Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

To my friends at The Ridge

Supporter Spotlight

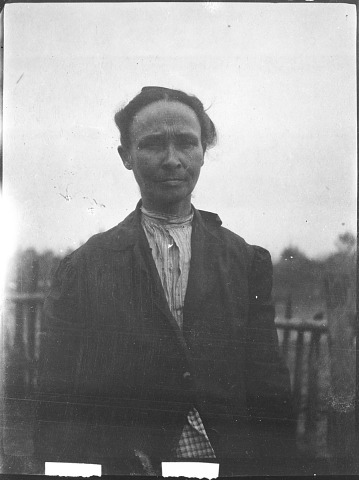

An anthropologist named Frank Speck took this photograph of an American Indian woman and child on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, in 1915. He referred to them as “Machapunga Indians” (though I will not), a tribe whose homeland had historically been the area around the Pungo River and Lake Mattamuskeet.

I found the photograph a few days after Christmas when I visited the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC.

I later learned that the original copy of the photograph is at the American Philosophical Society, the Philadelphia “learned society” that was founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1743.

Speck was a professor at Penn, just outside of Philly. He specialized in the culture and languages of the Algonquin and Iroquoian-speaking peoples of the Eastern U.S. and Canada.

At the time he visited Roanoke Island, he was probably best known for his work with Fidelia Fielding in Connecticut. She was a Mohegan Indian elder also known as Dij’ts Bud dnaca (“Flying Bird”).

Supporter Spotlight

Fidelia Fielding was the last fluent speaker of the Mohegan Pequot language. One of the many extraordinary things about her was that she kept diaries in the written version of Mohegan Pequot.

Entrusted to Speck after her death in 1908, those diaries later proved indispensable to preserving the written version of Mohegan Pequot and to making possible a revival of the language.

Fidelia Fielding’s diaries have since been repatriated to the Mohegan Tribe. They are now in the Mohegan Library and Archives on the Mohegan Tribe’s reservation in Uncasville, Connecticut.

In 1915 Speck toured Roanoke Island and the Outer Banks in search of American Indian people who might still speak the Carolina dialect of the Algonquin language.

In an article in American Anthropologist the next year, he proclaimed his findings “meager.” To me, at least, he does not seem to have understood much of what he saw or heard, but he was right about the language: Carolina Algonquin, as linguists call it, was extinct.

-2-

Though Frank Speck’s article in American Anthropologist did not impress me, I was enthralled by the copies of his photographs that I found at the National Museum of the American Indian.

There are a total of five: the photograph I have shown you already, two more of the same woman and child (taken at the same time, and in roughly the same pose) and two others.

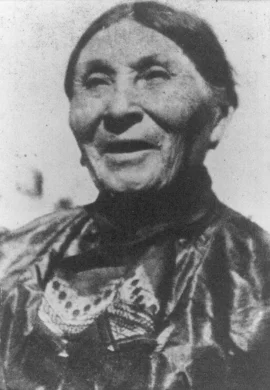

The two others are portraits of a much older Indian/African American woman who was apparently from the same family as the woman and child: a mother, grandmother or great-grandmother, perhaps.

In the American Anthropologist, Speck identified all three figures as part African American and part “Machapunga Indian.” In fact, he called his article “Remnants of the Machapunga Indians in North Carolina.”

That seems a little strange because the two women and the child identified as American Indian, but did not use the word “Machapunga” to describe their tribal background. In fact, it’s not clear that any of the coastal tribes ever referred to themselves as the “Machapunga.”

In the early 1700s, English colonists did use the word “Machapunga” to describe the Algonquin-speaking Indians that resided in the vicinity of the Pungo River and Lake Mattamuskeet.

The Pungo River and Lake Mattamuskeet are both located southwest of Roanoke Island—the river perhaps 50 miles southwest, the lake 30 miles southwest.

The English used the word “Machapunga” in the early 1700s, but earlier accounts refer to the Algonquin-speaking Indians on that part of the North Carolina coast as the “Secotan.”

Later accounts, on the other hand, often employ more local terms, such as “Pungo River Indians” or “Mattamuskeet Indians.”

The only translation of the word “Machapunga” from the Algonquin to English that I have seen indicates that it means “bad dust” or “much dirt.” If that is correct, that does not sound like what a people would call themselves.

For those reasons, I think it is possible that “Machapunga” was what geographers call an exonym—a name, often but not always pejorative, that outsiders use to describe a place or a people, but one that the people in that place do not use.

-3-

Frank Speck did not identify the younger Indian woman or the young girl in his Roanoke Island photographs by name. However, he did identify (a bit incorrectly, it turns out) the older woman in his photographs as “Mrs. M. H. Pugh.”

“Mrs. M. H. Pugh” was Annie Mariah (Simmons) Pugh, and her late husband’s name was not M. H. Pugh, but Smith Pugh. (M. H. Pugh was one of their sons.)

With a little genealogical research, I discovered that Annie Mariah Simmons (later Pugh) was born on the Pungo River, not far from the present-day towns of Belhaven and Pantego.

In his article in American Anthropologist, Speck confirms my findings. He says that she “was born and raised in the Pungo River district” and referred to herself as a “Pungo River Indian.”

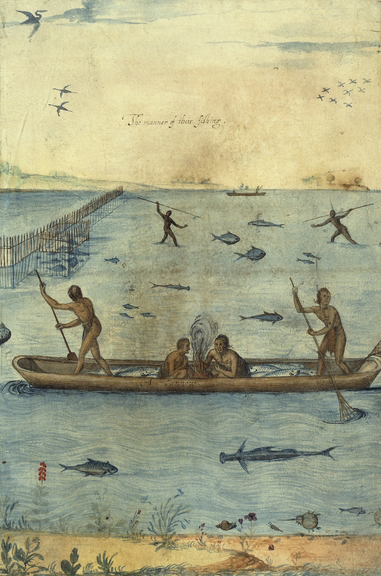

The place of her birth was an important one in the history of Native America. One of the first encounters between American Indians and the English occurred on the Pungo River in the 1500s.

In the summer 1585, an English reconnaissance party explored the region around the Pungo River. While there, they visited a village called Aguascogoc twice.

On the first visit, the English traded with the people of Aguascogoc. But on the second visit, the English burned the village to the ground and torched its croplands.

To my knowledge, Aguascogoc was the first Indian village that the English destroyed anywhere in North America.

-4-

When Frank Speck visited Annie Pugh on Roanoke Island in 1915, he estimated “her age to be about eighty years.” That seems to have been correct. According to census records, she was born in 1838 so she was 77 years old at that time.

At the age of 17, she married Smith Pugh, a Hatteras Island Indian who made his living at times by going to sea, but mainly by fishing and probably doing a little farming, too.

Like many of the old Outer Banks families, he had a multiracial background, as did Annie. (By “multiracial, I mean some combination of European, African and/or Native American ancestry.)

Both identified however as Indian (though not necessarily only Indian): she, as I mentioned, as a “Pungo River Indian,” and Smith as a member of the Hatteras Island tribe.

Smith and Annie Pugh moved closer to his home on Hatteras Island sometime after the Civil War and had a family of 13 children, though only eight seem to have survived to adulthood.

The identification of their and their children’s races in the federal censuses that were done every 10 years reflects the family’s multiracial identity and the way that America looked at race in that day.

Between the Civil War and 1900, federal censuses listed the race of the Pughs and their children at times as “mulatto,” at times as “white” and at times as “black.”

The censuses never listed any of them as “Indian,” “American Indian” or “Native American,” however.

Those were not really options at that time. Prior to 1900, the federal census counted few native people anywhere in the United States.

That exclusion had deep historical roots: as hard as it is to imagine, the United States Constitution specifically prohibited Native Americans from becoming U.S. citizens. That did not change until 1924, when the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act.

If a census taker identified an individual as part-Indian, part-white or part-Black (or part any other race) and decided to count them, they typically listed that person as being a race other than American Indian.

-5-

The Pughs were a fishing family. They lived mainly on the Outer Banks, and Smith Pugh and his and Annie’s three sons were all fishermen. It was a poor man’s existence: the children had little, if any, time for schooling and the boys often began working on the water by the time that they were 11 or 12.

The 1880 federal census, for instance, already lists their 12-year-old son Melton as a fisherman.

Fishing was a hard life, but had its advantages, too. If you were descended from the coastal Algonquins, one of those advantages may have been having a sense of connection to one’s ancestors. After all, American Indians had been fishing on those waters for thousands of years.

That same 1880 census lists Annie Pugh as “keeping house.” In a fisherman’s family of at least eight children, “keeping house” was of course no small job. Annie probably rose earlier and stayed up later than anyone else in the household and was surely a stranger to idle hands.

Annie’s husband, Smith Pugh, died sometime around 1900. Frank Speck, our anthropologist from Penn, met Annie Pugh 15 years later, the year before she died. She passed in Nags Head, on Bodie Island, in 1916.

The identities of the woman and child in the other photographs remain a mystery. Mostly likely the adult woman was Annie Pugh’s daughter, granddaughter, or great-granddaughter. The girl, I assume, was the unidentified woman’s daughter.

Whoever the mother and daughter in that photograph were, I love their poise and fearlessness and how they are looking at the stranger who is taking their photograph.

There is something about their unabashed gazes that I just find incredibly compelling. They both seem to know exactly who they are, and they both seem to be looking straight into Speck’s soul.

Maybe it is my imagination, but the mother, at least, seems a bit skeptical of what she sees there, though perhaps she was just skeptical of why he was there at all.

-6-

Annie Pugh’s ties to the Pungo River Indians reminded me of a story that I heard some time ago. That was in 2004, when I was in Wenona, a rural community a little north of the Pungo River and just west of what is now the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge.

I was in Wenona to do an oral history interview with an 88-year-old white woman named Rachel Stotesbury.

Mrs. Stotesbury had lived in Wenona since she married a local farmer in the 1930s. (You can find the story I wrote about her here.)

During my visit, Mrs. Stotesbury told me that her father-in-law remembered when a band of Indians still lived in the headwaters of the Pungo River.

According to Mrs. Stotesbury’s father-in-law, the Indian settlement was located at a place called Davis Landing, which at that time was in a remote, roadless tract of swamp forest in the headwaters of the Pungo River, perhaps 20 miles upstream of Annie Pugh’s childhood home.

In those days, the headwaters of the Pungo River still lay in the heart of what was called the Dismal Swamp (or sometimes, the “East Dismal Swamp,” to distinguish it from the Great Dismal Swamp on the other side of the Albemarle Sound).

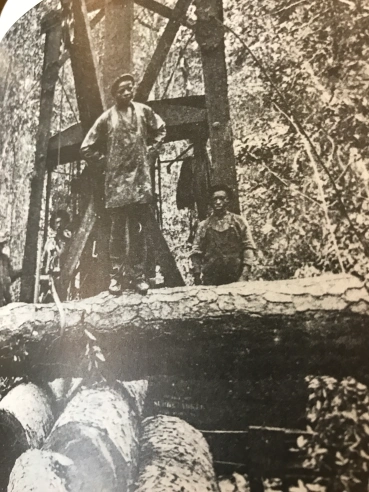

Even at the end of the 19th century, the East Dismal Swamp (as I’ll call it) still covered hundreds of square miles: it was a seemingly endless sea of ancient cypress forests, juniper stands and pocosin wilderness.

Pocosin is an Algonquin word for a distinctive type of raised peat bog that is only found in southeast Virginia and on the coastal plains of North and South Carolina.

But in the late 1800s, timber companies began moving into the East Dismal in a big way. They dug massive canals, drained the swamps and cut down every last acre of the old-growth forests.

They also built the region’s first railroads. Along the new rails, they hauled the swamp’s massive logs to lumber mills in company towns built on the edge of the swamplands. The Roper Lumber Company built the largest mills, one in the town of Roper, the other in the town of Belhaven.

After the forest was gone, the timber companies sold the land to be used for farming. And as the East Dismal vanished, so did the native peoples, at least the ones at Davis Landing.

-7-

Frank Speck’s photographs at the National Museum of the American Indian also reminded me of a place dear to my heart.

Ten or 15 miles east of the Pungo River, my family and I often visit a friend who is descended from the Algonquin Indians that have lived so long on that part of the North Carolina coast. She lives in a community on the edge of Lake Mattamuskeet where many of her neighbors are also the descendants of those tribes.

My family and I like to go there particularly this time of year, when the great flocks of snow geese and tundra swans have come down from the far north and made the lake their winter home.

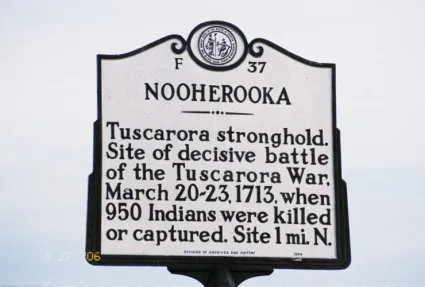

The community’s roots go back to the Tuscarora War of 1711-1715, when the Algonquin tribes that lived in the vicinity of the Pungo River and Lake Mattamuskeet joined forces with the Tuscarora and several other Algonquin tribes to wage war against the English colonists.

When they fell in defeat, some of the survivors retreated into the East Dismal Swamp and into the swamplands along the Alligator River.

They refused to surrender, and one colonial leader complained that they were “expert watermen” and could not easily be tracked.

In 1727 English leaders carved out a reservation for them on lands running from Lake Mattamuskeet and the present-day town of Engelhard south to Wysocking Bay.

Other Tuscarora War refugees apparently joined them on the reservation lands at Lake Mattamuskeet —a few Coree at first, and later a small number of Indians from Hatteras Island and Roanoke Island.

The Mattamuskeet Indian Reservation did not last long, however. The last of the reservation’s lands was sold to non-natives in 1761.

Nevertheless, many of the reservation’s families clung to Lake Mattamuskeet and the waters of the Pamlico Sound. Many remain there to this day. And as I come to appreciate more every time I visit, they are part of a strong, loving and giving community with roots in that land that go back thousands of years.