firefighting foams used at airports, according to researchers who conducted the study.

Supporter Spotlight

Chemical compounds unique to Chemours – Nafion byproduct 2, and perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids PFO4DA and PFO5DoA – were found in the blood of almost everyone from the Wilmington-area region who participated in the first GenX exposure study in 2017-18.

Nadine Kotlarz, a research scholar at N.C. State, said Nafion byproduct 2 was found in 422 out of 514 Wilmington-area residents who participated in the 2020-21 study.

Blood samples of 433 of those residents also contained PFO5DoA.

Kotlarz explained that researchers went back and reanalyzed the original blood samples collected in the 2017-18 study after new commercial testing standards were established. The results revealed the people found to have PFO5DoA in their blood had higher concentrations than originally detected.

“To date there’s little known about the toxicity of this PFAS,” Kotlarz said.

Jamie DeWitt, a professor at East Carolina University, studies the immunotoxicological and developmental immunotoxicological effects of PFAS.

Next month, she and her team will redo a study of the effects of PFO5DoA in lab mice after discovering in a first go-round of testing that mice dosed at the highest level, 50 milligrams per kilograms of weight, simply could not handle that much in their systems.

“In mice this compound appears to be quite toxic,” DeWitt said Wednesday. “We don’t know if it will affect people in the same way. From my perspective, it’s a problem if it’s a problem in mice we need to study whether it’s also a problem in people.”

Potential health effects of an overwhelming majority of PFAS – there are upwards of 10,000 individual PFAS – have not been studied.

Health studies on legacy PFAS, such as PFOS, PFOA and PFHxS, show those chemicals can decrease antibody response to vaccines; lead to dyslipidemia, or elevated cholesterol, which can lead to cardiovascular disease; decrease infant and fetal growth; and increase the risk of kidney cancer.

Commercial production of PFAS began in the 1940s. They are resistant to heat, water and grease and they are used in a host of consumer products, including carpets, carpet cleaning products, food packaging, furnishings, cosmetics, outdoor gear, clothing, adhesives and sealants, firefighting foam and nonstick cookware.

During a question-and-answer session Wednesday, Jane Hoppin, principal investigator of the GenX exposure study and professor at N.C. State, said there is no good way individuals can reduce all of the ways humans are exposed to PFAS.

“There’s many PFAS in our everyday lives,” she said.

The most effective way to reduce exposure is by removing PFAS from manufacturing.

Chemours Fayetteville Works facility, some 75 miles upstream of the Cape Fear River from Wilmington, uses GenX as a replacement for PFOA for manufacturing fluoropolymers such as Teflon. PFOA was voluntarily phased out of production more than 10 years ago in the U.S.

In 2017, a then-freelance journalist in Wilmington broke the news that Chemours had been discharging PFAS into the Cape Fear since 1980.

Since then, Chemours has been required, as part of a 2019 consent order with the state and Cape Fear River Watch, to drastically reduce its emissions of PFAS into the river, the ground and the air.

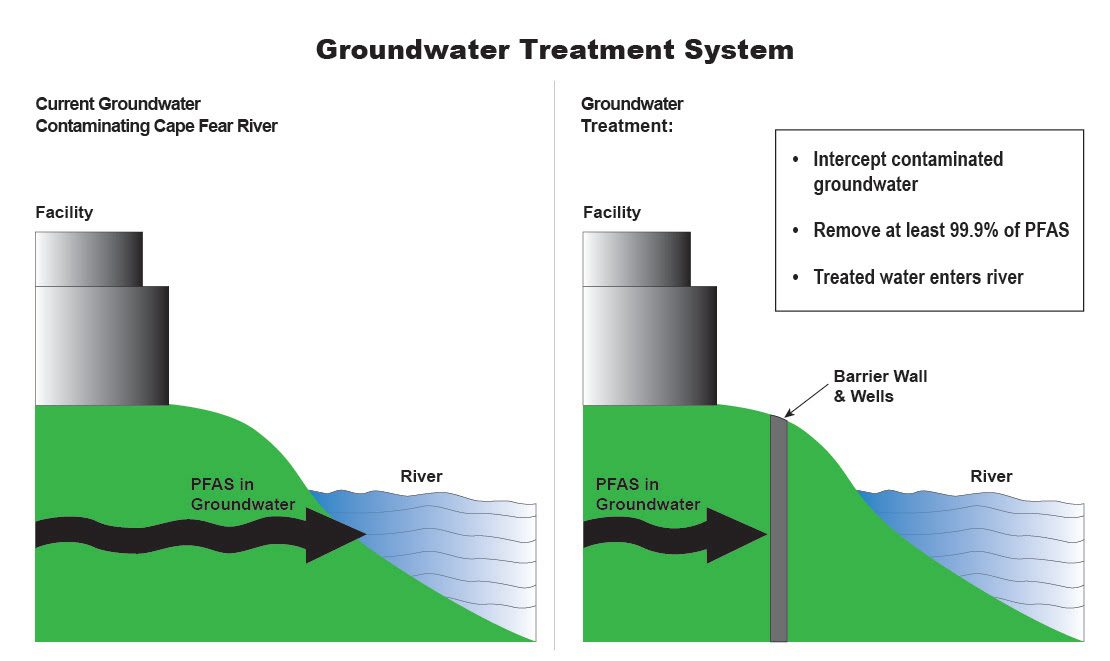

Chemours, a DuPont spinoff, has plans to build a massive underground retaining wall to stop the flow of PFAS in ground water at the plant from entering the river.

As part of the consent agreement, Chemours has been testing private water wells, including those in the lower Cape Fear region, for contamination. The company must provide a means of uncontaminated drinking water to households with private wells that contain higher levels of PFAS.

Six North Carolina community and environmental justice groups, including Cape Fear River Watch, are suing the Environmental Protection Agency to require Chemours to pay for health studies on 54 PFAS.