“Local” qualifies as one of the most overused words of the early 2000s. So commonplace then on restaurant menus, in food markets and in food media, “local” became a dubious descriptor even co-opted by nonfood companies (local landscaping anyone?). All the hyperbole culminated in “Farm to Fable,” an investigative series that earned journalist Laura Reiley a Pulitzer Prize nomination for exposing misleading claims around local food.

That’s too bad because eating local still matters at a deeper level than the cliché “local” leads us to believe.

Supporter Spotlight

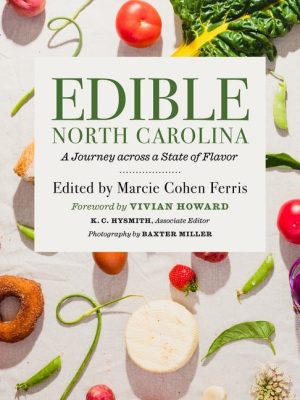

“Eating is never as simple as we might imagine,” writes author and editor Marcie Cohen Ferris as she introduces 20 leading activists, chefs, farmers, entrepreneurs, scholars and others in the food realm who penned essays for her new book “Edible North Carolina: A Journey Across a State of Flavor.”

The writers Ferris unites demonstrate the complexity, reach and significant impacts of local food in North Carolina. They extend stereotypical farm-to-table’s narrow boundaries out to what Ferris calls “the story of the contemporary food landscape.”

“Edible North Carolina” presents a panorama that encompasses the state’s food history, heritage and Indigenous and regional tastes like the Lumbee Tribe’s collard sandwiches in Robeson County and Down East commercial fishers’ favorite wild-caught scallop fritters. New voices broaden local flavors and concentrate food activism on today’s issues of access, equality, sustainability, reconnection, diversity and inclusivity.

“When I arrived in Cary and became the first Latina food columnist for the local newspaper, the resistance to my voice was swift,” Sandra A. Gutierrez writes in her “Edible North Carolina” essay. She recalls a subscriber in the mid-1980s upset that “her beloved paper had chosen a ‘Mexican’ as the writer for its food section.”

“Had I capitulated to this racism, I would not have witnessed the birth of a new culinary movement in the region. I embraced the culinary traditions of my southern white and Black readers but at the same time found my passion to introduce them to a global world of flavor.”

Supporter Spotlight

Baby steps like pulled pork tacos and chipotle in barbecue sauce that Gutierrez and others helped guide over the years led to a 2022 James Beard best chef southeast award nomination for Indian-born Cheetie Kumar of Raleigh’s acclaimed Garland. The restaurant’s Indian and Asian flavors and techniques are “driven by in-season ingredients from our home in Raleigh,” Kumar writes in “Edible North Carolina.”

Population migration has shaped North Carolina’s food landscape since the beginning. Ferris, a southern-foodways-focused professor emerita of American studies at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, traces the state’s “edible history” from Indigenous people to African, English, Scottish, Irish, European and more influences. The mix is responsible for the state’s distinctive and nationally celebrated flavor — North Carolina took three James Beard Awards in 2022. That food scene nurtures understanding and acceptance of immigrant populations.

That’s good news, but behind the scenes, local food culture is ailing.

Lack of food access, poor pay for food industry workers, big agriculture consuming small farms and the fragility of centralized food supply chains are just some symptoms. The COVID pandemic, climate change, political divisions and the immigration crisis have magnified problems that are affecting the “economic livelihoods of thousands of North Carolinians in ways unimaginable in the past,” Ferris writes.

“Now more than ever we viscerally understand what it means to lose local farms, entrepreneurs, food markets, food banks, school cafeterias, beloved neighborhood restaurants and landmark food venues.”

“Edible North Carolina” contributors take readers through a range of unsettling emotions as they describe what is being lost but then lift them up with exciting changes driven by the many challenges.

Carla Norwood and Gabe Cummings offer a heartbreaking account of how Warren County’s once-thriving farm economy has declined over the past 50 years, including the farm that has been in Norwood’s family for generations. Residents who long had access to fresh, healthy, local food face decreasing numbers of supermarkets. Just two remain in the entire 444-square-mile county. Tiny downtown Warrenton alone hosted four bustling food markets 100 years ago.

As agriculture has waned, so have job opportunities. The poverty rate is high; a quarter of the population is food insecure.

“All the cues from the modern world seem to say: leave this place behind; go to a city with high-paying jobs where you can shop at upscale supermarkets and eat in trendsetting restaurants,” Norwood and Cummings write.

“Dislocation” of local food economies, as Norwood and Cummings term it, has impacted commercial fishers as much as farmers. In 2000, Carteret County watermen faced intense competition from cheaper, inferior and unsafe imported seafood, cultural preservationist Karen Willis Amspacher, executive director of the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum and Heritage Center on Harkers Island, writes in her piece about North Carolina’s local seafood movement. Fish houses faded as pricey waterfront development overtook communities and blocked entry to public waters.

Instead of giving up, Norwood, Cummings and Carteret County families did exactly what Ferris said she hopes “Edible North Carolina” inspires readers to do: support and help rebuild local food systems that will assure food sovereignty for everyone.

“I really hope that people think about two things maybe: joy and justice,” Ferris says.

“I want people to understand their power as eaters in the state of North Carolina, as people who buy and consume foods and impact the health of their community. I think when you read this book you can start feeling what are the small ways you can help rebuild your little landscape.”

Norwood and Cummings in 2010 founded a nonprofit that connects diverse farmers and food entrepreneurs with new markets. The organization also repurposes abandoned spaces for local food processing.

Commercial fishing families organized Carteret Catch to brand local seafood, show consumers why it was better, and prove to restaurant professionals that diners were willing to pay more for it. Seafood sales increased, and more Catch groups formed along the coast.

Without that local catch and traditional seafood preparations he grew up eating in New Bern’s African American community, chef Ricky Moore would not have won a 2022 best chef southeast James Beard award for his work at Saltbox Seafood Joint in Durham. The restaurant’s devotion to local foodways helped put North Carolina on the national culinary map.

“The backbone of my business – North Carolina fish and seafood – is sourced from local fishermen and women,” Moore writes in “Edible North Carolina.”

“As a son of this place, it is my mission to uplift the fisherfolk who tend its waters and share its seafood bounty.”

“Edible North Carolina” grew from Ferris’ classroom teachings on southern and North Carolina food culture. As students listened to guest lecturers like Amspacher and collected oral histories, the need for those voices to be collected in a serious tome emerged. Still, every “Edible North Carolina” essay ends on a light note, a recipe that reflects the writer or subject’s food journey.

Norwood and Cummings share a Warren County resident’s classic sweet potato pie. Anthropologist Courtney Lewis, concerned with the loss of Indigenous foodways, offers tuya gadu, a Cherokee bean bread. First-generation Southerner chef Oscar Diaz contributes BrunsMex Stew with black beans, cilantro and fresh tomato salsa.

Recipes were important to include, Ferris says, because they “speak to a moment. They speak to history …To many generations of family.” A recipe “communicates to us in another language,” she says.

That language is one that everyone understands because everyone must eat. Cooking leads to meals, and meals can stir conversation about what local food really means and the many lives it touches. Over dinner, we might consider numerous ways to help — shopping at the neighborhood seafood market, volunteering to pull weeds at an urban farm, checking supermarket produce sections for local vegetables, lobbying lawmakers, starting a movement.

“Edible North Carolina” makes us realize that we must never let “local food” be relegated to one more meaningless marketing campaign.