The Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Resources is to continue work on a submerged aquatic vegetation water clarity standard, members of the Environmental Management Commission’s water quality committee unanimously decided during its recent meeting.

Establishing a water clarity standard, which is a type of water quality standard, is one of several recommendations in an effort to preserve and protect seagrasses, a critical coastal habitat, in the 2021 amendment to the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan. Water clarity measures the amount of sunlight that can penetrate through the water. Submerged aquatic vegetation, often called SAV or seagrasses, need light to grow.

Supporter Spotlight

“The major cause of SAV loss has been due to water quality degradation from nutrients and sediments, which reduce light penetration needed for grass survival. A series of steps to improve water clarity are required,” according to the protection plan, a long-term, state-managed effort to improve coastal fisheries through habitat protection and enhancement work. “Nationally, water quality, in particular water clarity, is recognized as one of the most significant factors limiting SAV distribution, abundance, survival, and expansion.”

The recommendation in the protection plan states that by 2022, the Environmental Management Commission will receive guidance from the Nutrient Criteria Development Plan Scientific Advisory Council on establishing a water quality standard for light penetration, with a target value of 22% to the deep edge, or 1.7 meters, for all high-salinity seagrasses, and a light penetration target of 13% to the deep edge, or 1.5 meters, for all low-salinity seagrasses.

The North Carolina Nutrient Criteria Development Plan Scientific Advisory Council provides advice and recommendations to the state Division of Water Resources on site-specific nutrient criteria based only on data and scientific judgments about pollutant concentrations and their effects.

During the Environmental Management Commission’s water quality committee meeting Nov. 9, Commissioner Marion Deerhake, who chairs the committee, explained to fellow board members that setting a water clarity standard is the first step before the division can proceed with drafting rules to implement the standard.

The standard is to be based on the completed work of the Science Advisory Council, expected in the next few months, as well as the input of the Criteria Implementation Committee before the draft rule is presented to the Water Quality Committee, Deerhake said. The Criteria Implementation Committee is an advisory board of stakeholders that are to look at the practicality of implementing the standard.

Supporter Spotlight

After the commission approves a draft rule on water clarity standard, an extensive stakeholder process will follow, then the development of Implementation rules to apply that standard, she explained.

Deerhake asked that it be noted in the meeting minutes that the water quality committee members reached a consensus that the division is to continue working on water clarity standards for seagrasses.

Dr. Jessie Jarvis, an associate professor in the biology department at University of North Carolina Wilmington and Scientific Advisory Council member, explained to the committee that seagrasses have a lot of different roles in the coastal ecosystem.

Seagrasses serve as important and essential habitat for commercial and recreational fisheries, are a direct resource for marine herbivores like sea turtles, and as waters are warming, more fish are eating seagrass directly, she continued. These underwater plants are really important because they actually improve the water quality conditions. They help increase clarity, reduce sediments and nutrients, and can store carbon.

“There’s a lot of functions that they do, so keeping them around is a really good way to keep those functions happening. It’s also a lot cheaper to protect them than it is to actually restore them,” she explained.

Jarvis said that before a standard can be set, you have to look at the minimum amount of light that seagrasses need to survive, which can be calculated based on the maximum depth at which they grow, and then how much light is available at that depth.

“We have to assume that the light at the depth that they grow the deepest is the minimum amount of light they require. And then from that we can calculate any minimum light required for them to survive any particular depth,” she said. Adding, if you have light attenuation and the maximum depth, you can determine what percent SAV actually need to survive at any depth.

“One of the reasons that we’re so focused on clarity when it comes to SAV is they are found in the water column,” and there’s lots of other things that could potentially impact these seagrasses such as changes to salinity or dissolved oxygen. “But when you look at how much light SAV actually need to survive, it’s really high compared to other plants and even other marine plants,” Jarvis said.

Seagrass require from 4 to 29% of the surface light to survive. Terrestrial plants only need .5 to 2%. The seagrass, even at its lowest light level, needs twice as much light of a terrestrial plant. The majority of plants, including those in most of estuarine systems, require closer to 20%. Comparing terrestrial plants and marine plants, seagrass really require a lot of light.

“They have a very high minimum light requirement, and so their survival really depends on good water clarity. If you have good water clarity, they are much more likely to be able to withstand any other kind of disturbance,” she said.

Noting this link between water quality and seagrass led to researchers to establish the submerged aquatic vegetation as a sentinel species for water quality changes. Seagrasses react to water quality changes like other sentinel species such as oysters. But seagrass also need light. So, in addition to those chemical parameters that affect other underwater sentinel species, seagrasses also respond to changes in water clarity.

Another benefit for using SAV as an indicator of water quality is that they’re not harvested, Jarvis said. If there’s a change in seagrasses to any extent that you’re measuring, the changes can be primarily, directly linked to changes in environmental conditions only.

“In North Carolina, we are lucky enough to have the Coastal Habitat Protection Plan with a very strong recommendation to adopt a standard for light penetration for seagrass regions based on that low and high salinity breakdown,” she said. “So low salinity would be 13% to the deep edge which they defined in the CHPP as 1.5 meters and high salinity 22% to the edge of 1.7, based on a lot of the information that went into that, and again, the robustness and the really good repeatability of these measurements in July and September the Nutrient Criteria Development Plan Scientific Advisory Committee that supported the adoption of both the low and high standards.”

Jarvis explained that she worked with the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, which mapped the entire Albemarle-Pamlico Sound in 2007 and 2013, and smaller segments in 2020.

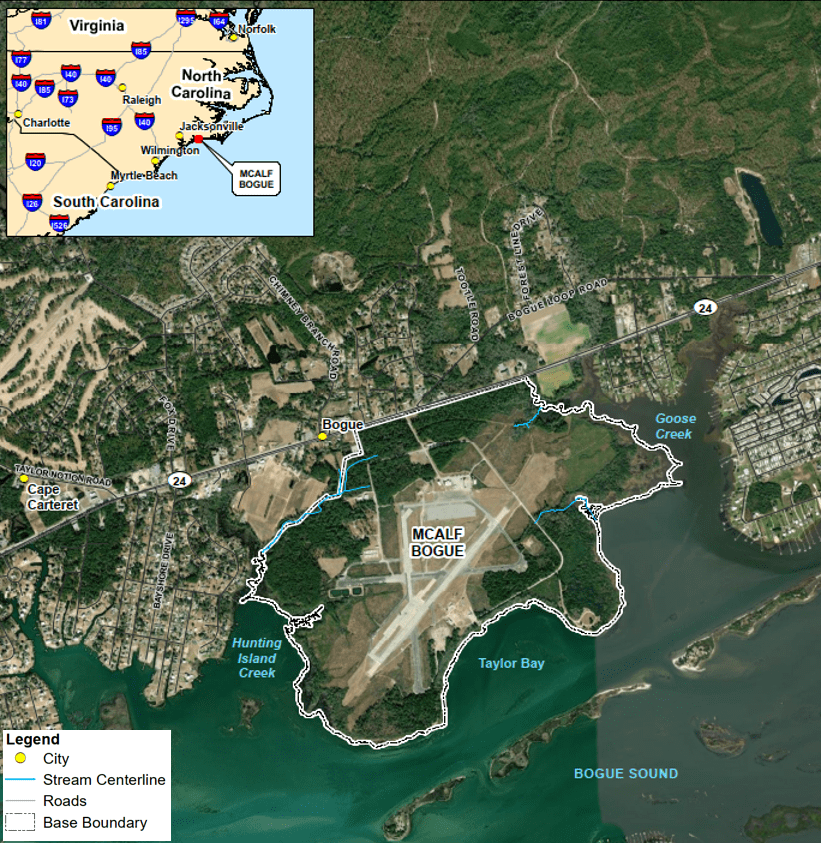

“What we found is that overall SAV in North Carolina is declining at about a rate of about 5% of total area per year. Now that’s not the same everywhere. So, there are some problems areas for example, back in Bogue Sound that rate of loss is closer to 10%. And there are definitely areas where you could actually see these changes in SAV,” she said.

Karen Higgins, chief planning section for Division of Water Resources, also addressed the committee. She said told the members that the Nutrient Criteria Development Plan, or NCDP, is a plan for developing nutrient criteria for surface waters in North Carolina. The plan is required as part of a memorandum of understanding with the Environmental Protection Agency.

The plan was first developed in 2014 and 2019. Anytime the state updates the plan, it has to be reviewed and approved by EPA. North Carolina has approached the plan by having site-specific standards in three different types of water bodies. These are lakes and reservoirs, estuaries, and rivers and streams. The first site-specific standard was for High Rock Lake in Davidson and Rowan counties. Environmental Management Commission approved a site-specific standard for High Rock Lake earlier this year.

Right now, the scientific advisory committee is focused on Albemarle Sound and the Chowan River, in particular with seagrasses, Higgins continued. Clarity is critically important for submerged aquatic vegetation. The Scientific Advisory Council has been working with the division over the last year and a half looking at different components of the clarity standard.

The Division of Water Resources, Coastal Habitat Protection Plan and the Scientific Advisory Council are all on board with a magnitude value that is projected for seagrasses habitat. The council has also determined the duration, or when the standard applies, but there are some other pieces still under discussion such as frequency.

While the focus has been Albemarle Sound, “the direction and guidance from the Scientific Advisory Council is to expand the standard through all coastal waters, and so that’s something that we’re working through with the SAC as far as how to capture that in the standards,” Higgins said.

The Division of Water Resources is working with the Division of Marine Fisheries on plans to monitor seagrasses and they will be the primary collectors of this data. “We’re working with them and their staff to see what their existing protocols are and how we can incorporate this,” she said.

Deerhake followed up with the full Environmental Management Commission during its meeting Nov. 10, explaining that the Scientific Advisory Council was to meet soon to finalize their recommendation on a standard.

Water Resources staff is to then begin drafting rules to go before the water quality committee for consideration before reaching the full commission. “Our goal is to see it in the first quarter of 2023,” Deerhake said.