This is part of a series of special reports by Catherine Kozak, who attended the COP26 climate conference held in November.

GLASGOW, Scotland — Until this year, methane hadn’t received the attention it deserved for being a huge source of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, despite being nearly as much to blame as carbon for overheating the planet.

Supporter Spotlight

Last month when the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Scotland elevated awareness of its danger to the global stage, the world was left wondering what to do about methane emitted not just from gas pipes, but also from landfills, food waste, agricultural operations and livestock.

“We’ve been working on methane for over a decade,” Fred Krupp, president of the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, said in an interview at the “Methane Moment” pavilion at the climate summit, also known as COP26, shorthand for the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties, nearly 200 nations that agreed to a climate pact in 1992. “This is the first time the issue has become prominent.”

Still, he said that the total amount of methane released in the atmosphere is only an estimate because of the difficulty not only capturing it, but measuring it. For instance, most of livestock-generated methane, a major global contributor, is dispersed from the mouths and intestines of cattle, not their manure, presenting an obvious challenge. But recent technological advances, he said, are now making it possible to precisely measure the gas detected in the air, and technology to enable its use as fuel in some conditions has become more affordable.

“Methane from the animals is basically the same as natural gas — biogas,” he said. “You can feed it into a pipeline, but it can also produce electricity on site.”

On Nov. 2, the Biden administration pledged numerous measures to address climate change impacts, including incentive-based approaches to reducing methane emissions with alternative manure management systems and expansion of on-farm generation and use of alternative energy. The U.S. and European Union had earlier announced a 90-nation pact to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030 from 2020 levels.

Supporter Spotlight

If methane emissions are stopped, there quickly would be positive results.

“Dollar for dollar,” Krupp said, “this is the most effective way to bring temperatures down.”

But it won’t be easy.

In North Carolina alone, mitigating a significant source of methane emissions — hog farms — by installation of biogas technology involves diving into longstanding social and environmental justice issues, multiple legal challenges, controversial permitting and accusations of broken agreements and lopsided financial benefits.

Hog waste from thousands of swine operations in the state is flushed from barns into what are essentially dirt pits, most of them unlined and uncovered. After sitting and “digesting” for a while, the slurry is sprayed onto nearby cropland. Depending on wind direction or whims of the sprayer, residents have complained that the residue has all too frequently coated their homes and filled the air they breathe with retched smells and toxic fumes that burn their eyes and create multiple health problems.

Municipal solid waste landfills are the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the United States, about 15.1% of total emissions in 2019, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Climate scientists say that although methane accounts for about 10% of human-caused greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, it accounts for 30% of climate change impacts. The gas has a disproportionate destructive effect: a ton of methane in the atmosphere creates about 80 times more warming than a ton of carbon dioxide emissions. But it doesn’t stick around as long as carbon.

“Methane dissipates,” Michelle Nowlin, co-director or the Environmental Law and Policy Clinic at Duke University School of Law, explained in a recent interview. “I think it’s like on a 20-year timescale, whereas carbon dioxide may take a 100-year timescale, but the power that it packs in that 20 years is significantly greater than what the carbon does over that longer timeframe. So it’s a much shorter term, much more intense contribution to global warming than the carbon dioxide itself.”

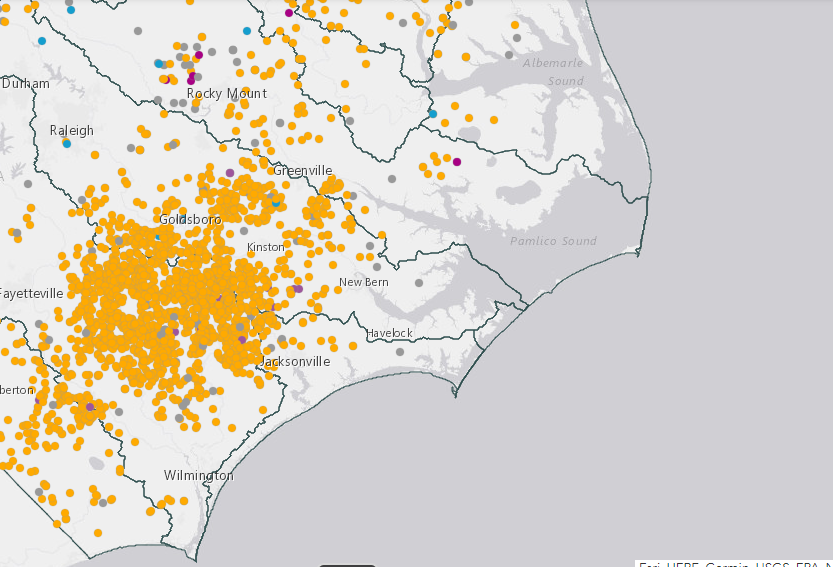

North Carolina has no fracking facilities, and limited natural gas pipeline infrastructure, but the waste from millions of pigs emits enormous amounts of methane — and it’s a lot more complicated to measure and capture than what leaks from a pipe.

The 2,300 or so swine concentrated animal feeding operations operating in North Carolina today are a big reason that the state is a “leading contributor” of methane emissions in the country, Nowlin said. In addition, the state’s industrial animal operations also include large numbers of turkey and chicken farms.

Nowlin, who has worked on numerous hog waste management issues for close to 25 years, co-authored with Emily Spiegel a chapter in a research book published in 2017 on climate change and agricultural law, wrote that about 30% of agriculture’s total contribution to greenhouse gases is from the livestock sector.

“Despite the significant role the livestock industry plays in greenhouse gas emissions, it has thus far evaded regulation in the US,” the authors wrote. “Instead, approaches to reducing livestock greenhouse gas emissions have been voluntary, incentive-based, and wholly inadequate to the scale and urgency of the problem.

“As we seek ways to lower greenhouse gas emissions and forestall the effects of global climate change, we must remove the protections long afforded the agricultural industry and adapt existing regulatory tools to address its contributions,” they wrote.

Dominion Energy and Smithfield Foods Inc. are currently proposing to build what they call “North Carolina’s largest renewable natural gas project” through their joint venture, Align Renewable Natural Gas.

Planned in Duplin and Sampson counties, the project would generate enough energy to power more than 3,500 homes, according to an August 2019 press release on Smithfield’s website. The technology involves covering the lagoons to trap methane that is then processed and converted to biogas, which is injected into existing natural gas distribution pipes. The company is also proposing to create biogas from its hog slaughterhouse in Bladen County.

Swine waste-to-energy techniques have gained support from proponents who say they address the environmental concern with methane emissions while creating an additional revenue stream and saving and/or creating jobs.

But Derb Carter, director of the Southern Environmental Law Center’s North Carolina office, which among other legal actions has challenged permits that the state Department of Environmental Quality issued for the project, said that capping the lagoons would increase the amount of harmful nutrients in the liquified waste, and have an even worse impact on water quality.

“Numerous studies have tied the lagoon and spray-field system to increased nutrient levels that plague our coastal waters, leading to periodic algal blooms and fish kills,” Carter wrote in a December 2020 editorial, adding that Smithfield has for two decades declined to install environmentally superior systems, despite an agreement with the state attorney general to do so.

“As Smithfield has requested,” he wrote, “the state can allow Smithfield to simply cover lagoons, capture and profit from biogas, and perpetuate the flawed lagoon and sprayfield system.”

For residents along coastal North Carolina, the hog lagoons and their methane emissions may seem like a distant concern. For those that remember Hurricane Floyd in 1999, when floodwaters inundated the open pits and drowned thousands of hogs and sent the pig filth and tons of putrid sediment and floating carcasses toward the sounds and ocean in a pink-purple swath of polluted water, the concern may seem valid.

“Because even though they’re not right there on the coast, a large number of those operations are present in the coastal counties and that coastal plain,” Nowlin said. “And of course, to the extent that it’s deposited on the lands and waters of eastern North Carolina along the coast, and at the coast’s back door, and all the waste that runs off into those waters gets carried to the coast and to the sounds.

“That’s why we have nutrient pollution in the Albemarle-Pamlico sounds,” she added. “So it’s a significant issue for people on the coast, even if they don’t recognize it being so because it’s not right in their backyard.”

Methane is just one of the pollutants from hog lagoons, and biogas production — so far — offers an imperfect and inadequate solution.

As far as global warming, Nowlin said that ammonia, another byproduct of hog waste, is also a problem because when that ammonia is emitted into the atmosphere it combines with nitrogen gas and oxygen to create nitrous oxide, which is an even more potent greenhouse gas.

According to a 2020 study “Reconciling Environmental Justice with Climate Change Mitigation: A Case Study of NC Swine CAFOs,” co-authored by Ryke Longest, clinical professor of law, Duke Law School, and co-director of the Duke Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, and D. Lee Miller, lecturing fellow of law at Duke Law School, the “confinement, consolidation and concentration” of hogs in the concentrated animal feeding operations, which are located in 10 counties in the coastal plain, has caused a multitude of negative impacts to the environment and the health of nearby communities.

The state’s hog industry is one of the largest in the United States, and according to the report, the swine slaughter facility in Tar Heel, in Bladen County, is the world’s largest. To illustrate the dramatic change the industry has made in the state, the authors said that there were about 11,000 small swine farms throughout North Carolina in 1982. Between 1989 and 1995, they said, 700 CAFOs housing as many as 8.2 million hogs were built, and 7,000 small hog farms went out of business.

“The new mega-facilities are concentrated in a handful of socially and environmentally vulnerable communities in the Coastal Plain where the most prominent geological features are sandy soils, high water tables, and proximity to the coast,” the report said.

The CAFOs, the Duke researchers say, have created pollution and diminished the quality of life of communities. Lagoons break down the contents of the waste and turn it into polluting gases, and the liquid waste seeps into groundwater and runs off into waterways.

“Now, as global concern over climate change drives corporate demand to decarbonize supply chains, market forces exert pressure for converting existing lagoon and spray field CAFOs into biogas factories,” Longest and Miller wrote. “Biogas mitigates greenhouse gas emissions by combusting methane into CO2 while generating revenue from electricity sales and carbon offset credits.

“Reconciling the interests of environmental justice, local natural resources, and the global climate requires agribusiness to reinvest some of this financial boon into the clean technologies they have promised — and shirked — for decades.”

Next in the series: A coastal North Carolina farmer’s perspective.