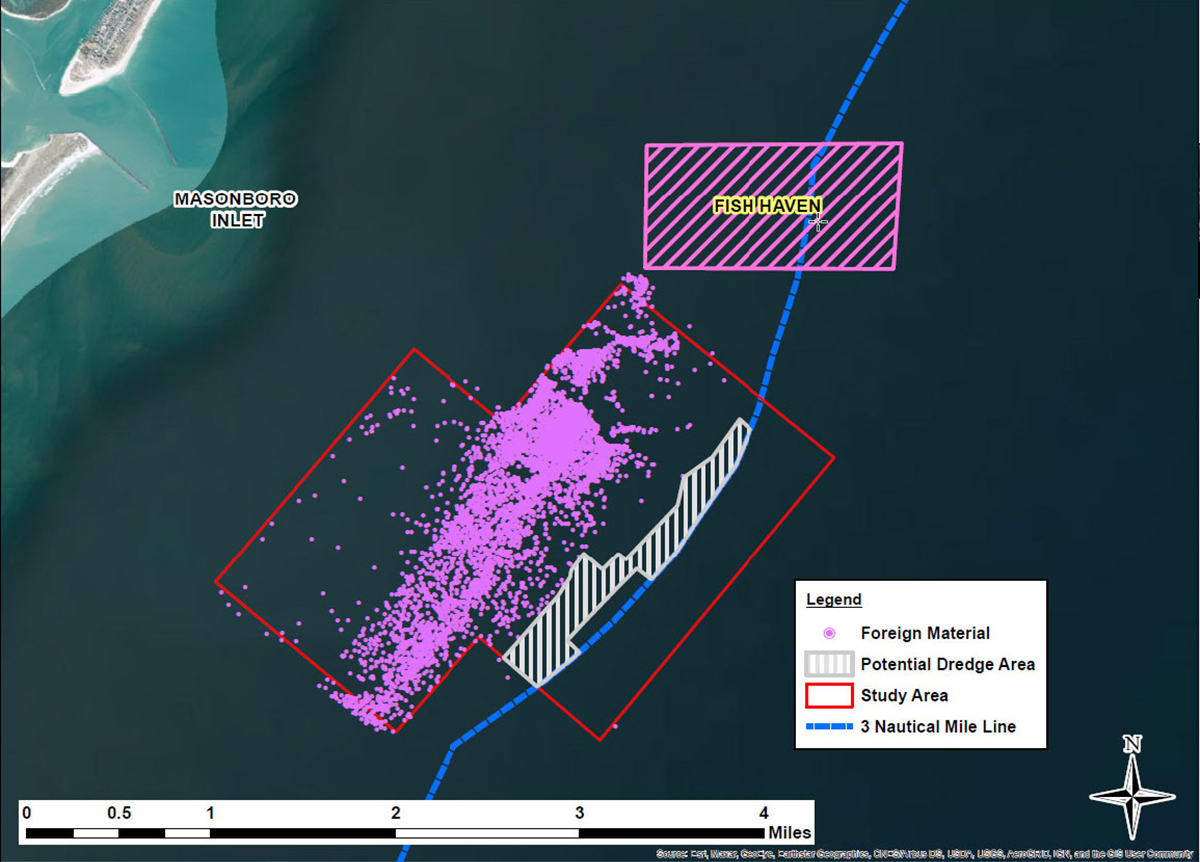

Some 300,000 tires that have broken free from a decades-old artificial reef are scattered along an area of seafloor tapped as the new sand borrow source for Wrightsville Beach.

The tire debris field is not halting plans to pump material from the offshore site next spring onto the town’s ocean shoreline, which is already behind schedule in receiving a sand injection.

Supporter Spotlight

“The good news is that now that we know they’re there we can plan and mitigate for them,” said Dave Connolly, Army Corps of Engineers public affairs chief for the Wilmington district. “We’re going to be able to work and plan with the contractor to have more robust plans, which are being developed now for screening, and everything we can to mitigate the fact that we know there’s some potential to have tires out there.”

Whether its shipwrecks or other foreign debris, rocks or fine soil that’s not suitable to be pumped onto a beach, there’s always a risk of running across material along the seabed that dredges need to avoid.

Coming across the occasional scrap tire on the ocean floor is not uncommon, Connolly said, but it is “unusual that there are so many.”

Scrap tire reefs

The tires are suspected to have drifted from Artificial Reef 370, also referred to as Meares Harriss Reef, one of 43 man-made ocean reefs managed by the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries.

Over time, coastal storms have caused the tires to break free from where they were once tethered together, resting on the ocean floor among sunken tugboats, barges and concrete pipes used to create the reef off Wrightsville Beach.

Supporter Spotlight

It is unclear just how many scrap tires were placed in the reef.

“The problem is we don’t know the exact number of tires that were deployed,” said Patricia Smith, public information officer for the Division of Marine Fisheries.

Documents that state fisheries officials have on file vary: An estimated 56,500 tires were placed in 1973 and another 318,708 tires were added to the reef between 1973 and 1984. There’s documentation that 167,500 tires were placed at 370 and Artificial Reef 378, which is off the coast of Carolina Beach.

“We really cannot verify any of those numbers,” Smith said. “We can say we believe it exceeds 600,000 statewide.”

State fisheries began taking over artificial reefs off the state’s coast in the early 1970s.

Prior to that, offshore artificial reefs were built by different fishing clubs to produce fish habitat and bolster attractive fishing grounds.

The practice of using scrap vehicle tires to build up ocean artificial reefs began back in the late 1950s or early 1960s, according to the “2020 Guidelines for Marine Artificial Reef Materials,” a publication of the Atlantic and Gulf State Marine Fisheries Commissions.

Using old tires to build artificial reefs was an acceptable low-cost alternative disposal option for millions of stockpiled tires through to the early 1980s. North Carolina stopped using scrap tires to build ocean artificial reefs around that time.

Today, most states have banned the use of scrap tires for artificial reefs.

The emergence of new markets for scrap tires in the early 1990s have provided alternatives for reducing, reusing, recycling old tires.

But millions of tires remain in artificial reefs along the nation’s coasts.

In Mississippi, scrap tires were fastened together with cables and placed in the hulls of ships being deployed as artificial reefs.

An estimated 1 million to 2 million tires were deployed as an artificial reef near Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Off the coast of Virginia Beach, Tower Reef, Virginia’s primary tire reef, was built in the 1970s using 400,000 scrap tires.

From ocean floor to shore

In 1994, tires from that reef began washing up on Corolla’s ocean shoreline after storm events.

About 100,000 tires have been removed from North Carolina beaches since 1989 at a cost of more than $1 million, according to the commission’s 2020 report.

The state does not plan to retrieve tires from the ocean because it’s not cost-effective, Smith said.

In 2001, volunteer divers retrieved 1,600 tires from the reef off the Coast of Fort Lauderdale. The tires were removed and recycled at a cost of $20 per tire.

At that rate, removing all tires from the reef “may run into tens of millions of dollars,” according to the 2020 Guidelines for Marine Artificial Reef Materials.

“We do have a plan in place to get these tires off the beach when they wash up,” Smith said. “Sometimes we go and collect them. Sometimes, if it’s just a few, the town will go and pick it up.”

The state has occasionally used prison labor to pick up tires that have washed ashore on Bogue Banks in Carteret County.

“Those are usually for when there are really large amounts that come ashore,” Smith said.

New Hanover County Shoreline Protection Coordinator Layton Bedsole said he can’t recall officials in the county’s beach towns “being unusually upset about tires on the beach.”

“I know they’re out there,” he said.

New site, new headaches?

The cutter dredge used to pump sand onto the ocean shorelines of Carolina Beach and Kure Beach earlier this year sucked up a handful of tires during operation.

“They had to stop production, get it unclogged, and get it back to work,” Bedsole said. “It slowed down production.”

The Meares Harriss Reef is a little more than 2.5 miles from Masonboro Inlet, an area of which was Wrightsville Beach’s sand borrow source for decades before a legal interpretation forced the Corps to find an offshore site.

Wrightsville Beach had for years been getting beach quality sand from an area of the inlet that lies within Coastal Barrier Resources System Unit L09.

This is an area designated as part of the Coastal Barrier Resources Act, or CBRA, a law Congress passed in 1982 to discourage building on relatively undeveloped, storm-prone barrier islands by cutting off federal funding and financial assistance, including federal flood insurance.

CBRA, pronounced “cobra,” was also established to minimize damage to fish, wildlife and other resources associated with coastal barrier islands.

The interpretation of the law as it pertains to whether sand that is within a CBRA zone may be dredged and pumped onto a beach outside of a CBRA zone has been kicked back-and-forth between federal regulatory agencies for years.

Last year, the Biden administration overturned a 2019 decision by then-Interior Secretary David Bernhardt, who determined that federal funds could be used to pay for dredging sand within CBRA units and for placing that sand on beaches outside of those units for shoreline-stabilization projects.

The new interpretation of the law ultimately pushed Wrightsville Beach’s project off track to get sand this year. Meanwhile Costal Storm Risk Management, or CSRM, projects moved ahead this year at Carolina Beach and Kure Beach because the Corps already had offshore sand borrow sites for those towns.

New Hanover County’s beach towns are some of the Corp’s earliest CSRM projects.

When asked what his biggest concern is about the pending project in Wrightsville Beach, Bedsole said, “That we’re not using the inlet borrow site that we’ve used for 50 years and we’re taking a site that’s documented to have a tire debris field associated with it. We should be using the inlet borrow site.”

Once the Corps develops a plan for the project the agency will publish a public notice to allow for public comment, Connolly said.

It is unclear whether the project’s cost will increase.

“That’s all being determined with the project delivery team,” Connolly said. “Obviously it’s going to be factored in for sure.”

He said the goal is start pumping sand on the beach around March of next year.