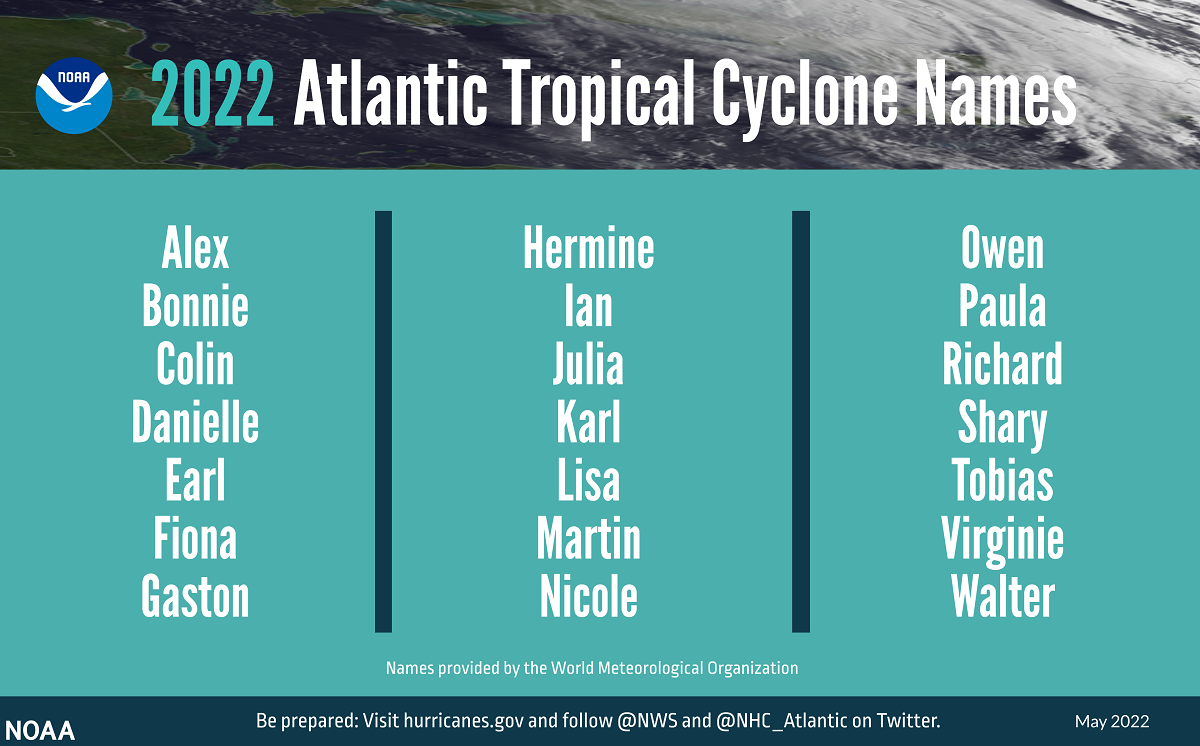

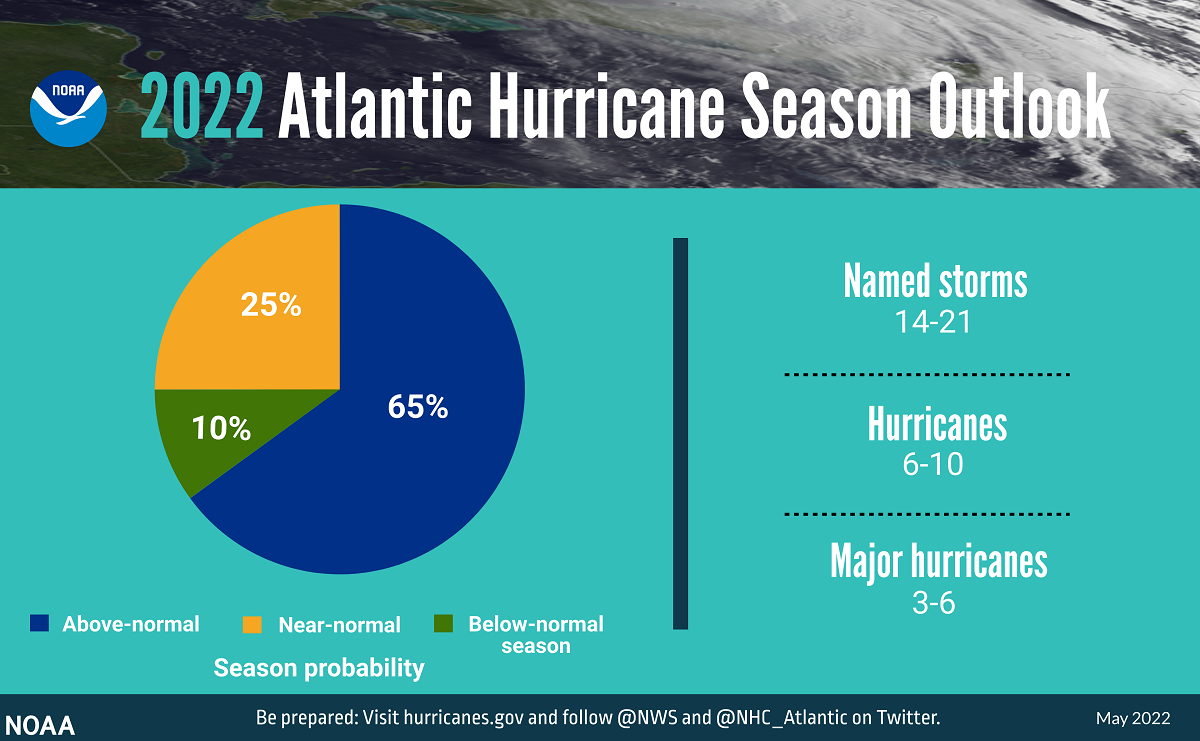

The 2022 Atlantic hurricane season, which begins next week, is predicted to have above-average activity, with a likely range of 14 to 21 named storms.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Administrator Rick Spinrad announced the initial outlook Tuesday during a news conference at New York City Emergency Management Department in Brooklyn, New York. Forecasters at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, a division of the National Weather Service, made the prediction for the season, June 1 to Nov. 30.

Supporter Spotlight

Spinrad said the 2022 prediction will make the seventh consecutive year of an above-normal season. “Specifically, there’s a 65% chance of an above-normal season, a 25% chance of a near-normal season, a 10% chance of below-normal season.”

Averages for the Atlantic hurricane season are 14 named storms and seven hurricanes. Of those, the average for major hurricanes at a Category 3, 4 or 5, is three. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center uses 1991 to 2020 as the 30-year period of record to determine averages.

For the range of storms expected, Spinrad explained that forecasters call for a 70% probability of 14 to 21 named storms, with top winds of at least 39 miles per hour. Of these, six to 10 will become hurricanes with top winds of at least 74 miles per hour, and of those, three to six major hurricanes will be categories 3, 4 or 5 with top winds of at least 111 miles per hour.

NOAA’s outlook is for overall seasonal activity and is not a landfall forecast. The Climate Prediction Center will give an update in early August before peak season, officials said.

NOAA officials attribute the increase in activity to many factors, such as the ongoing La Niña. La Niña is the cool phase of the Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, cycle. ENSO is a a three-phase recurring climate pattern that has a strong influence on weather across the United States. The other two phases are neutral and El Niño, the warm phase that suppresses hurricane activity in the Atlantic. La Niña enhances it.

Supporter Spotlight

Other factors officials point to are warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea, weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds, and an enhanced west African monsoon, which supports stronger African Easterly Waves that seed many of the strongest and longest lived hurricanes during most seasons.

“The way in which climate change impacts the strength and frequency of tropical cyclones is a continuous area of study for NOAA scientists,” according to NOAA.

Rick Luettich, director of the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences based in Morehead City and a coastal physical oceanographer, told Coastal Review Tuesday that he thinks this forecast by NOAA is not a surprise at all. “And I think we have to expect that it’s likely to hold true.”

While the range of 14 to 21 storms is broad, Luettich thinks there will be at least the 14 storms “and whether or not we stop at 21 remains to be seen. But it looks like we’ll get through most of the alphabet again this year.”

He noted that NOAA’s predictions are not substantially different from those announced a few months ago by Colorado State University researchers, who predicted 19 named storms this year. Of those, nine are predicted to become hurricanes with four to reach major hurricane strength at sustained winds of 111 miles per hour or greater. North Carolina State University researchers also predicted in April a similar amount of 17 to 21 named storms for this year.

Luettich explained that the main thing that keeps storms, which pull heat from the ocean, from fully forming is wind shear, or the variation in wind from the surface up into the atmosphere.

“If there’s a strong difference between the winds high aloft and the winds closer to the surface then that difference tends to stretch and pull and tear apart the storms,” he said. If the wind shear is weak then there’s not much to keep the storm from forming.

“Wind shear tends to be much stronger in years when we have an El Niño,” Luettich said, but this year looks to be a moderate La Niña new year.

The ENSO cycle most directly impacts whether or not there are a large number of storms, small number or somewhere in between. “The combination of a warm ocean and limited or little wind shear drives the large numbers of storms in the predictions.”

The La Niña/El Niño cycle is what allows storms to get fully going and manifest or is what tears them apart. “And from year to year, it changes,” he added.

He did point out that being in the third consecutive year of a La Niña cycle is unusual. Between plenty of energy in the ocean and weak wind shear, this is likely to be another year of substantial and strong storms.

As the storm predictions relate to climate change, “if you look at the long-term temperature records you can see in both the atmosphere and the ocean there is a steady increase in the Earth’s temperature,” he said.

Climate change is causing energy in the ocean to increase and more precipitation, leading to storms traveling slower and allowing more time for rainfall in an area. However, it’s a little less clear how the ENSO cycle is affected by climate change.

“There are suggestions that in a warming climate the La Niñas and El Niños may be stronger when they occur, but I’m not aware that there’s a really good consensus or understanding of whether they’re likely to be more frequent,” he said, adding it’s just not clear how climate change will affect the ENSO cycle.

On the North Carolina coast

Erik Heden, warning coordination meteorologist with the National Weather Service’s office in the Newport/Morehead City area, explained in an interview Tuesday that his office doesn’t focus on NOAA’s initial outlook during any given year because “it doesn’t tell us whether or not our area will be impacted by storms. We try to shift the focus toward preparation each and every year since we live in an area that is vulnerable.”

He urges residents and visitors that if there is a hurricane forecast that impacts their area, don’t focus on the category of the storm.

“The category is only related to wind speed. It says nothing about how much rain will fall, how long the storm will remain over us, how large the storm is,” he said. “Remember Hurricane Florence was ‘only’ a category 1 storm when it made landfall. Cyclones have multiple threats that include storm surge, flooding, rip currents, tornadoes and wind.”

Heden urges residents and visitors to follow official resources such as the weather office for your area or the National Hurricane Center. If your area is forecast to be near, not just in, the forecast cone, or cone of uncertainty, you should be preparing for the storm.

“The forecast cone only shows the most likely path for just the center of the storm. A storm is not a dot on the map and impacts occur well away from the center,” he said. For example, the center of Florence in 2018 hit near Wilmington, “but we all saw major impacts from the storm.”

Heden explained that preparation has three steps.

The first is to determine your risk, based on where you live, from all five tropical cyclone threats: storm surge, flooding, rip currents, winds and tornadoes. Second, have a hurricane plan and determine where you will evacuate if necessary. Don’t forget your pets.

Third, make a hurricane kit. The kit should contain enough food, water and medicine to last at least three days, but ideally up to a week. If cost is a concern, spread it out and buy a few items each shopping trip.

Heden said his office is hosting a series of community forums on hurricanes, the first of which will be held 5-8 p.m. June 14 at Holly Ridge Community Center, 404 Sound Road, Holly Ridge. The next forum will be held 10 a.m. to noon June 21 in Pine Knoll Shores town hall. Two will be offered in late July on the Outer Banks. Locations will be announced.

State urges residents prepare now

Keith Acree, communications officer with North Carolina Emergency Management, told Coastal Review Tuesday that the state and local governments make sure they are prepared for each hurricane season.

“North Carolina Emergency Management recently hosted the statewide hurricane exercise, where the State Emergency Response Team and its federal, state, local government and private-sector partners practiced response coordination and communications,” he said. “Helicopter, boat and land search and rescue teams recently held large scale exercises at the coast and in the mountains, in advance of hurricane season.”

Related: NCDOT prepares for this year’s hurricane season

Acree said residents of North Carolina’s coastal counties should learn if they’re in a predetermined evacuation zone by visiting KnowYourZone.nc.gov. “Remember your zone and listen for it when evacuations are ordered.”

He said residents should prepare by having an emergency kit with basic supplies included and have a plan to stay with family or friends, or at a hotel if you need to evacuate.

“A public shelter should be your last resort, not a primary evacuation option. Offer your home to family or friends as a safe place if they need to evacuate, and you don’t,” he said.

Acree also recommends having multiple ways to receive weather alerts, watches and warnings. Install a weather alert app on your cell phone, or get NOAA Weather Alert Radio for your home.

Lastly, remember that hurricanes and tropical storms can affect the entire state.

Residents in Haywood and surrounding counties in Western North Carolina are still recovering from the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred, a Gulf Coast storm that moved across the state’s mountains last year, causing catastrophic floods along the Pigeon River killing six people, he explained.

“It only takes one storm that strikes your community to make a really bad hurricane season for you,” Acree said. “Now is the time for North Carolinians to prepare for hurricane season.”