Sure it’s there, but are the algae blooms made up of teeny-tiny organisms clumped together on the water’s surface harmful?

Can it make people sick, kill oyster larvae or fish?

Supporter Spotlight

The University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Algal Resources Collection, or ARC, which recently received a nearly $600,000 grant, aids researchers and scientists throughout the world in determining those answers.

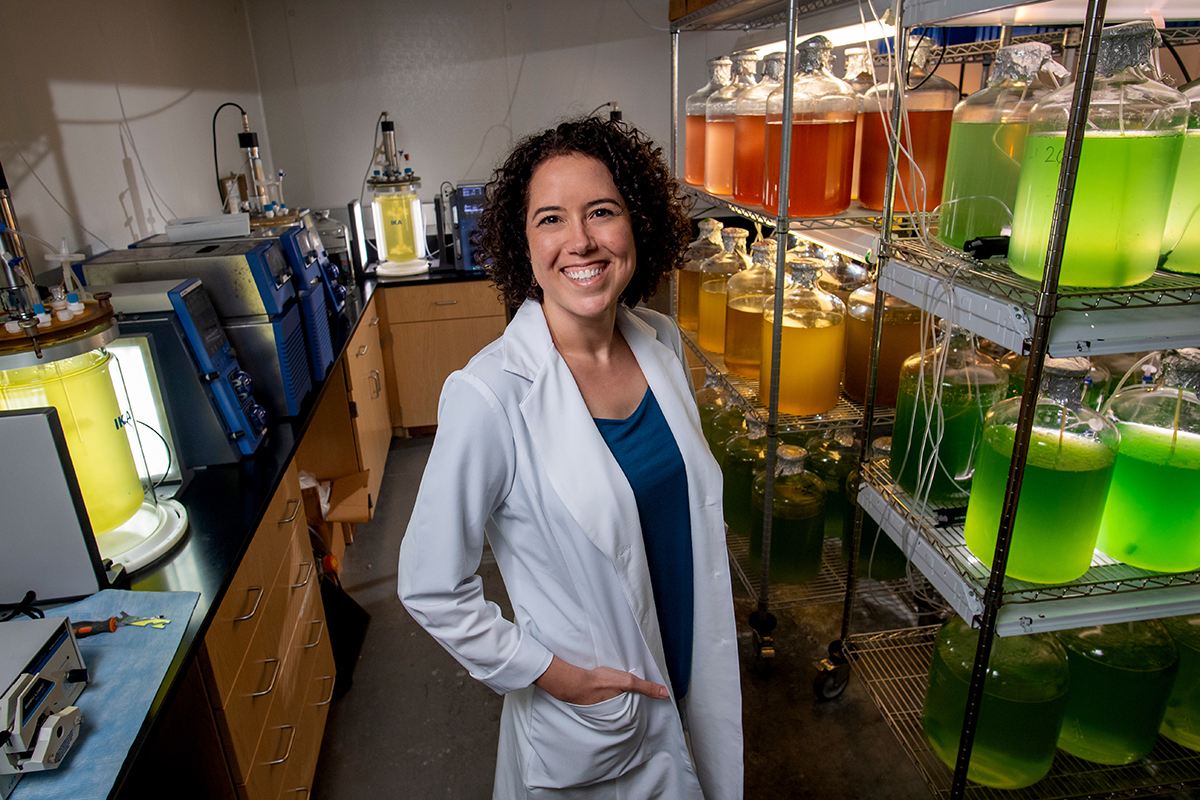

What differentiates UNCW’s collection from other microalgae culture collections in the United States is its ever-expanding catalog of harmful microalgae cultures, explained research professor and ARC Director Catharina Alves-de Souza.

Alves-de Souza is responsible for organizing, updating and making the collection accessible to researchers around the globe.

Her work is a key piece of a larger puzzle in the study of microalgae species that cause harmful algal blooms.

“These cultures, the nice part about them is that we can use them to characterize the species,” Alves-de Souza said. “We can determine the identity of the species by using the DNA. We can determine whether they’re toxic or not and we can also, with the help of chemists, determine which toxins they produce. We can get a lot of information that does help to understand what the other scientists are getting from the field samples.”

Supporter Spotlight

The three-year, $581,765 grant from the National Science Foundation she was recently awarded will cover the cost of a new machine that will expedite the identification process of microalgae species.

Using an instrument based on imaging flow cytometry, the machine is basically an automated microscope equipped with a high-speed camera that can be trained with artificial intelligence to identify various microalgae species — think technology similar to that used in facial recognition.

“These machines allow us to look for a lot of samples from blooms in a short period of time to determine which species are present in the samples,” Alves-de Souza said. “This also allows us to check for contaminants in the culture. That’s going to be very important because then we are going to make this information available and all the researchers, not only in the United States, but also institutions in other countries, will be able to use this same information, and use the same protocols.”

Money from the grant will also be used to store some microalgae cultures through cryopreservation, a freezing process that extends the shelf-life of an organism by years. This method of storage doesn’t work on all microalgae species, but it will shave some time that has to be dedicated each month to transfer cultures to new flasks to keep them growing and readily available for purchase.

This is the second grant, the first was awarded in 2018, Alves-de Souza has received since she was hired by the university in December 2016.

The microalgae species collection her predecessor built over the course of more than 20 years needed to be organized, expanded and publicized as a public resource on a website in serious need of an update. That first grant covered those goals.

At the same time, Alves-de Souza began to contribute a much-needed addition to the collection.

“In the beginning the collection had only marine species,” she said. “The freshwater bacteria is actually one of the main problems here in North Carolina.”

Alves-de Souza is using the cultures to gain an understanding of the ecology of these toxic microalgae and how environmental conditions determine the formation of harmful algae blooms. That information, she said, will help researchers like her learn how to mitigate these toxins.

Take microcystin, for example. This algal toxin is listed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as a potent liver toxin and possible human carcinogen and it has been found in different freshwater systems in the state. In her research, Alves-de Souza found microalgae producing toxins that were not previously found in North Carolina, including microalgae that produce paralytic toxins.

Alves-de Souza stressed that she hasn’t found the species in high cell concentrations in the environment, “but it’s important that we know that they are there and that we understand their ecology so we can predict if the environmental conditions change, if you are going to have blooms of these particular species in the future. It’s not a problem now, but we know that the species is there so it’s important to know what species we have there so that we can be prepared.”

She is collaborating with Nathan Hall, a research assistant professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences, to investigate the effects of harmful algae on oyster larvae.

Raphidophytes is a class of algae that has been shown “to do nasty things” to Japanese pearl oysters, but no one has studied whether this species impacts eastern oyster larvae, Hall said.

“Catharina has one of the best collections of raphidophytes in the world,” he said. “She gave me lots of different strains of cultures that I can test against and see if they do anything to kill eastern oyster larvae. That project’s still ongoing.”

Hall refers to himself as a phytoplankton ecologist, one trying to unlock the mysteries of these microscopic organisms that form the base of the food chain in the ocean.

“There’s hundreds of species of phytoplankton out there in the water,” he said. “What makes certain ones do well in certain areas at certain times of the year is a question I think a lot of phytoplankton ecologists have and it’s an important question sometimes, especially when one of those species does well as toxic, for example. To do that, first you have to know what species are there. And, in some cases, you really have to be able to culture it to tell what’s even there. That’s one of the things Catharina’s collection is doing.”

From red tide in Florida to paralytic shellfish poisoning blooms in waters north, “bad” algae are around us here in North Carolina.

“Even though we think it’s the same species just because it looks like the species, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s producing the same toxin or any toxin at all,” Hall said. “Having the cultures of that species already in a library somewhere, if all of a sudden we started having a problem with one of these algae that are harmful somewhere else, we could go then to that library collection and see whether if ours produces the same toxin. It’s just a matter of keeping an eye (on it) and so having those cultures already there could be really useful.”