Dec. 1, 1922, was an overcast day with a strong wind from the south in New Bern. It was the day after Thanksgiving — it was not until 1942 that the holiday became the fourth Thursday of the month.

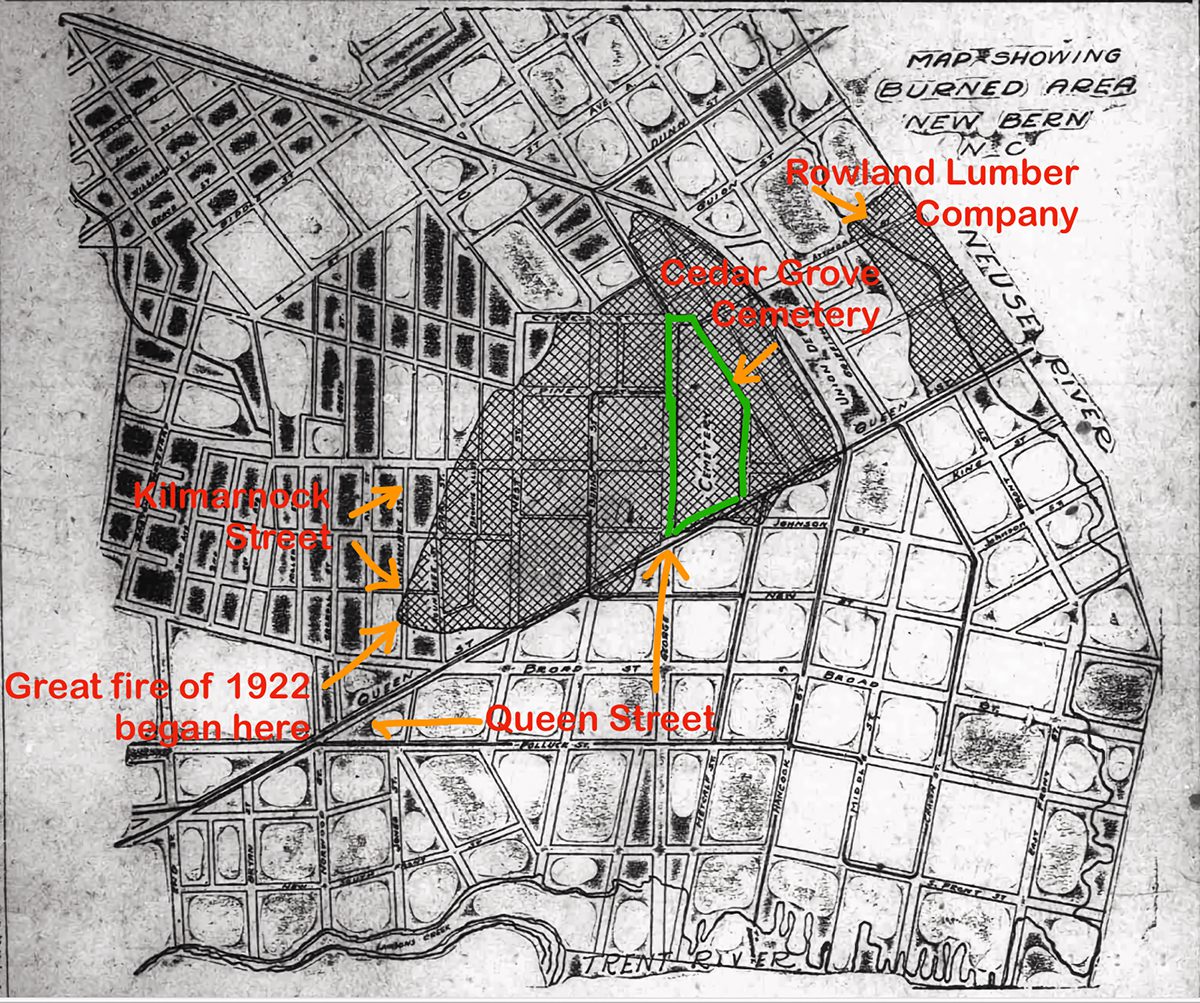

Also, it was the day a quarter of the city went up in flames. A fire that, according to New Bern historian Bill Hand, is still the largest urban fire in North Carolina history.

Supporter Spotlight

For most of the residents of the city it was a workday, although hundreds were in Raleigh to cheer the high school football team on to victory in the state tournament.

At the time, lumber and wood product factories were some of the city’s biggest employers, and along the Neuse River, sawmills lined the riverfront.

Sometime around 8 a.m. the Morning New Bernian reported in its Dec. 2, 1922, edition that a fire had begun at the largest facility in the city, the Rowland Lumber Co., and quickly engulfed the business.

“The blaze is said to have originated from friction caused by a belt on the leg jack in the saw mill building. This was discovered shortly after it had originated but the spread of the flames was so rapid that before an alarm could be sounded and water gotten to the fire, the building was a mass of flames,” the newspaper reported.

The Rowland Lumber Co. fire was the beginning of a series of seemingly unconnected coincidences that led to an estimated 900 to 1,000 structures destroyed, leaving as many as 3,000 people homeless.

Supporter Spotlight

At the time, there were two volunteer fire companies protecting the city: the Atlantic Fire Co. and the Button Co. There was tremendous rivalry between the companies and in hope of toning down the competition, the city decreed that the chief of each company would alternate odd and even years as the city fire chief.

“So, we know that the chief on the day the fire was actually the chief of the Atlantic Volunteer Fire Company as well,” Pat Dunleavy, a volunteer at the New Bern Firehouse Museum said during a recent presentation at the firehouse.

Both companies responded to the fire, and Atlantic Chief James Bryan decided to keep his company on hand and send the Button Company home.

“The standard practice at the time was that if the chief decided he didn’t really have to have both companies, they’d send one back to their fire station in case there was another fire alarm,” Dunleavy explained.

Around 9 a.m., an alarm came in for a fire at a home in the city’s housing area for Black residents.

Chief Bryan left the Rowland Mills fire and after arriving on the scene, found that the residents had formed a bucket brigade and extinguished the flames themselves.

An hour later, a third alarm sounded at Kilmarnock Street.

“The chief breaks away, comes down to take a look and discovers that it’s not a single house fire, but three houses have already burned down and three blocks of houses are on fire,” Dunleavy said.

Bryan faces a dilemma. Unlike the white sections of the city, the Black neighborhoods do not have municipal water. In 1922, “If you were Black living in this area and you wanted to get water you (would) send your kid outside with a bucket to go to the hand pump and get a bucket of water.”

The lack of water pressure and the rapidly spreading flames were not the only problem the chief faced. There was also a critical shortage of trained personnel.

“New Bern High School was on their way to the state championship. Over 300 people loaded the train and others drove to Raleigh that morning,” New Bern historian Carol Becton noted during a lecture she delivered earlier this month at Tryon Palace.

Numerous accounts estimate the wind at 30-40 mph with stronger gusts. Around the periphery of the Black neighborhoods, the fire companies had the water pressure they needed to keep the fire from spreading to the white homes, but their fire trucks had neither the capacity in their tanks nor the water pressure to battle the blaze. Bryan had his two companies, but neither was at full strength, with quite a few firemen in Raleigh for the big football game.

And there was one more factor, perhaps the most significant of all.

“These houses are almost all wood construction. Almost all have cedar shake shingle roofs, the whole building was just a fire waiting to happen,” Dunleavy said.

The chief saw the fire burning out of control, realized the wooden homes were tinder and made a drastic decision. The only course of action, he determined, was to create a fire break.

“So, he decides he’s going to blow up all these houses on Queen Street (on the south side of flames) to remove the fuel from the air,” Dunleavy said. “Of course, that won’t really remove the fuel. What it will do is lower the fuel so the sparks will be not so easily blow onto the roofs.”

The firemen waste no time in placing either dynamite or gunpowder under homes, though newspaper accounts differ on which explosive it was. The firemen were moving so quickly they may have endangered lives.

The Coast Guard Cutter Pamlico’s homeport was New Bern and as the fire spread, crewmen from the ship came to help.

In his book “New Bern History 101,” Edward Barnes Ellis Jr. tells of Coast Guard officer William Montague who entered a house to help a woman out as the firemen were getting ready to blow it up.

“With the woman in his arms, Montague saw three men placing explosive charges. He shouted to tell them he was in the building (but) to no avail. The blast blew Montague and the woman through a wall and into the yard,” he wrote.

Montague was unconscious for several hours, but other than that he and the woman suffered only minor injuries.

The fire, according to the New Bernian, had originated in the home of Henry Bryan, a Black itinerant barber on Kilmarnock Street, in the section of the city occupied mainly by Black residents.

Whether the Bryan house was the first to catch fire may be difficult to determine. It was certainly one of the first, and Hand, the historian, had an opportunity to interview Dr. Samuel Bryan who was 4 at the time in 1922.

“He was a child in that house on Kilmarnock Street and remembered sitting there. Everybody runs out and he’s still sitting at the table eating his breakfast, which is Thanksgiving leftovers, and they had come back in and drag him out,” Hand said.

Bryan, a dentist, died in 2014.

The firebreak does little if anything to stop the spread of the flames, and the chief realizes he has neither the resources nor personnel to fight the fire.

“He starts calling neighboring towns to ask for assistance,” Dunleavy said. “Kinston 35 miles west says yes, they’ll send a fire company and a fire truck down, but they have to travel over 35 miles across the (dirt and gravel) roads to get here. So it’s not going to be quick. Little Washington responds and says yes, they’ll send the fire truck in there. But they have to wait and get a flatbed railroad car.”

Washington firefighters do not arrive until 3 p.m., and Kinston makes it to the fire an hour later.

In the Black neighborhoods, people are grabbing what they can from their homes and fleeing for their lives. Many of them retreat to the Cedar Grove Cemetery. With its stone walls and open green space, the cemetery nearest the southeast side of the area that burned became the overnight refuge for hundreds if not thousands of residents.

They often arrived with flames hard on their heels. In “The Great Fire of New Bern of 1922,” a compilation of oral histories gathered in 1992 by the Memories of New Bern Committee, Joe Gaskill McDaniel recalls running for his life with a friend.

“Frank and I were standing in a patch of collards growing in a vacant lot across the street. Wind caught the flames on the roof and carried them across the street. We fled from their path and you could hear the collards crackling as the fire consumed (them),” he said.

It was not until late afternoon or early evening that the fire was finally brought under control.

What greeted New Bern residents the next day was a scene of unimaginable destruction. Block upon block of charred wood, some smoldering, with the brick chimneys still standing to mark where homes had stood.

Yet there was only one reported fatality, Harriet Reeves, purportedly 105 years old and born into slavery. Exactly what happened is unclear. Some reports cite her weakened condition and an inability to escape. Others say she was escorted from her home, but went back to get personal belongings and was overcome by smoke.

The misery from the fire did not end Dec. 1, 1992. One quarter of the population of the city was now homeless, in many cases with only the clothes on their backs.

Help begins to arrive almost immediately.

“In the days following, Fort Bragg sent eight freight cars of tents, cots and mattresses, and other equipment for the homeless, with other organizations contributing clothing, money, and food to assist. A temporary ‘Tent City’ was established in Cedar Grove and at the Greenwood Cemetery for the homeless …” Nancy Figiel wrote earlier this year for Yes! Weekly.

Each family was issued two tents; one for sleeping and the other as a common area for cooking and gathering.

In “The Great Fire of New Bern of 1922” oral history, Mary Barden points to another tragedy.

“Losses were estimated at two and a half million dollars and about a third of this was covered by insurance,” she said, a figure that is consistent with newspaper accounts of the time.

Retired schoolteacher Dorcas Carter recalls in the oral histories what the aftermath was like.

“The town has changed, because three thousand people were left homeless, and out of this they became quite disheartened,” she said. “No jobs, property condemned …”

It was the condemnation of the properties by the city that for many Black residents created a bitter legacy. Rather than allow all the homes to be rebuilt, New Bern used the opportunity to create city parks, widen streets and create government buildings.

“They did not allow the blacks to rebuild on their home site … This was upsetting … not returning to your birthplace,” Carter said, and described in detail what would happen when someone would try to rebuild.

“I’m recalling now a nearby neighbor who was a Mr. Richard Sawyer … attempted to rebuild. His homesite was on the condemned section … Each time he would get his frames up the city would make him tear it down. Finally he built up to the second story ready for a roof … He was ordered to tear down,” she recalled.

Becton in her lecture described how confusing it would have been for the residents of the area, showing a notice that read: “All owners of property located in the area that has been condemned by the by the Board of Alderman of the city of New Bern or parks, cemeteries and playgrounds and extensions and widening of streets would please file their claims with the City Clerk of the city of New Bern at the city hall at once in order that claims may be paid, adjusted and settled by the board of appraisals”

For many of the homeowners in those neighborhoods at that time, Becton explained, the notice was like a foreign language.

“Keep in mind, this is segregation, Jim Crow, and a lot of people may not be able to read well or at all or understand a lot of the terminology and were not even able perhaps to execute some of the requirements,” she said.

The loss of homes and property were not the only troubles confronting the Black community of the city.

“When the Rowland Lumber Company closed, many people were left unemployed. As a result many moved North,” Mary Chapman was recorded as saying in the “Great Fire” oral history.

“The demographics of the city before the fire was 60-65% Black with 35-40% of white population after the closing of tent city — all those Black people leave,” said Dunleavy. “There’s no choice. They need to get jobs.”

U.S. Census estimates show a shift to 55.6% white, 33.1% Black.

Becton, in her lecture, focused on more than the horror of the fire, also calling attention to a community hospital for the Black residents and a library that became a part of the community. Pointing to a mural that had been painted on the side of a building on Queen Street that depicted a Phoenix flying above a burned-out city, she described it as representing how the community recovered.

It was, as she recounted it, a “Phoenix rising out of the ashes. And so that’s exactly what happened for those victims of the great fire.”