Editor’s note: The following report is drawn solely from Pete Benjamin’s comments as keynote speaker at the Wings Over Water Wildlife Festival and is not presented as representative of differing points of view on the controversial Red Wolf Recovery Program in northeastern North Carolina.

KILL DEVIL HILLS — Pete Benjamin has almost 10 years of hands-on experience supervising the red wolf recovery plan at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge for the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Supporter Spotlight

Benjamin, Fish and Wildlife Service Raleigh office field supervisor for ecological services, was keynote speaker Saturday for the 2022 Wings Over Water Wildlife Festival, telling attendees he was optimistic about the species’ recovery. But he also acknowledged the process had been a difficult series of twists and turns.

Red wolves at one time filled forests and fields here, Benjamin noted.

“The early naturalists noted that the wolves in the New World were a little smaller than the wolves they were familiar with from Europe,” he said, adding, “Europeans also brought with them all their prejudices and feelings about wolves. And they set about eliminating predators as quickly as they could.”

Related: Managers report positive shift in red wolf recovery efforts

Those prejudices against predators extended well into the 20th century.

Supporter Spotlight

“My agency, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, up through the 1940s had very active program of predator eradication. That was part of our job,” Benjamin said.

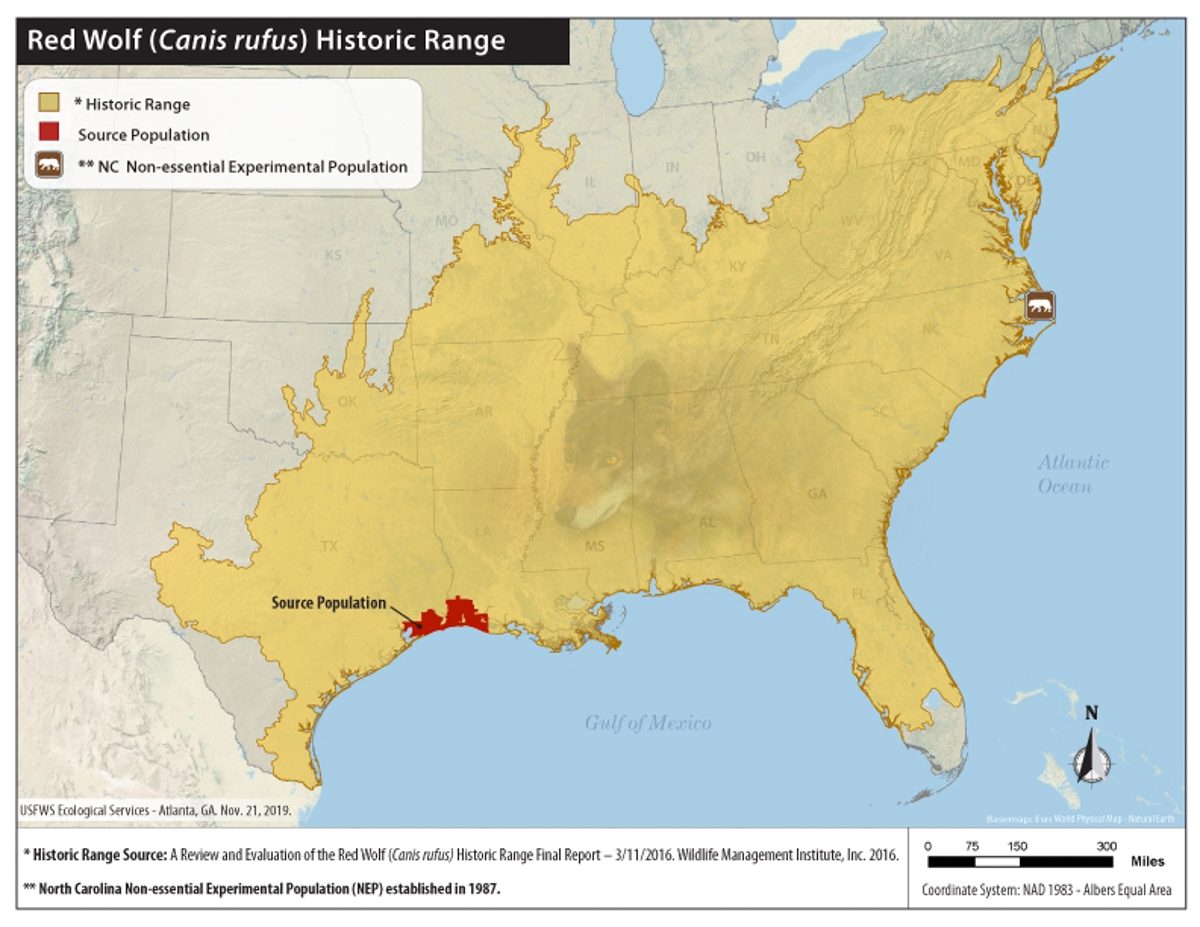

Eradication measures were effective — by the 1960s, the few remaining red wolves in the wild were cornered in a small area in southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas.

Nature, however, seeks balance, and if a predator is removed from an environment, another inevitably takes its place.

“The coyote took advantage at that point,” he said. “In the early 1900s, its range started to expand quite dramatically, and it took over that role that had been filled by the other predators.”

Canidae biology allows any animal of the species to mate with any other of the species. Typically, they prefer to mate within their own species, “But when populations fall really low, the habitat is highly altered,” Benjamin said, “they will breed with others from the genus Canidae.”

When the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966 became law, the red wolf, Canis rufus, was one of the first species recognized as being in danger of extinction. Since then, there have been numerous attempts to preserve the red wolf.

The agency’s initial response was swift, Benjamin said.

“A guy named Curtis Carley was sent by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service down to Texas. And his job was to find the last remaining red wolves and establish a buffer zone around that population to keep the coyotes and the red wolves separate,” he said.

Carley quickly realized that was not feasible. He also concluded that there were already few “true” red wolves left, and that most were coyote-red wolf hybrids.

Recognizing that the original plan for saving the species would not work, Carley crafted another solution.

“Carley came up with an idea … and it took him a few years to convince his bosses to go along with it,” Benjamin said. “They decided that the way to save the red wolf was to eliminate it from the wild. Bring the last few animals they could find into captivity.”

It was considered a bold move. “The first time ever an animal had been eliminated from the wild for its preservation,” Benjamin noted.

The Fish and Wildlife Service began trapping red wolves in the 1970s, before genetic analysis was available. Point Defiance Zoo in Tacoma, Washington, provided a captive-breeding facility, and Carley initially trapped 400 animals. He and his team developed criteria for what would be considered a red wolf, and as the captured animals bred, those criteria were applied time and again.

“They whittled it down to 14 animals,” Benjamin said. “That is the founding population of all red wolves that we know of existing today.”

The plan was never to keep the entire red wolf population in captivity. The goal was to reintroduce them to the wild. But that too was an unknown.

“Could wolves raised in zoos learn how to be wolves again in the wild? Could they find their own food? Could they defend and their own territory?” Benjamin said.

In the 1980s, agency biologists believed they had found the ideal release site: Bulls Island at the southern end of the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge on the South Carolina coast. Somewhat isolated from populated areas by extensive marsh, it seemed a good location for the wolves to succeed in the wild, but results were mixed.

The wolves did successfully hunt and establish territory. The biologists found they could successfully track the wolves, including when they left the island and ventured into nearby towns.

A larger recovery area was needed.

Then, in 1986, the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge was established, and it seemed to check all the boxes for red wolf recovery, especially its size — 140,000 acres. Combined with the adjacent Navy bombing range, the wolves would have almost 200,000 acres total. And, perhaps most importantly, coyotes had not yet reached the region. After outreach to residents living near the refuge, breeding pairs were released into Alligator River.

Again, the learning curve for the field biologists was steep. The wolves covered far more territory than originally thought, with some of them roaming to Manns Harbor.

“And they eat a lot of deer. They really like deer,” Benjamin said.

Elsewhere, that may not have been important, but area hunters had been assured the wolves’ diet consisted almost entirely of smaller mammals.

Nonetheless, the population thrived, so much so that another first for reintroducing a species into the wild was tried.

“We developed the technique of cross-fostering,” he said. “They learned that if there was a litter of puppies born in the zoo at very nearly the same time as a litter in the wild, they can take puppies from that captive litter and just insert them into the wild. Since wolves can’t count, they just raise those foster puppies as their own. Puppies will grow up with all the experience and knowledge that they need to succeed.”

That appeared to work until the coyotes showed up in eastern North Carolina in the 1990s. Although research has subsequently demonstrated that red wolves will only breed with coyotes when there is no other option, in the 1990s that information was not yet available.

“We really didn’t understand at the time the dynamics that leads to interbreeding between red wolves and coyotes,” Benjamin said.

To prevent interbreeding, wildlife management scientists came up with another idea. The 1999 red wolf adaptive management plan was the first of its kind for the agency and the keystone was that, instead of just trying to remove the coyotes, they instead sterilized them.

Coyotes, like all canids, are territorial, and a breeding pair of coyotes will continue to protect its territory even if they can no longer reproduce.

But the plan did not address the larger issue of the exploding coyote population. As coyotes became more prevalent, hunting restrictions were relaxed. Hunters, unfamiliar with red wolves, too often mistook them for coyotes.

“Up until that time, vehicle mortality had really been the leading cause of death, natural causes a close second, but in about 2004, 2005, or so, gunshot took over as leading cause of death,” Benjamin said.

As he explained, for red wolves, highly dependent on their well-developed social structure, the death of a breeding pair or even one of the breeding pair, could halt reproduction for the entire season. The population plateaued at 120, Benjamin noted.

“And then it got a bit worse,” he said.

Concerns about the coyote population intersected with law and politics and the result was a stunning drop in cooperative efforts to protect the red wolf.

In 2012, the North Carolina Wildlife Commission permitted coyotes to be taken in daytime or night and allowed hunters to use spotlights.

“That prompted a number of environmental groups to challenge the state in federal court, saying that was going to inevitably lead to more take of red wolves in violation Endangered Species Act.

For a while, the judge banned hunting of coyotes in the five-county Albemarle Peninsula, Benjamin said.

It was a legal victory, but the cost to the red wolf management program was nearly catastrophic. Landowners adjacent to the refuge, who had been cooperative or indifferent to the management plan, suddenly no longer permitted access to their property.

“A lot of landowners just said, ‘Fish and Wildlife Service, you’re not allowed on my land,’” Benjamin recalled.

Effective red wolf management requires a hands-on approach. Dens need to be located, collars and tags are important for tracking the species and the health of litters is important to note. Without that information, management became difficult, almost impossible, and the result was a collapse of the wild red wolf population.

“By the 2018 we were down to where there were no remaining breeding pairs in the wild” Benjamin said.

Yet even as the Alligator River program was teetering on the brink of failure, there was reason for optimism for the species overall.

“At that same time, we were working hard with the (wolf) population under human care in zoos in 49 facilities around the country to grow the size of capital population because with only 14 animals that was the starting population, retaining the genetic diversity of species is very difficult to gain,” he said.

Then a second site, St. Vincent National Wildlife Refuge in Florida, produced a litter in the wild.

“That project is going on very well,” Benjamin said.

Alligator River, though, is still the primary test site for wild red wolf recovery. Here, there has been some recovery from the 2018 low of eight wolves and no breeding pair. For the first time since 2014, the agency is again releasing captive-bred wolves into the wild.

Many of the problems that plagued the program in its earliest days returned.

“There were no wild mating pairs so you could not do pup fosters. So, we’re back to where we were in the beginning of releasing adult zoo raised wolves,” Benjamin said.

Some wolves have wandered into towns and had to be removed. Others were hit by cars. A few were shot. But earlier this year, a litter of six wild wolf pups was confirmed, the first wild litter since 2018.

And the agency is trying to do better at working with locals.

“We’re spending a lot more time trying to work with people, landowners, stakeholders. We spend a lot of time talking to folks, understand their concerns, do everything we can to address those concerns,” Benjamin said.

Recognizing that attitudes about coyotes are unlikely to change and hunting continues, released red wolves are now fitted with orange collars.