Editor’s note: Coastal Review is sharing this work by historian David Cecelski in recognition of Black History Month.

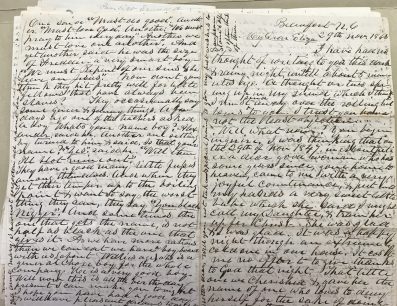

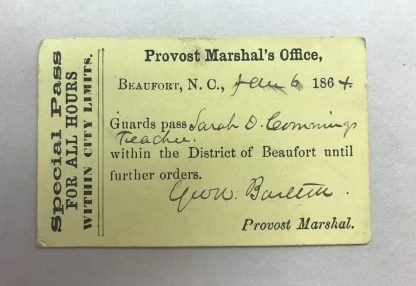

When I was at Oberlin College last summer, I stopped by the library so that I could look at the letters that the Rev. Elam J. Comings and his daughter Sarah wrote when they were in Beaufort during the Civil War.

Supporter Spotlight

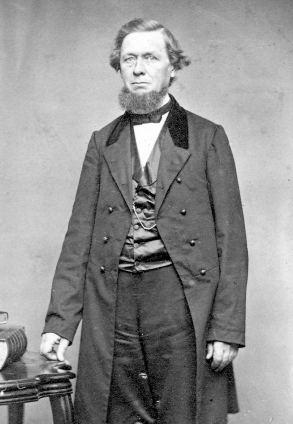

I was interested in Elam and Sarah Comings’ letters because they were written in 1863-64, when they were teachers at the Whipple School, an American Missionary Association, or AMA, school in Beaufort. Most of their students were African Americans who were slave laborers until Union forces captured the town and liberated them in 1862.

When Elam and Sarah arrived in Beaufort, the vast majority of North Carolina remained in Confederate hands. Slavery was of course still the law of the land in that section of the state.

Things were different in Beaufort, New Bern and a few other coastal towns, however. Held by the Union Army, they made up a narrow sliver of the North Carolina coast where African Americans could come out of the shadow of slavery.

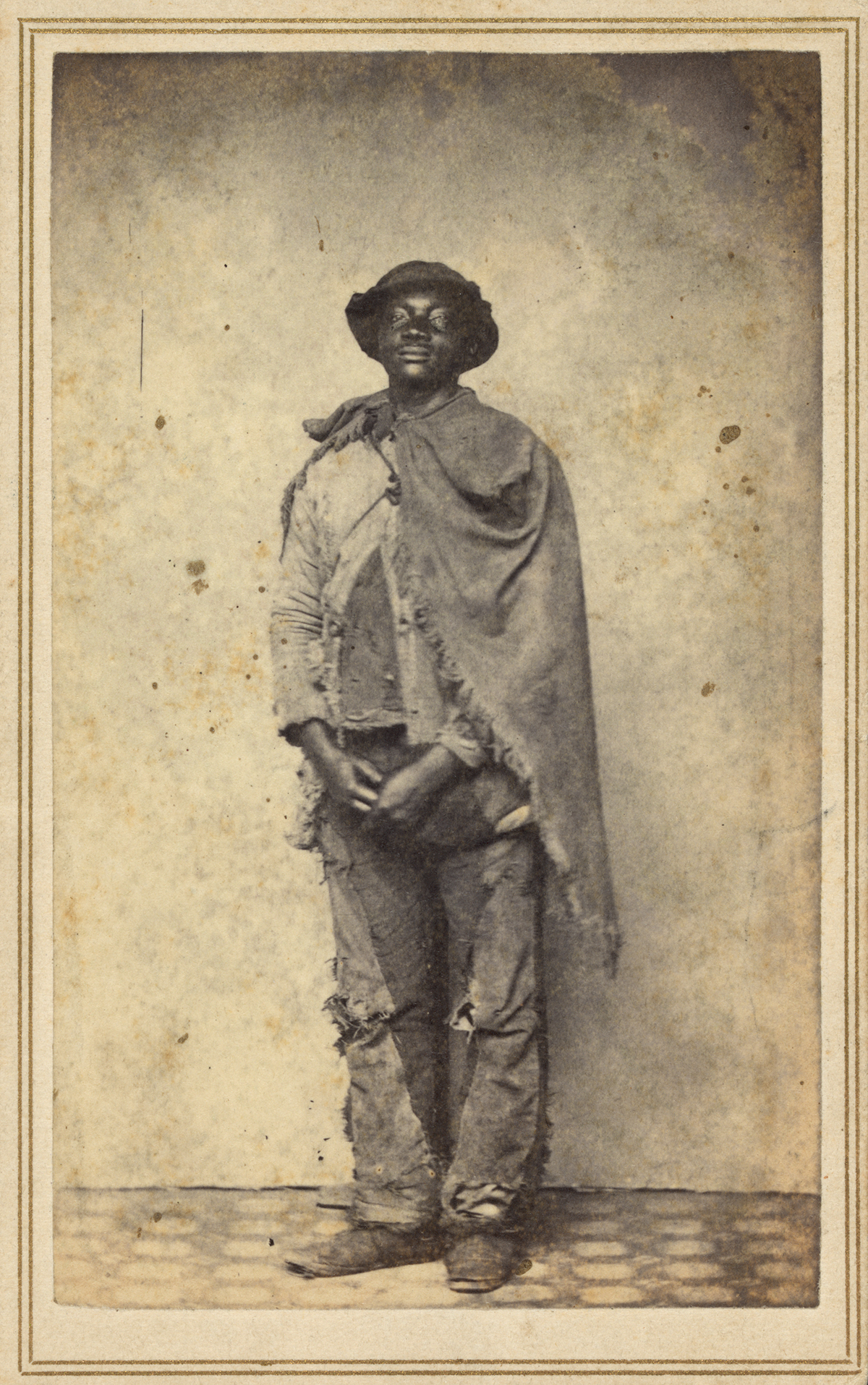

By the fall of 1863, Beaufort was busting at the seams. The little seaside town was overflowing with escaped and liberated slaves. Confederate deserters were everywhere. Throngs of Union sailors and soldiers (including many who were Black) and sick and wounded soldiers (a Union Army hospital was there) crowded the town’s old oyster shell and sand streets. Smugglers, shysters and war profiteers, of every loyalty, abounded.

Originally from Vermont, Rev. Comings had graduated from Oberlin College in 1838 and had been ordained there in 1841. He was at Oberlin at an extraordinary moment in the college’s history. In 1835, Oberlin admitted its first Black students, becoming one of the first colleges in the U.S. to do so.

Supporter Spotlight

To put that in perspective, I might note that was 116 years before the University of North Carolina admitted its first Black students.

Two years later, in 1837, Oberlin admitted women students for the first time, becoming the first coeducational college in the U.S. At the same time, the town of Oberlin was becoming a hotbed of anti-slavery activism.

To what degree Oberlin shaped Rev. Comings’ views on slavery, I do not know. But after finishing at the college’s seminary, his first pastorate was in Frederickstown, Ohio, where proponents of slavery attempted to blow up and burn his church because of his and his congregation’s anti-slavery views.

The Rev. Comings’ abolitionist beliefs also led him to Beaufort. In his and Sarah’s letters, we get a glimpse of wartime Beaufort and of a local history of Afro-Christianity that had defied slavery long before the Civil War.

We also get a fascinating look at the two missionaries, Elam and Sarah, their commitment to African American freedom and education, and also the limits of their commitment to racial equality.

These are some of the notes that I made as I read Elam and Sarah Comings’ letters at Oberlin College.

* * *

Rev. Comings to his wife Fanny, Nov. 6, 1863

He has left their home in East Berkshire, Vermont. On route to North Carolina, he learns where the American Missionary Association has assigned him. “I am to teach in Beaufort.”

Rev. Comings to Fanny, Nov 12, 1863

He and their daughter Sarah are in New Bern, 35 miles up the railroad line from Beaufort. They will take the train to Morehead City, then a ferry to Beaufort in the next day or two.

Rev. Comings to “my dear wife,” Nov. 16, 1863

He describes his first visit to one of Beaufort’s African American schools. The school is held in a local church, probably Purvis Chapel.

“As I entered the Ch(urch), I saw 150 (illegible) of all ages each with some book primer … And a few with scripture … books all eagerly trying to spell out the words. A few …could read the testament.” He notes: “The teachers were all blacks but a short time out of slavery.”

He also makes this observation with respect to the African American women that he meets in Beaufort:

“The women look as tho they have suffered (under slavery) by far more than the men. They look abject … and dejected … The great day will reveal many a story of shame and sorrow through which they have past. (sic). ”

Rev. Comings to Fanny and Eliza (their other daughter), Nov. 24, 1863

He describes a pastoral visit to a dying man in Beaufort. “He was a poor slave, and leaves two little children and a wife.”

He also reports that his students will largely be African Americans who had recently escaped from slavery, but he expects some white children, too. He mentions that some white adults have already showed up at the school’s night classes.

“Some 7 or 8 North Carolina white soldiers came to our evening schools to learn enough to write their names. They are deserted from the Rebels. They come in here on an average of about 10 per day(,) take the oath and join the Union army.”

Rev. Comings to “my dear wife” and Eliza, Nov. 23, 1863

He begins to realize how little he knows about the African American faith and spirituality during slavery. The Whipple School now has 235 students, but he is surprised how well the former slaves already know Scripture.

“It is a puzzle to me to see how they have got hold of the Bible so much, when never allowed to learn to read till they were free.”

Sarah Comings to “ma and sis,” Nov. 26, 1863

“The colored people are very kind to us and make us presents of apples, fish and other little gifts.” She reports that she picked flowers at Fort Macon and collected seashells at Cape Lookout.

Rev. Comings to Fanny and Eliza, Nov. 28, 1863

He is not accustomed to the coastal landscape. Everything is new to him: “Back of our house is a pretty grove of what they call ‘Live Oaks.’”

Rev. Comings to Eliza, Nov. 29, 1863

He presides at a funeral for the African American man he visited on Nov. 24. The funeral is held at a local home. The service begins with the kind of solemnity with which he is accustomed, but he is surprised when the mourners begin “singing, shouting, stamping and clapping.” He writes, apparently somewhat taken aback, “It was a joyful time to them.”

He recalled, “As I came down from the pulpit one great stout man got hold of my hand and squeezed it till it ached … and fairly lifted me up saying ‘Oh Brother I am happy, my soul is full!”

Rev. Comings to Eliza, Dec. 11, 1863

He describes where the AMA missionaries stay in Beaufort. “We live in an academy or boarding school building. In the basement story is a kitchen where we take our meals; the next floor above is a large school room now occupied by a school of the ‘poor white trash’ as they are here called, taught just now by a Mrs. Etheridge from Pa. In the next story are sleeping rooms … We have at present in our family 8 teachers including myself … The teachers work very hard in school and have little strength for anything else. I have an evening school 5 nights in the week for young men.”

Rev. Comings to “my dear fellow pilgrims,” Jan. 18, 1864

He has visited Newport, a village 10 miles west of Beaufort: “it has 6 stores … There is one hotel or boarding house containing two sleeping rooms, besides those occupied by the family. One blacksmith shop, one schoolhouse and there will soon be another when I get mine done for the blacks. There is also one stable large enough to contain two mules … On Broadway there are a good many houses, I guess nearly a dozen. And one of them is two stories high.”

Rev. Comings to Eliza, Jan. 24, 1864

He tells Fanny and Eliza that the former slaves in Beaufort are struggling to find housing. As they pour into town, they are bedding down in attics, hallways, porches and sheds.

He also reports a growing number of the sick. “For the last 3 weeks or so, our teachers have been strangely ill. This has made me anxious.” Sarah has also been ill.

Rev. Comings to Fanny and Eliza, Jan. 30, 1864

The Rev. Horace James, the Union army’s Superintendent of Negro Affairs in North Carolina, is visiting Beaufort. His wife is with him. According to the Rev. Comings, he and Horace James “regret that Mrs. James considers it `an impropriety’ to eat in a negro’s house.”

Mrs. James was far from unusual. Despite their anti-slavery beliefs, the northerners in wartime Beaufort — soldiers, civilians and missionaries — typically shared a sense of white superiority and Black inferiority.

Racial prejudice abounded. In his letters, Rev. Comings, for instance, occasionally referred to African Americans as “darkies.” Likewise, Sarah was genuinely committed to her Black students, but she also compared them to monkeys. Both referred to Black men and women in childlike terms.

Rev. Comings to Fanny, Feb. 8, 1864

He reports that Rebel troops attacked the Union outpost in Newport. He and Sarah fear the fate of a regiment from their home state, the 9th Vermont Infantry, that was stationed there.

The Vermonters retreated to Beaufort. “Some 25 sons of Vermont there fell killed and wounded on the first day … Seven wounded men are brought to our hospital here. I attended the funeral of one of them yesterday …There are more than 200, mostly women and children, thrown upon us … I have been obliged to take Sarah’s school room for them to occupy till the storm is past …”

Rev. Comings to Fanny, Feb. 29, 1864

Rumors of 40,000 rebel troops massing near New Bern have reached Beaufort. The town is in a panic. If New Bern falls, Beaufort would likely be next. (New Bern does not fall).

Rev. Comings to Fanny, Mar. 15, 1864

He seems beleaguered and worn out. He thinks he is “called” to return shortly to Vermont. “You think a great deal today no doubt of the deep waters through which we have past (sic),” he tells his wife.

He gives few details about the wellsprings of his discouragement, but he does mention one loss. “We are all today in deep mourning. One of our beloved teachers died yesterday at 4 bells. She was sick one week. We thought her in no danger till just before her death … Mrs. Carrie McGetchen of Maine.”

Death would soon become a daily occurrence. The great yellow fever epidemic of 1864 is just around the corner.

Rev. Comings to “dear ones at home,” Mar. 19, 1864

Since the recent Confederate attacks, he is spending a great deal of time visiting wounded and sick soldiers at Hammond Hospital, the Union army’s hospital in Beaufort. The hospital occupies a building that was formerly the Atlantic Hotel, a seaside resort. “Since the last excitement … my duties have been altogether too much for me to endure a great while … ” He says that he is hoping to leave Beaufort in April. Sarah wants to stay until June or July.

Rev. Comings to his Sunday school students, April 3, 1864

In gratitude for a donation to his work, he writes the children in his old Sunday school class in East Berkshire, Vermont. In that letter, he tells them how one group of African Americans recently escaped from the Confederacy and reached Beaufort.

“About 10 days ago, some 300 or more of our soldiers went about 40 miles from this in a gunboat, taking with them two small flat-boats, with the design of letting free a large number of slaves, who are kept in bondage.

“A terrible storm came on very soon, and the whole party came very near being lost in the sea. One colored man, who went to manage a flat-boat, was lost. Noble fellow! He would not abandon his boat not even to save his own life, as long as there was the least hope that he might land and give his brethren a chance to escape from slavery. Thus he gave of his life.

“Some of this party succeeded in landing and brought away all the slaves there were on two plantations. In all there 41 men women and children.”

He then informs the children that he used their donation to purchase clothes and other provisions for those people.

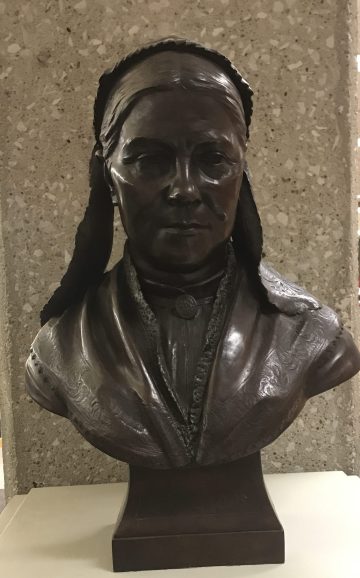

Sarah Comings to (illegible), April 10, 1864

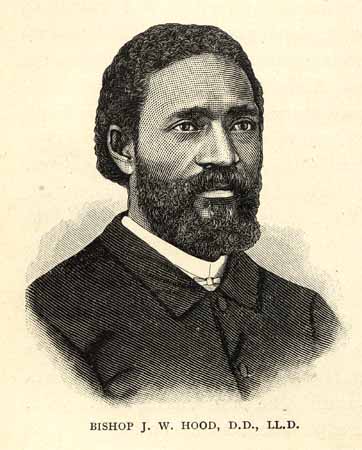

She praises the Rev. James Walker Hood for his sermon at a quarterly meeting of a local church — Purvis Chapel presumably.

Rev. Comings to Fanny, April 19, 1864

He is headed back to Vermont, but he is still in Beaufort and waiting for a ship north. He is still referring to African Americans as “darkies.”

* * *

“SHE MUST AND WOULD LEARN TO READ”

Along with the letters of Elam and Sarah Comings, Oberlin also had a clipping from an anti-slavery newspaper that mentioned the Rev. Comings and an African American woman in Beaufort.

That newspaper, The Morning Star, was published by Free Will Baptists in Dover, New Hampshire. The clipping does not include a date, but the newspaper’s editor, William Burr, visited Beaufort in March 1864.

I am not sure, but Burr apparently traveled with another anti-slavery activist, Ebenezer Knowlton, who was also involved with The Morning Star.

While in Beaufort, they met with Rev. Comings and toured the local African American schools. In the pages of The Morning Star, Knowlton later recounted a story that an African American woman in Beaufort told him about her struggle to learn to read and write while she was still an enslaved laborer.

Her story is very brief, but I think it has a special poignancy. The struggle of enslaved African Americans to get access to books, and most particularly the Bible, and the efforts of slaveholders to keep them from doing so, is one of the central themes in the history of American slavery.

Here is the excerpt from The Morning Star:

“Bro. Comings has just introduced me to a young woman, who he says is one of the most truthful, intelligent and really devoted, he has met among the freed slaves. She told me a few years ago she felt that she must and would learn to read – that she got visitors to read the labels on their trunks to her — then got a primer, which she used to hide under her bonnet in her bandbox.

“Her master in some way mistrusted that she had learned to read, and one day called her in great haste and said, `Go to the library and bring me the first volume of Hannah Moore.’

(Hannah Moore was an English poet, playwright and religious writer. She lived from 1745 to 1833).

“Being thrown off her guard by his unusual and excited manner, and fearing to disobey his order, she went and brought him the book.

“`There,’ said he, `Malinda, I thought you had learned to read, now I know you have.’ Then said Malinda to me, ‘he stripped me and whipped me almost to death!’

“`O Mr. Knowlton,’ said she, `can I ever be thankful enough … , that my children can now learn to read the Bible without being whipped to death for it?’”

Coastal Review is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.