Over the last several years, I have written a series of photo essays focusing on Charles A. Farrell’s photographs of fishing communities on the North Carolina coast in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

This is the 10th and last essay that I am devoting to Farrell’s remarkable collection of photographs.

Supporter Spotlight

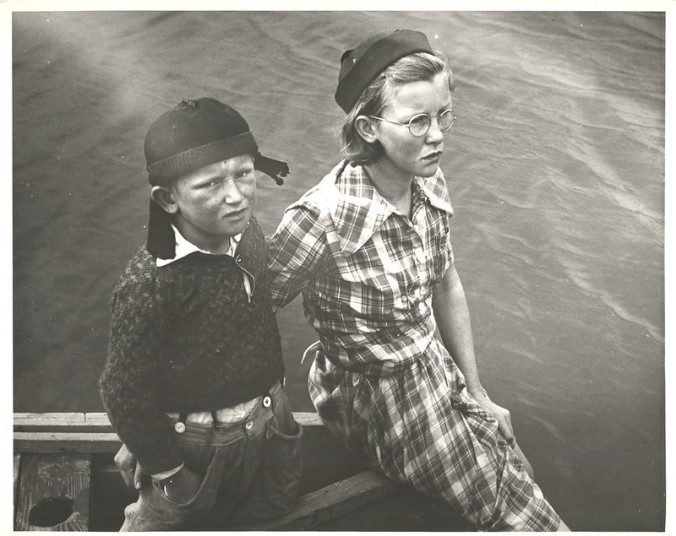

In this essay, I will showcase photographs that he took on Cedar Island, Wanchese, Manns Harbor and one or two other fishing villages that I have not previously featured in this series, as well as a few old favorites.

But I mainly want to do something else, and it is something that maybe I should have done when I began this series. At that time, I suppose that I was afraid that it would distract from the people and places in his photographs.

But now I think it is time to explain why Charles Farrell never published his extraordinary photographs and why he and his photographs were forgotten for so many years.

* * *

That story goes back to the 1930s when Farrell, and often his wife Anne, began traveling the backroads of the North Carolina coast.

Supporter Spotlight

At that time, they lived in Greensboro, where they ran an art supply business, camera store and photography studio called The Art Shop. But whenever they could spare the time, they headed east to the coast.

How Charles Farrell came to feel so akin to the state’s fishing communities has never been clear to me. His father was an itinerant tintype photographer who, after the Civil War, traveled from hamlet to hamlet, making portraits for people who had often never seen a camera before.

I have wondered if Charles’ father used to visit the fishing villages that his son later grew so entranced by, and if his father’s stories later led Charles to visit those communities and fall under their spell. But of course, I don’t really know.

What I do know though is that Charles kept returning to those fishing communities again and again, as if he was searching for some lost part of himself by the sea.

Beginning in 1936 or 1937, he began documenting life and work in dozens of the state’s fishing communities.

Those of you who live on or often visit the North Carolina coast will recognize the names of some of the places that he visited — Beaufort, Southport, Nags Head, Manteo, Edenton and others.

You may or may not recognize the names of some of the other places he visited: Terrapin Point, Colerain, Brown’s Island, Marines, Stumpy Point and others that barely exist anymore, though some of them were among the state’s most important centers of commercial fishing in the 1930s.

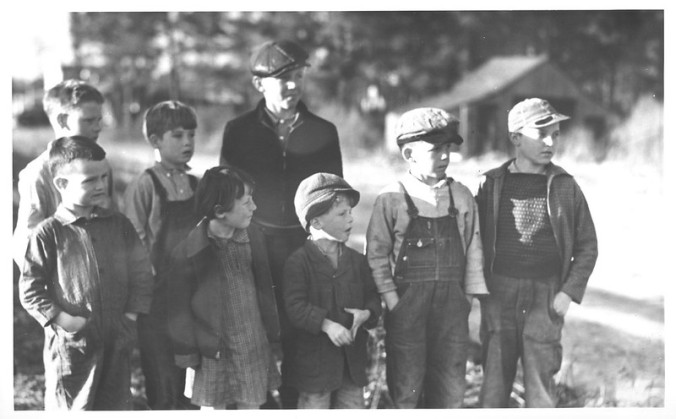

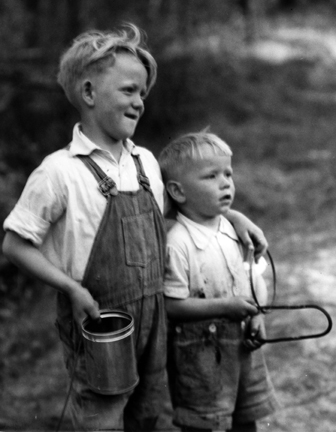

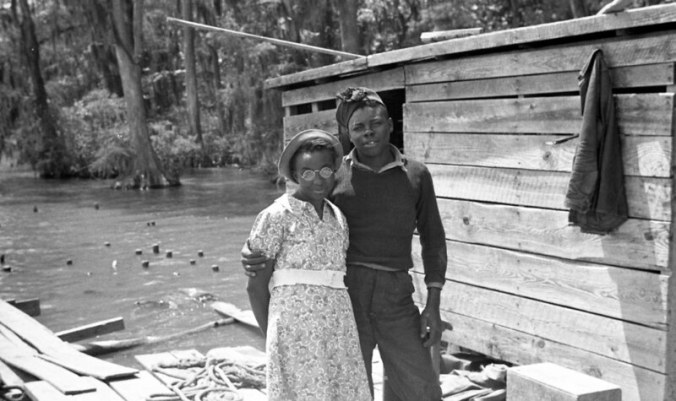

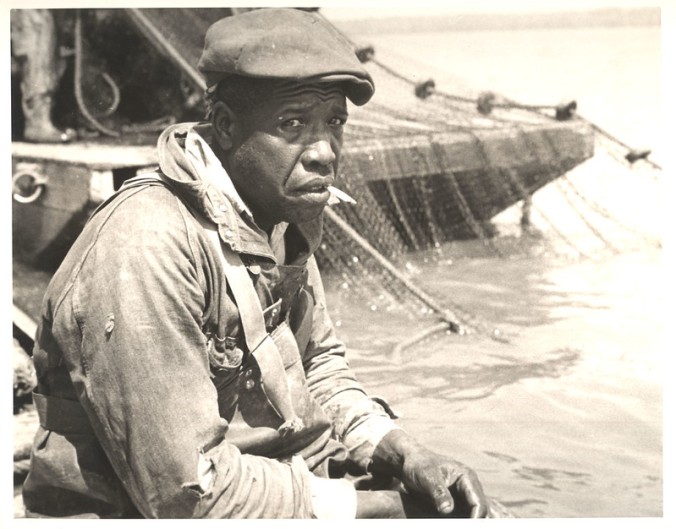

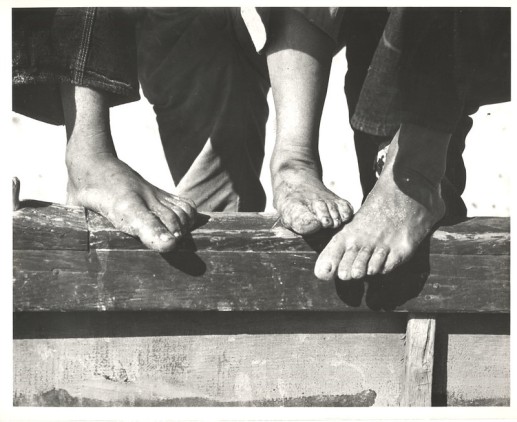

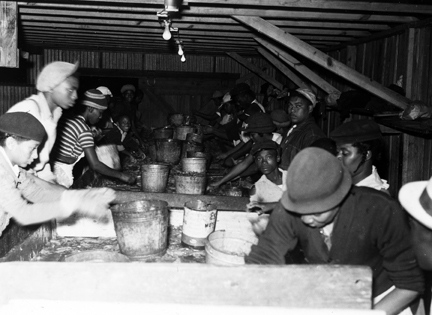

The most compelling thing about Farrell’s work to me has always been that he had a special eye for those who usually go unseen in historical photographs of North Carolina’s fishing communities: women, people of color, children and the aged.

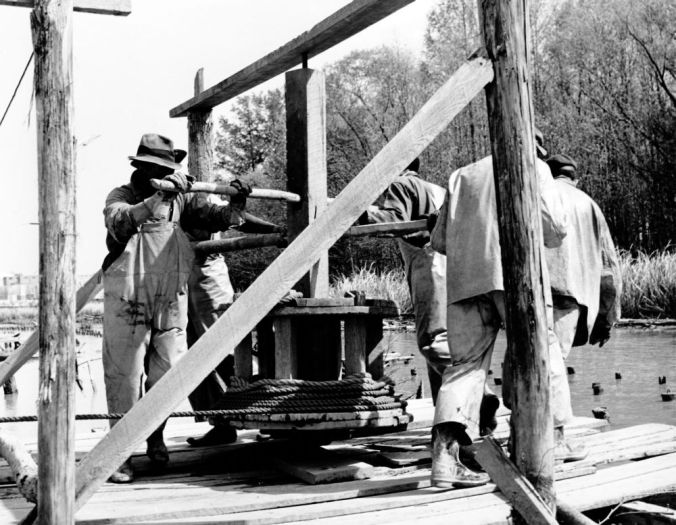

In addition, Farrell carried his camera places that other photographers did not go: the insides of canneries and fish houses, the mess halls and engine rooms of fishing boats, salting sheds, net lofts, bunk houses and wherever else he found those who made their living from the sea.

Now preserved at the State Archives in Raleigh, his photographs make up the fullest visual portrait of North Carolina’s fishing communities in the first half of the 20th century in existence.

* * *

In the late 1930s, Farrell signed a contract with William Couch, the editor-in-chief at the University of North Carolina Press, to publish a book that would feature his photographs of North Carolina’s fishing communities.

Farrell never finished that book, however. The photographs were never published in a book or anywhere else. For decades, the prints and negatives remained in boxes, all but forgotten, presumably either at the Farrells’ home or shop in Greensboro.

As gifted as he was as a photographer, Farrell soon realized that he had not developed his talents as a writer and the book that he and Couch envisioned was to have been a combination of photographs and writing.

But something else was going on, too, which I realized while I was doing background research on Farrell’s life in preparation for writing the first photo essay in this series.

That photo essay was called “An Eye for Mullet: The Photographs of Charles A. Farrell.” In that first part of the series, I focused on just one group of photographs, which Farrell took at a mullet fishermen’s camp on Browns Island, in Onslow County, in 1938.

That photo-essay originally appeared in Southern Cultures, a scholarly journal published by the Center for the Study of the American South at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill.

What I discovered was that Farrell was struggling with what would eventually become an incapacitating mental illness while he was working on his book of coastal photographs.

I learned something of his illness from his family. I spoke with his younger sister, one of his sons and one of his nephews. All generously shared their recollections of Charles Farrell with me. I appreciated this especially because, at least for his son, it was painful to do so.

I also learned a good deal about Farrell’s mental illness from a collection of the family’s letters, diaries and other records that has been preserved at the Greensboro Historical Museum.

I still do not fully understand the nature of his ailment, however. All I know for sure is that he struggled to write the book in the early 1940s, when he first tried to put pen to paper. That is evident in a series of correspondence between Farrell and his editors that is preserved at the Southern Historical Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill.

But the fate of Farrell’s coastal photographs was really sealed a few years later, in 1948, when he was hospitalized in Greensboro.

While in the hospital, Charles Farrell underwent a neurosurgical treatment called a transorbital lobotomy.

They were better known as “icepick lobotomies.” The first one in the U.S., which was performed at George Washington University in 1936, was actually done with an icepick.

In performing the procedures, surgeons severed the connections to the brain’s prefrontal cortex by driving a surgical tool through the patient’s eye socket with a small mallet.

Most Americans know of lobotomies, if they know of them at all, one of two ways. Some recall that Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of President John F. Kennedy, had a prefrontal lobotomy in 1941. She was incapacitated the rest of her life, and the Kennedy family largely kept her out of the public eye.

Others remember the 1975 movie “One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” which was based on Ken Kesey’s wonderful book of the same name.

At the movie’s end, Randall McMurphy, played by Jack Nicholson, is forced against his will to have a lobotomy to repress his rebellion against the asylum in which he was being held.

The peak year for the procedure’s use in the U.S. was 1949, just after Charles Farrell’s surgery. In that year, surgeons performed more than 5,000 transorbital lobotomies in the U.S.

Particularly in the 1940s and 1950s, psychiatrists looked to the procedure for treating a host of mental illnesses for which they had no effective treatments at the time. Those mental illnesses ranged from schizophrenia to alcoholism.

The neurosurgeon most responsible for the procedure’s popularity in the U.S., Dr. Walter Freeman, referred to the desired effect as “surgically induced childhood.” Most patients, including Farrell, became passive, emotionally blunted and limited in their intellectual range.

The efficacy of transorbital lobotomies was widely debated. So was their morality. As early as 1950, some countries had banned them, considering them both ineffective and inhumane.

Reports of abuses of the procedure were also widespread.

In a sign of the mental health profession’s own maladies at that time, a strikingly disproportionate percentage of the procedures in the U.S. and other Western nations was done on women, often with an eye toward making them more docile and compliant.

There is also some evidence that Dr. Freeman, at least, was more inclined to perform transorbital lobotomies on African American patients than on white patients.

I have also read accounts of surgeons using icepick lobotomies as a “treatment” for same-sex attraction. In a case I recently discovered near my home, a psychiatrist apparently also used the procedure in an unsuccessful attempt to “cure” a decorated World War II veteran of his affection for cross dressing.

What led Farrell’s family and physicians to resort to a transorbital lobotomy is not clear to me. His surviving family, who were too young at the time to know for sure, suspect alcohol was involved.

But if the nature of his struggles is still mysterious, I do know this: Charles Farrell’s life as a photographer and artist ended on the day of his surgery.

When I spoke with his family, they told me that he lived a quiet, rather passive and apparently untroubled existence for the rest of his life. Unlike Rosemary Kennedy, he was never institutionalized, however. He could still speak intelligibly, and he still got around on his own a little.

When I talked with his younger sister, she recalled that he even sometimes caught a city bus and went downtown to visit with old friends.

After her husband’s surgery, Anne Farrell ran The Art Shop until it went out of business in the early 1960s. She and Charles both lived until 1977. He died at the age of 84, and she was a year younger.

After their deaths, their son Roger Farrell, a distinguished professor of mathematics at Cornell, donated more than a thousand of Charles’ photographs to the State Archives of North Carolina. Roger and I talked about his father not long before he passed away in 2017 at the age of 88.

* * *

When he took these photographs, we now know, Farrell was a broken man or, at the very least, a man on the edge of breaking.

I wish he could have known how much his photographs would come to mean to those of us seeking to understand North Carolina’s coastal past.

I also wish that he could have seen what happened when I carried his photographs back to the fishing communities where he took them and visited with the descendants of the people in those photographs.

Or what happened when I carried them to local fishing docks, spread them out at fish houses, took them to family reunions and church homecomings and shared them on social media.

In several places, local people kindly hosted gatherings at community centers, local museums, and churches so that we could get together and look at the photographs and talk about them. At those events, we usually shared a supper and then I projected Farrell’s photographs on a screen.

How I wish he could have heard the memories that his photographs awakened, and the stories that spilled forth. How I wish he could have known the joy of it all, as we came face to face with his one true work of art, these portraits of a time and place bound deeply to the sea.

Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.