Aquarist Michele Lamping devotes much of her winter — and has for the last 18 years — rehabilitating cold-stunned turtles at the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores. And this winter has been no different.

The coast experienced significant winter weather during three consecutive weekends in January, causing some cold-stunning, which happens when water temperatures rapidly drop. If the sea turtle is close to shore when the water gets too cold, too quickly, below 50 degrees, the turtle is unable to swim to the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream. The cold can cause the turtle to experience a hypothermic condition that renders them unable to properly swim.

Supporter Spotlight

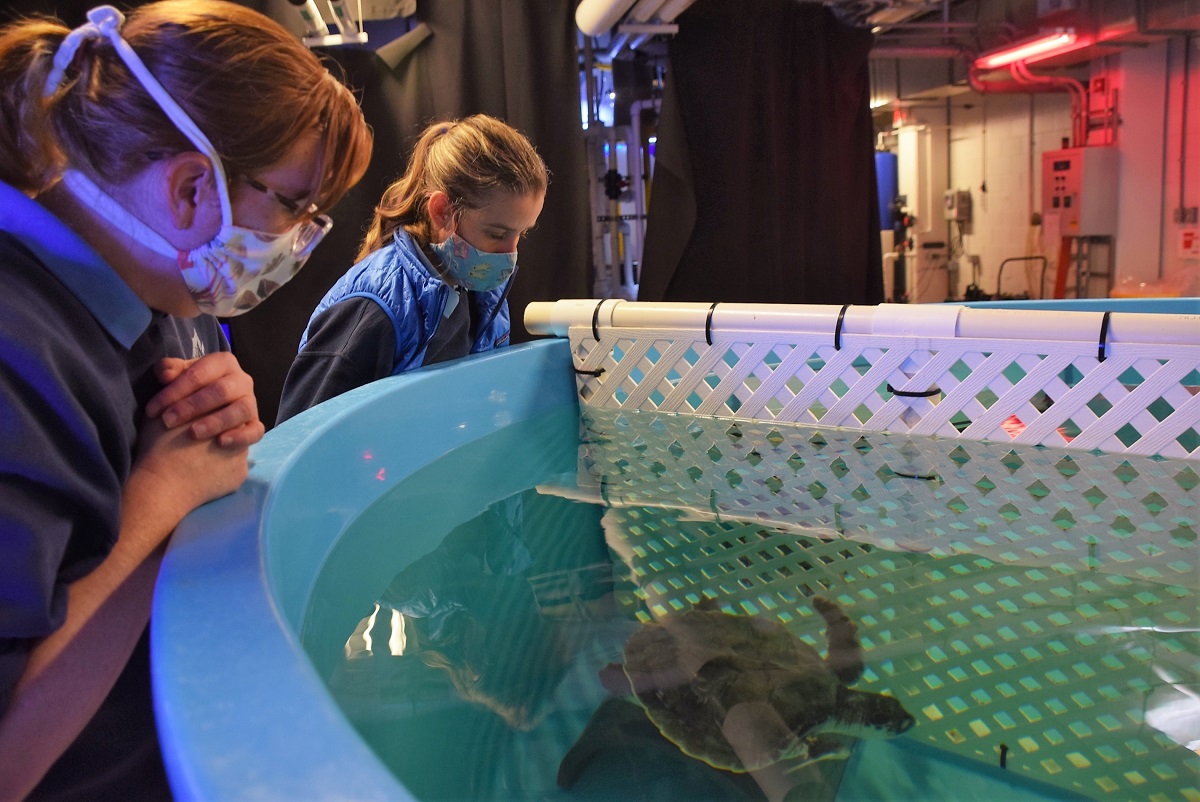

Lamping was helping rehabilitate 22 sea turtles in January, when Coastal Review was given a behind-the-tanks tour of the aquarium by Lamping and Shannon Kemp, communications social media specialist, to see where these cold-blooded marine reptiles are nursed back to health.

That day at the Pine Knoll Shores aquarium, there were 9 Kemp’s ridleys that had been flown here from Boston’s New England Aquarium, there were 12 total but three had already been rehabilitated and released. There was also a Kemp’s ridley from the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island and 10 green turtles and two loggerheads found in Carteret County waters.

Lamping said that the nine turtles still at the aquarium from Boston were cleared to be released, and were waiting on a boat that could take the turtles offshore. These turtles were found in Cape Cod and, thanks to a volunteer pilot program called Turtles Fly Too, were transported from Boston to Beaufort.

Nearly all sea turtles are in danger of extinction, “so it’s important that we save every one that we can,” Lamping explained about the coastwide effort. It’s difficult for a turtle to survive from the egg to a juvenile — that they’ve already made it that far is a big deal — and for them to die because it’s cold outside would be especially tragic.

“We want to give them every chance we can,” Lamping said. The staff here does all it can to help sea turtles reach reproductive maturity so their numbers can recover.

Supporter Spotlight

The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission heads up the rescue effort, Lamping said, and there’s a coastwide network of partners and volunteers that work every winter to save these turtles.

Wildlife Resources works with, in addition to the aquarium in Pine Knoll Shores, the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island’s Sea Turtle Assistance and Rehabilitation, or STAR, Center, the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher and Jennette’s Pier at Nags Head. The commission also works with the North Carolina State University Center For Marine Sciences and Technology, or CMAST, in Morehead City; N.C. State’s College of Veterinary Medicine; Cape Lookout and Cape Hatteras national seashores; the Karen Beasley Sea Turtle Rescue and Rehabilitation Center in Surf City; Hatteras Island Wildlife Rehabilitation; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; the National Marine Fisheries Service, also called NOAA Fisheries; and the Network for Endangered Sea Turtles, or N.E.S.T., a volunteer sea turtle rehabilitation center on the Outer Banks.

Most cold-stunned turtles that come in weigh about 5 to 10 pounds, and most are green turtles and Kemp’s ridleys.

“Smaller turtles are more susceptible to the cold,” Lamping said.

Small loggerheads are rarely affected because the youngest ones don’t spend time in inshore waters, unlike the larger juveniles.

Lamping said the first cold-stunned turtles this season arrived in early January. She said that Pine Knoll Shores normally has about 100 turtles pass through every year, but not all turtles are with her for rehabilitation from start to finish. As of Tuesday, the aquarium had taken in about 26 cold-stunned turtles so far this winter.

Wildlife Resources officials and National Park Service rangers track the weather so they can find cold-stunned turtles. They know when and where temperatures will be low enough for cold-stunning, so rangers and volunteers patrol these areas for stunned turtles. When a person finds a cold-stunned turtle, they typically contact one of the sea turtle rehabilitation centers, Lamping said.

Sarah A. Finn, coastal wildlife diversity biologist with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, told Coastal Review that as of Tuesday, the total to date is 151 cold stuns observed in North Carolina for the 2021-22 season.

Of those, 91 were alive and taken to rehabilitation centers, she said. The commission also has about a dozen turtles that have been cleared by the veterinary team and are awaiting the next boat ride to the Gulf Stream.

In an earlier email interview, Finn said that 15 cold-stunned turtles died soon after discovery and 17 have been released.

“We typically see between 100-200 cold stunned turtles every year in North Carolina, but it varies (in 2016 we saw nearly 2,000 cold stunned turtles). We see most cold stuns show up in the larger inshore water bodies: Pamlico Sound near Hatteras and Ocracoke, and Cape Lookout. Most cold stunned turtles we see are juvenile green sea turtles,” she said.

Finn explained that cold-stunning is a natural cause of stranding for sea turtles and the commission sees some level of cold-stunning every year. The timing and severity of the mass stranding depends on many factors, including variations in temperature, timing and duration of the first seasonal cold snap, cycles of rewarming, wind direction and other factors.

Finn said that the commission can typically predict with some level of certainty when cold stuns will begin showing up for the season, they can just never tell how many.

“Just after Thanksgiving, there was a cold snap and we had a handful of cold stuns come in. Then it was relatively warm again until January, so we didn’t see any for a while,” Finn said in the email. “We saw the majority of cold stuns during January 11-12, January 18, and January 22-24. Weather plays a role beyond just cold air, as wind direction is a big factor that determines if the cold stunned turtles wash ashore in an area where they can be observed and also bad weather and higher tides can prevent getting to these locations.”

The Wildlife Resources Commission allows trained volunteers and cooperators respond to stranded turtles in North Carolina, Finn said.

When live, cold-stunned turtles are found, the responder collects measurements, checks for tags and the turtle is transported to the nearest permitted rehabilitation facility. Commission staff collect all the data for stranded turtles in North Carolina and maintain a database that’s shared with NOAA Fisheries.

When the turtle is ready to be returned to the ocean, releases can take various forms, depending on the time of year, how many turtles are being released, the availability of vessels and offshore weather, Finn said.

“The length of time needed for rehabilitation can vary from relatively short (days-weeks) for uncomplicated cases, to several months or rarely even years for those that may develop secondary complications,” Finn said.

During the winter months, commission staff organize offshore releases in warmer waters near the Gulf Stream, usually partnering with institutions that have research vessels with planned offshore trips, such as CMAST, the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort or the Coast Guard.

“Occasionally when we have many turtles that are cleared for release, but unfavorable marine conditions prevent offshore releases, we have coordinated with South Carolina, Georgia or Florida to organize transport to the nearest beach from which we can release (with warm enough water). When coastal water temperatures are warmer in the late spring through early fall, we will release turtles directly from the beach,” Finn said.

Amber Hitt, manager of the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island’s STAR Center, told Coastal Review that, as of Tuesday, they’ve had 50 to 60 cold-stunned sea turtles come through their doors this winter. Their cold-stun season runs November to February.

“We get turtles mainly from Avon to Ocracoke, but could also get them from Nags Head to Corolla – Just depends on where the turtles are when it starts to get cold,” Hitt said in an earlier interview. “We could see anywhere from 30-600 turtles; no two years are the same and it varies based on weather throughout the year.”

She said that when the temperature gradually drops in the fall and winter, they see fewer turtles. “When we have the rapid drops in temperature where we go from summer to winter immediately — that is usually when we see those higher volumes of patients.”

Although there were three significant winter weather events in January, the STAR Center didn’t have a large volume of intakes.

“We did see a few higher-number days, but for the most part the turtles seemed to strand in smaller batches this year. There have been years where we could see 80-90 intakes in one day, but this year I think our highest intake day was around 10-12 in one day,” she said.

When the STAR Center get calls or when volunteers go out during winter months looking for any stranded turtles, “we arrange for trained volunteers to transport the turtles to STAR Center from wherever they are located,” Hitt said. They usually work with N.E.S.T. to have the turtles brought the the center. N.E.S.T. has a stranding hotline number, 252-441-8622, which is monitored around the clock.

Once a sea turtle is at the STAR Center, it is examined for any wounds, and veterinarians collect blood samples to see what vitamins and fluids they need to replenish their systems. Then they gradually warm the turtles in rooms where temperatures can be controlled until their body temperature reaches about 70 degrees, at which time they are ready for admission into the STAR Center, she said.

“When they are warm, they are swim tested and we start feeding them so that we can maintain or build their body condition back up to a stable weight. Once cleared of any illnesses, wounds healed, or they are more stable – they can be tagged and cleared for release,” Hitt said.

“Turtles that are cleared for release during the winter months need a ride out to warmer waters,” Hitt said. “In the past we have had local fisherman and U.S. Coast Guard Stations take turtles out to the Gulf Stream where the water is nice and toasty for the winter months. If turtles are in rehabilitation for a little longer and are deemed releasable in the spring/summer months, we look at local water temperatures to see if we are able to release locally and usually invite the public when possible.”

Christian Legner, a member of N.E.S.T. board of directors, said last week that most of the cold-stunned turtles they see are from south of Oregon Inlet, and the bulk of those are most often found between Rodanthe and Hatteras.

N.E.S.T. is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation and protection of the habitats and migration routes of sea turtles and other marine animals on the Outer Banks.

“N.E.S.T. volunteers and National Park Service staff have sent roughly 62 live turtles to the STAR Center for rehabilitation from Nov 1, 2021, to today,” she said. There were no updates as of Tuesday.

The average number of turtles each year can vary, from quite low numbers to hundreds.

She added that the bulk of the turtles were found and admitted in January, with about 46 during the month.

Because so many cold-stunned turtles are found on Hatteras Island, N.E.S.T. has set up an intake facility there where turtles are brought in by patrol volunteers, while processing volunteers fill out stranding forms with data including assigned ID numbers, measurements, notes about injuries and locations found, Legner said.

“Once the data is taken, the information is sent with each turtle to the STAR Center for medical intake. The turtles all travel to STAR on the same day they were found,” she said.

In the winter, releases are usually by boat so that the turtles, which are usually all juveniles, can be transported closer to the Gulf Stream and warmer waters. “We partner with the U.S. Coast Guard, charter fishing vessels, and sometimes birding trip charters on the Stormy Petrel II,” Legner said.

Like STAR, if a turtle is still in rehabilitation until the waters warm up, the Roanoke Island aquarium and N.E.S.T. work with the National Park Service to coordinate beach releases, where the public is invited to learn a bit about sea turtles and cheer them on as they depart, Legner added.

Kathy Zagzebski, executive director of the Karen Beasley Sea Turtle Rescue and Rehabilitation Center in Surf City, said Feb. 9 that the center had admitted 30 cold-stunned turtles so far this year. Of those, 13 were from Massachusetts and 17 were from North Carolina. Those from North Carolina were from the Cape Lookout area, except one from Carolina Beach.

There have been no new cold-stunned turtles admitted since Feb.9, Zagzebski told Coastal Review Tuesday in an update.

“This year was an average year as far as the number of cold stunned turtles we received. On average, we tend to admit 18-20 cold stunned turtles in January. It varies significantly, however, We’ve had as few as on and as many as 58 turtles admitted during this month,” she said Tuesday.

The sea turtle hospital staff weigh and take measurements as the sea turtles are admitted, the same process as that of the other rehabilitation centers, Zagzebski said in an earlier interview.

“Weights are important in calculating fluids and medication. We perform an external body exam to look for any wounds, injuries, or other conditions. We take a diagnostic blood sample to assess dehydration and other conditions. We often take radiographs (X-rays) to look for broken bones or pneumonia,” she said. “We upload all the information to our patient medical records database so our veterinarian can see the results.”

The treatment may include fluids, antibiotics and other medications.

“We keep the turtles in very low water or on wet towels initially, then gradually introduce them to deeper water. As they start to recover, we begin to offer food. For cold-stunned turtles, there is also a warming period that occurs over several days,” she said.

Once a turtle is rehabilitated and healthy and the veterinarian has approved them for release, the sea turtle hospital plans a release.

“This is always a joyous event to watch the turtles return to the ocean. Some releases are held from shore, especially locally in Surf City. At this time of year, however, the water is too cold. In these cases, we partner with other organizations and businesses to arrange an offshore release in the warm waters of the Gulf Stream,” Zagzebski added.

Zagzebski asks that if you see a sick, injured, or cold-stunned sea turtle on the beach, keep your distance and call the Wildlife Resources Commission Turtle Hotline at 252-241-7367, or your area sea turtle rescue group.

“Please do not pick up the turtle or put it back in the water. Please do not try to warm up the turtle. It takes special training to safely handle and rehabilitate a sea turtle so it can be released back to the wild,” she said. “Other ways to help: Keep plastic off the beach and out of the ocean. Plastic looks like food to a hungry sea turtle! During sea turtle nesting season, fill in holes on the beach when you are done with them and bring in beach furniture so they don’t cause a hazard to a nesting turtle.”