Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

Gates County is yet another fascinating county that emerged from the original Albemarle settlements.

Supporter Spotlight

Its rural character, plantation history and natural beauty make it similar to other northeastern counties such as Chowan, Pasquotank and Camden.

Gates also has had to adapt to the decline of agriculture and find its place on the outskirts of metropolitan Virginia like all the northeastern counties. But Gates has a number of famous residents, plantation homes and a state park that makes it a worthy subject.

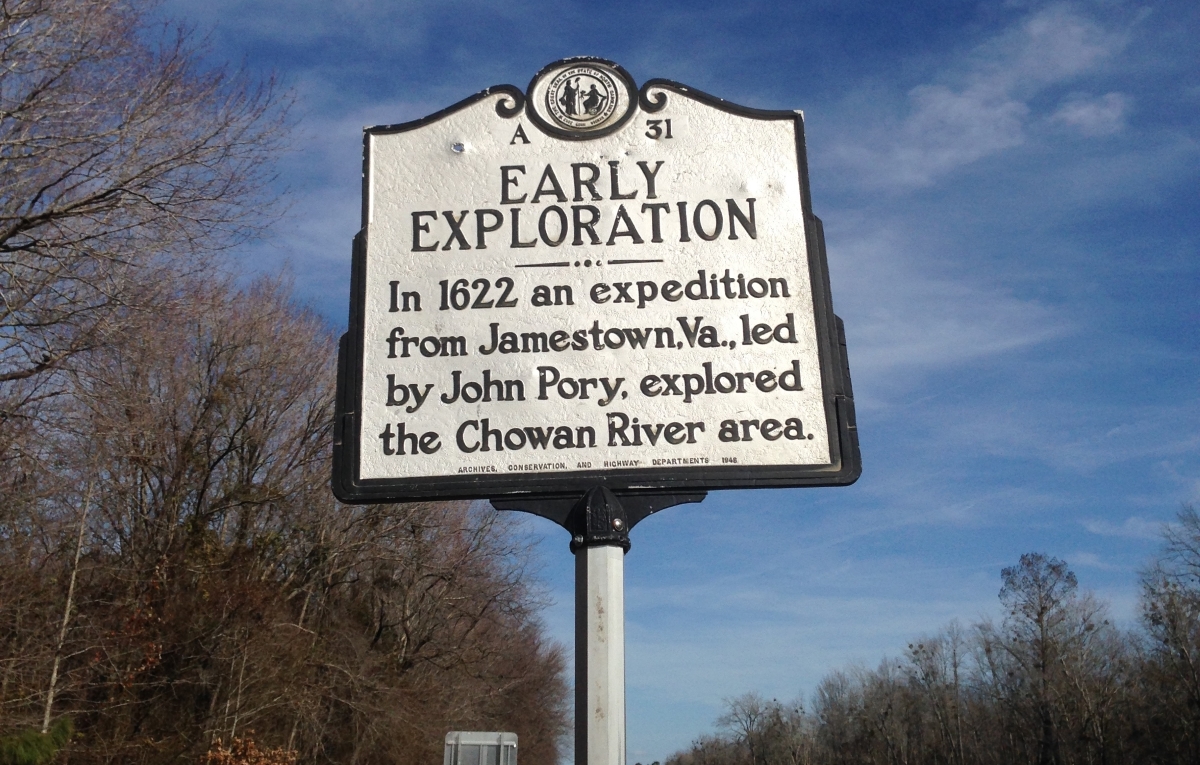

The area that is now Gates County was originally the home of the Chowanoke Native Americans. The Chowanoke were a sizable group whom Europeans eventually forced onto a reservation, which was dissolved by 1821. After the journey of John Pory down the Chowan River in 1622, Europeans began to settle in the area. Traders bought Native American land and were followed by farmers who grew corn and tobacco. During much of the 17th century, the current county made up the northwestern frontier of North Carolina.

Gates County was formed in 1779 and was named after Revolutionary War general Horatio Gates. According to David Leroy Corbitt, author of “The Formation of the North Carolina Counties, 1663-1943,” the county was formed from the northeastern section of Hertford County and the northern sections of Chowan and Perquimans counties.

The county’s soil and proximity to the markets of Virginia made it a center for tobacco cultivation in the antebellum period. Planters built sizable homes such as Buckland in 1795 and Elmwood Plantation in 1822.

Supporter Spotlight

They also constructed mills that ground corn and powered saws to process the county’s sizable lumber stands. One of these mills created the landscape that later became Merchants Millpond State Park, one of only two state parks in North Carolina in the Albemarle region.

The wealth of Gates County planters came at the expense of the county’s sizable enslaved population. According to the 1860 Hergesheimer map, 48.3% of Gates County’s population was enslaved in that year, the 18th highest total in the state. The Hergesheimer map shows the distribution of the slave population of the southern United States.

Along with a large number of slaves, Gates County also had a robust free African American population, partly because of the county’s border location. In his history of free African Americans in North Carolina, John Hope Franklin noted that “In the counties bordering on Virginia and South Carolina were to be found a large number of free Negroes whose very presence in these areas bespoke the more liberal treatment of free Negroes in North Carolina than in the neighboring states.”

The 1860 census counted 361 free African Americans in Gates County. They were significant members of the community and held a wide variety of professions such as carpenters, blacksmiths and coopers. But free African Americans also held a precarious place in North Carolina society. Their activities were restricted, they had few legal rights, and were constantly viewed with distrust by white society.

Gates County escaped the Civil War with little war-related damage. The county’s rural location was not strategic to the war aims of either the Union or the Confederacy, and so it avoided major battles or raids. But following the war, the county had to rebuild its economy.

Peanut cultivation flourished in the county along with truck farming of fruits and vegetables and livestock. Gatesville, originally incorporated in 1830, served as the only sizable community in the county. The hallmark of the town was and is the Gates County Courthouse, built in 1836 and enlarged in 1904, which became known for its Greek Revival details and cast-iron railing as noted by Catherine W. Cockshutt in her nomination of the building for the National Register of Historic Places.

Gates County also played a role in Reconstruction. African Americans and white Republicans reshaped county government and filled numerous political offices. One of the county’s residents, John Wallace, left the county for Florida and served as a Republican state senator and representative. He later became known to historians for a controversial book which, according to historian James C. Clark, in “was critical of his fellow blacks and Radical Republicans, and frequently complimentary of white conservation (conservative) Democrats.” The true authorship of the book remains in question.

African Americans in North Carolina were disenfranchised following the white supremacy campaigns of 1898 and 1900. They still played a role in the economy and society of Gates County, however. A prominent example of this engagement was the establishment of Rosenwald Schools, centers of African American education across the South funded by Sears President Julius Rosenwald. Gates County was home to seven Rosenwald Schools according to a 1930 report from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. Two are still standing, most notably the Reid’s Grove School, which is on the National Register of Historic Places.

In the 20th century, Gates County was home to a number of prominent North Carolinians. Thad Eure (1899-1993), born in the southern part of the county, was the North Carolina Secretary of State for 53 years and holds the title of longest-tenured elected office holder in American history.

Herman Riddick was an influential African American football coach at what later became North Carolina Central University, coaching for twenty seasons according to Central’s Athletics Hall of Fame website.

Calvin Earl, famed African American singer and educator on spirituals, is also from Gatesville.

Today, Gates County is a rural curiosity on the border with Virginia. It is the second-smallest county by population in the Albemarle region behind Camden County, and its only town, Gatesville, has fewer than 400 people. The county is removed from whatever traffic may be associated with interstate construction on U.S. 17 or the mid-Currituck bridge. But Gates County has room for growth, nonetheless.

Merchants Millpond attracts a young visitor base with its trails and paddling opportunities. As noted in Indian Country Today, the Chowanoke Native Americans have started purchasing land in the county and hope to open a cultural center. There is also the possibility of development from Hampton Roads, with Suffolk, population 90,000, only about 10 miles away from the county’s northern border.

Like the counties to its east, Gates County will have to tackle the question of whether it will become a satellite of southeast Virginia or will continue the rural character that has defined it for centuries.