Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

Currituck County is arguably better known than all of the other Albemarle counties. But it is not known for its 17th century settlers or its roots of American Quakerism like other nearby counties.

Supporter Spotlight

Instead, Currituck County contains a stretch of the Outer Banks, a region of sand and surf visited by over 1 million people each year. But Currituck County’s history is more than beach homes and recreation. It is a county of agriculture, political leadership, and stories of intriguing people who lived on both sides of Currituck Sound.

The best way to understand the history of this unique county is by its two geographic halves. The western half of Currituck County, stretching from North River to Currituck Sound and the Virginia border, was settled around 1650 as part of the Virginian migration to the Albemarle region. According to David Leroy Corbitt, Currituck started out as one of the original precincts of Albemarle County before becoming a county of its own in 1739.

One of the earliest settlers was Thomas Jarvis, who originally lived in Perquimans County near leaders such as George Durant and Nathaniel Batts. Jarvis eventually served on the governor’s council and as deputy governor of North Carolina. Before his death in 1694, Jarvis moved to his plantation on Whites Island in Currituck County, now known as Church Island east of Coinjock.

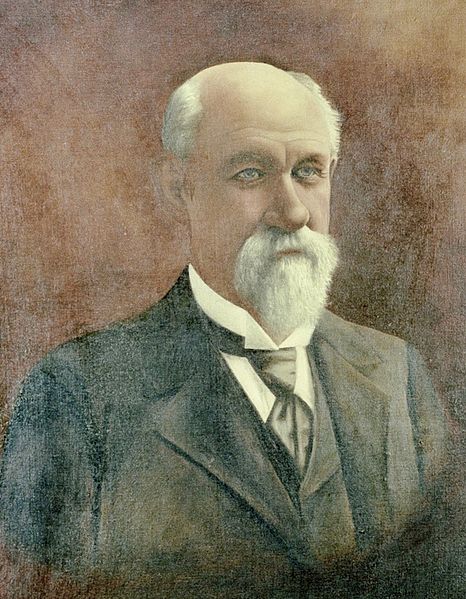

The Jarvis family ended up being one of the most influential in the county’s history. Samuel Jarvis was a longtime political leader in the county who fought in the Revolution according to David Stick. Thomas Jordan Jarvis served as governor of North Carolina and helped to found what later became East Carolina University.

Agriculture has dominated the history and economy of Currituck County’s western half. Early wheat and tobacco culture was supplemented by logging and shingle production from the trees in the county’s swamps. These pursuits, like nearly all agricultural processes in eastern North Carolina at this time, used slaves. According to the Hergesheimer map of 1860, Currituck’s population was 35% enslaved, which was the lowest total in the Albemarle yet higher than 45 other North Carolina counties.

Supporter Spotlight

In transportation, Currituck County benefitted from one of North Carolina’s few antebellum canals. The Albemarle and Chesapeake Canal, completed in 1857 as noted in Alexander Crosby Brown’s book, connected the Albemarle Sound with Norfolk by way of a channel cut through Currituck County at the town of Coinjock. There was also a port in Currituck County for a time, but it was always of negligible size and ceased to function when Currituck Inlet closed up in the 18th century.

Like Camden County to the west, there are no incorporated towns in Currituck County. The largest communities in the western half are Moyock, Grandy, and Coinjock. Currituck is a small community on Currituck Sound that contains the historic jail and the 19th century courthouse, a sizable brick structure described by Ruth Little-Stokes as having notable neoclassical details.

One of North Carolina’s few remaining Rosenwald schools, which are schools built for African Americans in the early 20th century, is currently being restored nearby. Currituck also contains a ferry to Knotts Island, a historic island in Currituck Sound that contains a wildlife refuge and a vineyard.

The eastern half of Currituck County has a much different history dominated by tourism and the shifting nature of the Outer Banks. Known as Currituck Banks, this section used to be an island until Currituck Inlet at the northern edge closed up in the 19th century. Until the formation of Dare County in 1870, Currituck County’s eastern section originally stretched down to the area of present-day Kitty Hawk; the current border, a line north of Duck, used to be the now-filled Caffey’s Inlet.

The first European to visit the area may have been Giovanni De Verazzano, who explored parts of the Outer Banks in 1524. Early settlers were few and far between. William Byrd discussed two of them in a tale relayed by David Stick in his “History of the Outer Banks.” The residents described by Byrd were hermits who lived in a hut, “subsisted chiefly upon Oysters,” and wore no clothing except for their beards and hair.

In the mid-19th century, Currituck Banks began to attract wealthy visitors. Motivated by stories of massive flocks of geese, the first shooting club opened in the area in 1874. It was followed in 1922 by the Whalehead Club, an ornate lodge occupying 35 acres of what was then undisturbed marsh.

One of North Carolina’s famed lighthouses, the Currituck Beach Light, was built in 1875 in the community of Corolla. It is tied for the second-tallest lighthouse in North Carolina with the Bodie Island Light and can be climbed several months out of the year.

By the 1920s, eastern Currituck County started to open up to tourists from across the country. Tourism was facilitated by the Good Roads Movement and a number of essential bridges, most notably the Baum Bridge in 1928 and the Wright Memorial Bridge in 1930. Visitors enjoyed the white sand beaches, hunting grounds, and the wild horses in Corolla.

Eventually, Carova Beach became a secluded tourist destination. It is notable for being only accessible by boat or by driving on the beach. As Kip Tabb wrote in a 2017 article on development at the beach, “Although traffic has been increasing, the lack of infrastructure and paved roads has kept visitation modest by comparison to other parts of the Outer Banks.”

The differences between eastern and western Currituck County are stark. Eastern Currituck County’s population swells in the summer months to about 50,000 people, more than double the year-round population of the entire county. Tourists are limited in the western half while comprising nearly the entire economy of the eastern half.

The vacationers and tourists on Currituck Banks include some of the wealthiest and most powerful people in the world. Former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia owned a house in Corolla, and Bill Gates was rumored in 2021 to have once rented one. In contrast, western Currituck County, which is the home of the majority of Currituck’s 1,377 African Americans, is rural, isolated and mostly free from celebrity sightings.

These disparate situations between the two halves will only continue to grow. The western half will likely be bolstered by the mid-Currituck bridge and the growth of Elizabeth City and Hampton Roads. This section of Currituck County may become either a stop on the way to the Outer Banks or a distant bedroom community for Chesapeake and Suffolk, Virginia.

The eastern half, on the other hand, will continue to attract tourists but is cut off from Virginia by False Cape State Park, which does not allow vehicular access from North Carolina. These differing paths and experiences give Currituck County its character and make it one of the most remarkable counties in all of North Carolina.