Guest commentary

For nearly a century, military personnel have been victims of toxic exposure to a wide range of toxic agents, oftentimes without them even knowing.

Doing a deep dive into the history of this issue only highlights a bitter irony: Veterans who have been trained and prepared to bravely fight and face the horrors of war are now suffering or being killed by a silent and slow enemy — toxic exposure. Moreover, their suffering often feels invalidated by the crushing bureaucratic process that is claiming Veterans Affairs benefits related to this issue.

Supporter Spotlight

Although toxic exposure in the military has been extensively discussed throughout the years and is a known issue, when it comes to connecting the dots between their disease and military service, many veterans and their families still have significant gaps, especially if they haven’t been deployed. This is exactly why it is critical not only to continue discussing, researching and informing about this issue but also to have a system in place that first and foremost acknowledges the full spectrum of side effects to toxic exposure and the existing link to veterans’ military service, facilitating their access to benefits.

Extent of exposure

Regardless of rank or role in the military, many service members have been exposed to toxic agents such as asbestos, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, agent orange, and many others that have been used throughout history and have contaminated military sites, locations, and grounds. The truth is that almost all veterans have been exposed to hazardous or toxic products at some point during their service, whether it was during training, work duties, or on the base. Many of these agents have been linked to cancer and noncancerous illnesses.

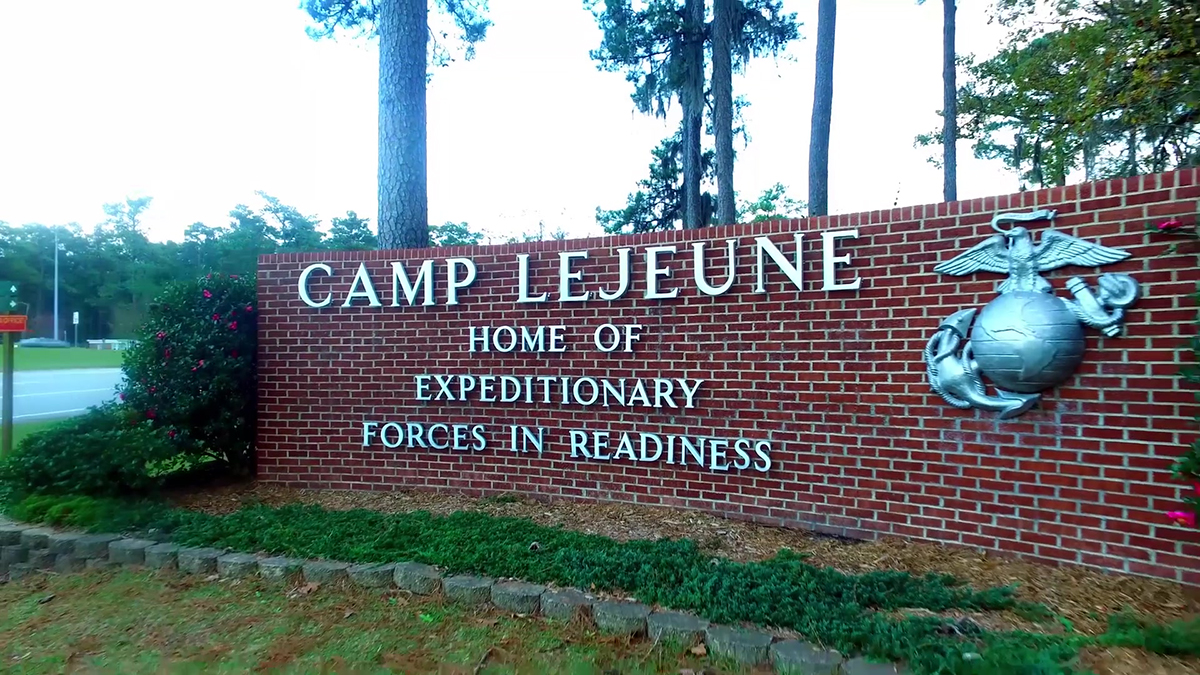

While the focus now in the media might be on the issue of toxic exposure related to burn pits in Afghanistan and Iraq, and rightfully so, it is extremely important to keep shining the light on the others as well. And unfortunately, there are many identified toxic agents and, worse still, full-blown hazardous disasters that have plagued military service ever since World War I with the rise and popularity of asbestos. But perhaps the worst one that needs more acknowledging is the disaster that was Camp Lejeune.

In the early 1980s, tetrachloroethylene (PCE), trichloroethylene (TCE), dichloroethylene (DCE), benzene, and vinyl chloride were discovered in two water-supply systems on the Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. These water treatment plants supplied the water systems that served enlisted-family housing, unmarried service personnel barracks, base administrative offices, schools, and recreational areas. They also supplied water to the base hospital and an industrial area. However, officials did not close the contaminated wells until 1985, when they finally informed Marine families that chemicals had been detected in the water. According to health officials, up to 1 million people may have been exposed to water toxins for up to 30 years before the wells were closed.

Because the chemicals used at Camp Lejeune are extremely toxic to humans, those who were exposed are now at a high risk of developing a serious, even fatal disease as a result of their exposure. Some of the most common diseases associated with the exposure at Camp Lejeune are bladder cancer, breast cancer, kidney and lung cancer, leukemia and reproductive health problems.

Supporter Spotlight

Although Camp Lejeune is widely regarded as one of the worst cases of water contamination in U.S. history, it is far from the only toxic military site. The Environmental Protection Agency currently has 128 military installations on its list of Superfund sites, which are areas so contaminated with hazardous substances that the federal government has designated them as National Priorities List sites for cleanup.

But that’s not all. When speaking of contaminated sites, one must mention the thousands of PFAS contaminated sites.PFAS are a group of toxic fluorinated chemicals whose primary source is aqueous film-forming foam, also known as AFFF. For years, PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals,” have contaminated thousands of sites in the United States, including military bases where thousands of service members and their families live and work. Because of their nature, efforts to clean up contaminated sites are slow and will most likely continue for quite some time, as there are approximately 2,854 locations in 50 states that are still known to be contaminated as of August.

Exposure to toxic agents, be it asbestos, PFAS or contaminated water can lead to very serious health consequences that many veterans are struggling with today. In many cases, those health consequences are cancers that slowly develop over a long period of time and that oftentimes are either misdiagnosed or discovered in terminal phases. It is truly a tragedy that so many veterans have to battle today with these diseases after years of service and, as if that’s not enough they also have to battle for their rights.

Problematic approach

While it’s true that there are ongoing efforts to clean up the contaminated sites and the VA does acknowledge the link between toxic exposure and some diseases (some being the key word here), what’s being done is not nearly enough.

One of the veterans I work with has recently stated that:

”Starting the process for accessing VA benefits feels like jumping through hoops. Sometimes even like a slap in the face, especially trying to prove a link between my disease and the publicly known contaminated base I was on. There is too much bureaucracy that gets too complicated that it just makes you wonder if you’re fighting for nothing. But in the end, all you can do is ask for some help and hope for the best.”

Hope indeed. In lack of clearer, more broad and efficient legislation, all veterans can do is hope that their benefits will get approved. And here is exactly what is problematic about it. Veterans shouldn’t “hope for the best” after completing their service and being diagnosed with a severe or terminal disease. They should be automatically protected, helped and have their diseases validated by the responsible authorities. By this point there is sufficient research on the effects of toxic exposure and more than enough evidence to its extent at military installations throughout history. So why are things moving so slowly? Why is it so complicated? Why is toxic exposure still treated as if it is a light issue in terms of urgency, although the reality shows just how serious it is and even declaratively, lawmakers acknowledge it?

A law passed in 2012 provides veterans and family members who lived on the base with health care coverage for 15 conditions. Veterans may also be eligible for disability benefits for eight conditions that are thought to be related to the contamination. As part of the Caring for Camp Lejeune Families Act of 2012, qualifying veterans can receive VA health care (except dental care) if they served on active duty at Camp Lejeune for at least 30 cumulative days between Aug. 1, 1953, and Dec. 31, 1987.

There is some hope for veterans suffering as a result of toxic exposure at military bases with the traction that the Toxic Exposure in the American Military Act, or “TEAM” Act has recently gained. The TEAM Act was also proposed in Congress last year, but it failed to gain traction.

This is a bipartisan bill that would expand access to VA care and benefits for veterans who were exposed to toxic substances while serving, create a consistent process for determining presumptions of service connection for illnesses, create an independent scientific commission, and authorize additional research to determine whether conditions are linked to toxic exposure.

The TEAM Act would benefit not only veterans who served at Camp Lejeune, but also those who have been exposed to burn pits and other toxic substances. Now, Congress must act to ensure that military servicemembers and veterans who have been harmed by toxic exposure as a result of their military service receive the medical care and benefits they are entitled to. Unfortunately, to date, there doesn’t seem to be much urgency or significant movement in regards to this bill.

Earlier this year the Comprehensive and Overdue Support for Troops of War Act of 2021, also known as the COST of War Act, was introduced as part of a larger effort to assist veterans who have been exposed to toxic substances. If passed, this would automatically grant 3.5 million veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars access to VA health care. They would also, among other things, reform VA’s current process for handling toxic exposure claims and add new conditions to the presumptive list for toxic exposure. However, again, not much progress seems to have been made until now.

The lack of urgency to pass these bills and to reform the VA’s process for handling toxic exposure claims is problematic to say the least and should become a priority. The fact that after 100 years of proven toxic exposure in the military veterans still have to fight for their rights is a travesty. We need to do better, as a nation, for our veterans.

To stimulate discussion and debate, Coastal Review welcomes differing viewpoints on topical coastal issues. See our guidelines for submitting guest columns. The opinions expressed by the authors are not necessarily those of Coastal Review or the North Carolina Coastal Federation.