A recently published study examining the effects of Hurricane Florence on the lower Neuse River reveals how one river system adapted to the type of coastal storm forecasted to be the norm of future hurricane seasons.

Jonathan Phillips, an adjunct professor in East Carolina University’s Department of Geography, Planning and Environment, began examining the lower Neuse and its estuarine sites a few days after Hurricane Florence trudged through eastern North Carolina in September 2018.

Supporter Spotlight

Phillips, who also holds the title professor emeritus at the University of Kentucky, focused in the study, “Geomorphic impacts of Hurricane Florence on the lower Neuse River: Portents and particulars,” on the storm’s effects on the river’s physical landscape, including shoreline bluffs, and the Neuse estuary, including ravine swamps and tributary swamps along the river.

What he found is that the river, specifically the largely undeveloped stretch between Kinston and New Bern, and its accompanying swamps adapted and recovered after the storm.

“There’s absolutely no reason to intervene in the recovery of the undeveloped shorelines,” Phillips said. “Their ecosystem services are just as good now as they were before the storm. They’re providing the same functions and values.”

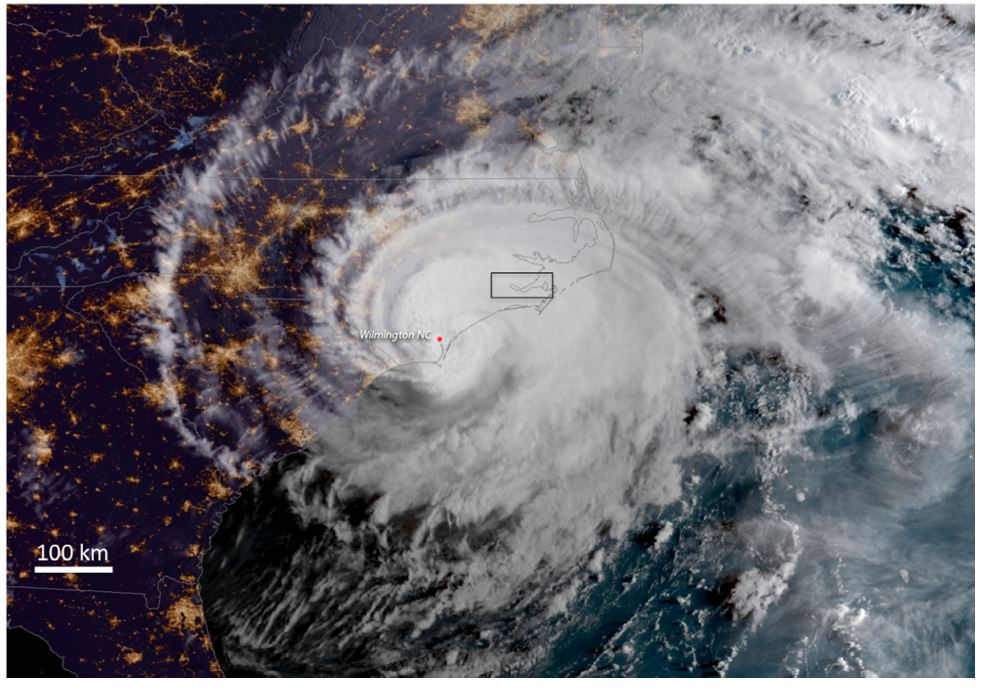

Though Hurricane Florence was a Category 1 on the Saffir-Sampson Hurricane Wind Scale when it made landfall near Wrightsville Beach Sept. 14, 2018, it quickly broke records, becoming the wettest tropical cyclone on record in the Carolinas.

The combination of torrential rainfall, storm surge and wave action beat the already eroding estuarine shoreline bluffs in the lower Neuse, an area Phillips examined after hurricanes Bertha and Fran in 1996.

Supporter Spotlight

Those shorelines would continue to erode without the impacts from Hurricane Florence, Phillips said. Such erosion has been occurring since at least the 1970s, according to scientific literature, he said.

“What was different about Florence was, at least at the sites I looked at, was an unprecedented rate of erosion in terms of retreats of those bluffs — more than any other storm or single recorded incident,” Philips said. “One of the characteristics that happened during Florence was because the water was so high for so long. Usually, in terms of its effects on any particular location, a hurricane comes and goes in half a day or less. In this case, in the lower Neuse area, you had high winds, not hurricane winds, but high winds and high water for about four days.”

High waters and winds occurring for an extended period of time enabled what Phillips referred to as “wave attack” both higher up on the bluff and for a longer-than-normal period of time.

The result: an average of about 40 feet worth of shoreline retreat.

“When you’re talking about 12 meters, or 40 feet, of lateral retreat with bluffs that are typically about 10 meters — 30 to 35 feet high — that’s a lot of sediment,” Phillips said.

That sediment ended up in the ravine swamps, transforming them from the perpetually flooded swamps with a muddy, organic base they were prior to Hurricane Florence to sand-filled swamps.

Sand loss on the bluffs created what Phillips refers to as a “storm bench” or “storm platform,” which is formed when a layer of sand over top of a tight, clay base, erodes away.

In eastern North Carolina, Phillips said, it doesn’t take long for some kind of vegetation to colonize on most any surface.

New vegetation is growing in the sand that has filled some of the ravine swamps. It’s also growing on the storm benches.

“These systems, in terms of their geomorphology and hydrology and ecology are adapted to storms,” Phillips said. “They’re created by storms. They’re getting to experience tropical cyclones and nor’easters periodically. The difference is now they’re likely to experience more and more powerful and different in terms of the slower moving, wetter storms.”

He said that, in spite of Hurricane Florence’s record-breaking storm surge and the high stream flows created by the storm, environmentally speaking, there were no major geomorphic impacts to the lower river from Contentnea Creek, a major tributary of the Neuse, down to New Bern.

“There was very little change and that was because those systems have evolved during a period of sea level rise and they’ve developed in such a way that they’re perfectly suited to handle a lot of water coming from upstream or downstream or both,” Phillips said.

“What you’ve got along most of that corridor is, rather than your classic complex of channels that flow all the time, ones that flow only sometime, wetland depressions, and wetlands that typically have water flow through them so it’s adapted to be able to temporarily store large amounts of water and release it gradually downstream through all that complex of channels and wetlands and depressions,” he continued. “The fact that it was able to do that during Floyd is attributable to the fact that those wetlands have been protected by Section 404 (of the Clean Water Act) by incorporating a number of those swamps for the Neuse River Gamelands.”

The storm’s impact on human infrastructure along the river was substantial.

Hurricane Florence was the third storm — following Matthew in 2016 and Floyd in 1991 — to cause major flooding in a handful of North Carolina’s coastal plain river basins, exposing the vulnerabilities of communities within those flood plains.

Responses to mitigating impacts to those communities from similar storms in the future have included government buyouts.

Nearly 650 properties damaged by hurricanes Matthew and Florence had by December 2019 been acquired in buyouts, according to North Carolina Sea Grant.

Academic studies since Florence have looked at ways to implement natural infrastructure, such as stream restoration, along the riverine landscape to abate flooding.

“In terms of planning and management I feel like we shouldn’t be like the proverbial generals fighting the last war,” Phillips said. “We have to be ready for new and different things and Florence was unprecedented in terms of the duration of the winds and the amount of water involved. But, we can’t really assume that other storms are going to be like Florence now. We’ve just got to be ready for anything basically.”