Part of a history series examining each of North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties.

The Albemarle region is known for its historical legacy, beautiful natural areas and quaint architecture. It is also mostly a quiet, rural area with small towns and limited economic activity.

Supporter Spotlight

The quietest, most rural county in the region by far is Camden County. It is known not for its buildings or major historic events but for its canal and its swamp.

While it does not have the tourist sites of Edenton or the industry of Elizabeth City, Camden County is still a fascinating part of North Carolina’s oldest region.

Camden County was part of the Albemarle, the first area permanently settled by the English in North Carolina. Its earliest settlers came south from Virginia and purchased land from the Yeopim Native Americans.

The county was originally the eastern part of Pasquotank County. The state legislature formed Camden County in 1777 because of the “width of Pasquotank River, and the Difficulty of passing the same, especially in boisterous weather,” which prevented some residents from reaching the courthouse easily.

As noted by David Leroy Corbitt, Camden County’s general boundaries were the Pasquotank River to the west, the North River to the east, and the Virginia border.

Supporter Spotlight

One sizable house still remains from this early period, Milford, near the county seat of Camden. Milford was constructed in 1746 by John Ivey, a local planter mentioned in William Byrd’s “History of the Dividing Line.” It is one of the largest pre-1750 houses in the state, made of brick with two stories. Milford is known for its rare, gable design pattern, which, according to H.G. Jones, was only found in one other colonial house in the South.

Like the Old Brick House in Elizabeth City and the Cupola House in Edenton, Milford was definitely a mansion during its day. The vast majority of colonists in Camden County lived in much simpler dwellings, at first log cabins and then one-story plank houses.

Camden County’s economy has always been defined by the Great Dismal Swamp, which makes up its upper half. The swamp is one of the largest on the eastern seaboard, comprising more than 100,000 acres in North Carolina and Virginia.

Byrd’s expedition was one of the first European groups to encounter and cross the swamp. Byrd wrote that the swamp did not contain most of the fanciful creatures that locals told stories about, but that it “had one Beauty, however, that delighted the Eye, tho’ at the Expense of all the other Senses: the Moisture of the Soil preserves a continual Verdure, and makes every Plant an Evergreen, but at the same time the foul Damps ascend without ceasing, corrupt the Air, and render it unfit for Respiration.”

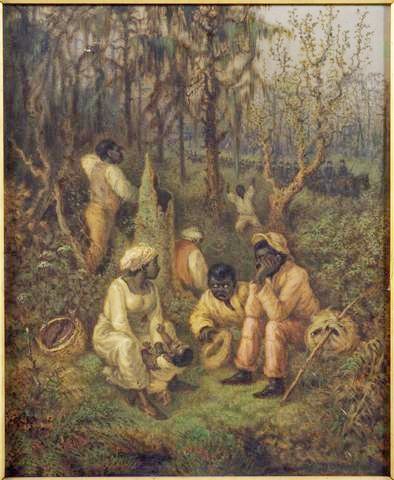

As its edges were settled in the 18th and 19th centuries, the swamp became a source of shingle production. It was also a home for runaway enslaved people from North Carolina and Virginia.

They formed self-sufficient maroon communities, sometimes interacting with whites near the canals and edges of the swamp and often staying entirely away from white society.

Recent scholarship has unearthed several of their communities and has started to understand the extent of African American settlement in the region, according to a 2016 Smithsonian Magazine profile.

The early 19th century was a prosperous period for Camden County. It was the site of the Port of Camden up to the 1820s. By 1860, the county’s enslaved population was 42% of its total population, the 27th highest total in the state according to the Hergesheimer map. Many of these slaves worked in shingle production or on small farms growing foodstuffs such as corn and wheat, an 1860 census document states.

The Great Dismal Swamp Canal, which opened in 1805 and was widened in 1829 with the use of slave labor, passed through the county. The canal connected the Albemarle region with Norfolk and the Chesapeake Bay.

One of the few sizable communities in Camden County grew up along the canal.

South Mills was formed in the 1830s and named after mills that used water from a canal spillway for power. It was the site of a Civil War battle in 1862, where Confederates prevented a Union attempt to destroy the Great Dismal Swamp Canal’s locks, a 2012 Virginian-Pilot article explains.

The only other community with any size in Camden County is the county seat of Camden. Established as Jonesborough in 1792 according to the North Carolina Gazetteer, it is located on the Pasquotank River.

Two early public buildings remain in Camden from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Camden County Courthouse is an 1847 Greek Revival structure with four columns and a sizable porch. There is also the Camden County Jail, a brick building completed in 1910 that now houses offices and a museum.

Camden County remained one of the smallest and most lightly populated counties in North Carolina throughout the 19th and 20th century. In 1900, its population was only 5,474, a paltry total that made it less populated than 16 of the state’s towns. But a number of remarkable individuals still hailed from the swampy northeast county, many of whom were African American.

Julian Williams escaped from slavery to fight in the Union Army during the Civil War, while Moses Grandy purchased his freedom in the 1820s, wrote a narrative of his life, and later became an influential abolitionist.

Later on, Mary Elliott Hill, 1907-1969, born in South Mills, became a notable chemist who published dozens of papers and formulated processes important in plastic production.

Today, Camden County remains one of the most rural, sparsely populated counties in the state. It has the fifth smallest population in the state and still no incorporated towns.

But these circumstances may change in the next decade or so. Elizabeth City continues to grow on Camden County’s western border. There is a chance that its growth will jump the Pasquotank River and turn Camden into a bedroom community.

In addition, a new highway-widening project of US 17 and the proposed mid-Currituck bridge could bring thousands of travelers every year through Camden County on their way to the Outer Banks.

Time will tell if Camden County will become a waypoint for tourists or if it will retain the rural character that has defined it for the past three centuries.