Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

In an area defined by small towns and miles of contiguous farmland, Pasquotank County is by far the most developed county in the Albemarle Region.

Supporter Spotlight

Its county seat, Elizabeth City, is home to restaurants, shopping and the kinds of big-box stores that are ubiquitous in cities like Greenville or Rocky Mount. But Elizabeth City was not always the center of the region or even the center of Pasquotank County. It took many decades, civil unrest and a citywide rebuilding to make Elizabeth City and Pasquotank County the regional anchor that they are today.

Pasquotank County was an original county of the Albemarle region. According to historian David Leroy Corbitt, the county began as Pasquotank Precinct of Albemarle County in 1668. Its original boundaries were the Virginia border to the north, Albemarle Sound to the south, the North River to the east, and Little River to the west. The northeast section of Pasquotank County became Camden County in 1777. Early settlers, including Nathaniel Batts and George Durant, purchased land from Native Americans and started moving in within a decade of the precinct’s formation. Pasquotank became its own county in 1739. The first town was not Elizabeth City but Nixonton, which was established in 1758 on the Little River.

Pasquotank County was in many ways the political center of the Colony. The first assembly in the Colony was known as the Grand Assembly and met in Pasquotank County in 1665. This and other early meetings set up the Colonial government, which centered around the governor and his council along with an assembly of elected representatives.

The first governor of North Carolina, William Drummond, served the Colony from Pasquotank. According to author and Pasquotank native Bland Simpson, Drummond was a decent governor whose power was undermined by Virginia’s William Berkeley. After his term in office, Drummond moved to Virginia, became a follower of Nathaniel Bacon against Berkeley, and was executed when Bacon’s Rebellion failed in 1677.

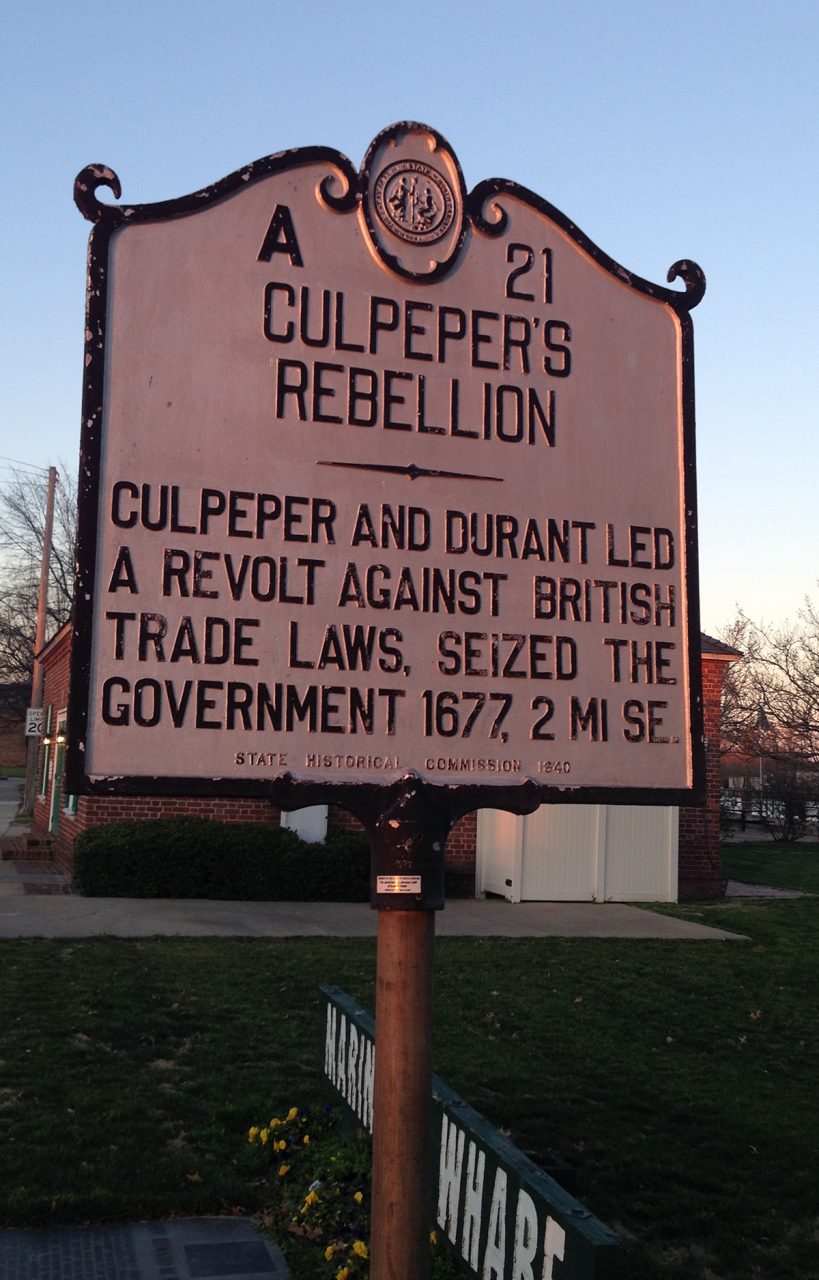

Shortly after Drummond left office, the people of Pasquotank rose up to evict another questionable governor. Culpeper’s Rebellion occurred when Gov. Thomas Miller arrested popular local citizen George Durant for opposing a new law meant to enforce customs duties. In his history of the rebellion, Hugh F. Rankin noted that its spark was a set of remonstrances written by John Culpeper in which he accused Miller of numerous crimes in the name of the “Pasquatanckians.” A local mob broke Durant out of jail and filled the jail instead with the governor and several of his deputies. North Carolina went several years without an accepted governor before the Lords Proprietor, then owners of the Colony, sent one to the Colonists’ liking.

Supporter Spotlight

During the time of Culpeper’s Rebellion, Colonial life was simple. Most settlers were farmers or traders. They grew corn, wheat and tobacco. Some were Quakers converted during the earlier visit by George Fox and William Edmundson, but most were Anglicans who did not regularly attend church services. The wealthiest citizens mingled often with the poorest and lived in modest brick houses. As Hugh F. Rankin wrote of the 17th century Albemarle region, “The business of hacking a home out of the wilderness was far too difficult to permit the delicacies of elegant living.” The most exciting regular occurrence was court, where citizens met to drink, socialize, and air their grievances large and small.

No buildings survive in Pasquotank County from this early period of the Colony. But one house, the Old Brick House in Elizabeth City, remains from the 1750s. It was built by Robert Murden, a local militia and assembly member. The house, rare for its twin brick chimneys and considerable size, has an elegantly designed interior and an elaborate carved mantel. H.G. Jones noted that because of their lavish interiors, the Old Brick House and Edenton’s Cupola House “were likely considered mansions in comparison to standard residences of the region.”

The late Colonial period was one of stagnation for much of Pasquotank County. As the 1700s progressed, the population center of the Colony shifted, first to Edenton and then to the Neuse and Cape Fear River regions. But Pasquotank gained renewed relevance in the 1790s with the founding of Elizabeth City at the narrows of the Pasquotank River. Likely named after either a local tavern keeper or a county in Virginia, Elizabeth City soon became a prosperous port. It was located a few miles from the Great Dismal Swamp Canal, which was completed in 1805 and greatly facilitated water transportation between North Carolina and Virginia.

Elizabeth City finally surpassed Edenton by 1880 to become the largest town in the Albemarle region. Elizabeth City also had one of the largest free African American populations in the state. According to John Hope Franklin, Pasquotank County had more than 900 free African Americans in 1830, many of whom came across the Virginia border and lived in Elizabeth City.

The Civil War devastated Elizabeth City. Parts of the city were burned in 1862 and rebuilt over the next few decades. This rebuilding included the present-day Neoclassical courthouse, constructed on East Main Street in 1881 and 1882. The end of slavery enabled Pasquotank County to find new sources of economic prosperity. Agriculture continued to be prominent, but there was a renewed focus on industry. By the 1880s, there was a wide variety of businesses such as a cotton mill, grist mills, and a soda bottling establishment. Some of these buildings, in addition to an iron works dating from the 1890s, survive.

Elizabeth City also embraced higher education. Elizabeth City State University was founded in 1891 as the State Colored Normal School at Elizabeth City. It solely trained African American teachers at first but later expanded its scope. The university is now the only school in North Carolina that offers a four-year degree in aviation science. Alumni include athletes such as American Basketball Association star Mike Gale and NFL standout Everett McIver, a Dallas Cowboy who was once famously stabbed with a pair of scissors by Hall of Famer Michael Irvin. A more recent graduate, Omari Salisbury, became nationally known in 2020 for his role as videographer for social justice movements, for which he received a profile in the Seattle Times.

The College of the Albemarle, which opened in 1960 and is now located 3 miles north of Elizabeth City State University, is the other major institution of higher education in Pasquotank County. It currently serves as the primary community college for the Albemarle region and boasts one of the state’s largest health care programs, according to EdNC.

Today, Elizabeth City remains the economic center of Pasquotank County. The other communities in the county are comparatively small. Weeksville is unincorporated and long ago lost its claim to fame: a lighter-than-air airship hangar once operated by the Navy and private companies. Nixonton also remains as an unincorporated community, having lost its town status long ago according to the North Carolina Gazetteer. Most of the county still subsists on agriculture. Large fields of corn and soybeans stretch along U.S. 17. Even though Pasquotank is the 89th largest county in the state by area, it is seventh in the state in corn production according to official statistics.

But even Elizabeth City may not be the main determinant of Pasquotank County’s trajectory over the next few decades. The Hampton Roads region of Virginia continues to encroach into North Carolina. Elizabeth City is only 47 miles from Norfolk and is already part of the same metropolitan area as defined by the Census. It remains to be seen whether Elizabeth City will continue its centuries-long tradition of centrality to the Albemarle region or if it will be another outpost for the growing urban sprawl of southeast Virginia.