Sören Funk

Microplastics are everywhere.

“It’s in our water, it’s in the ocean, it’s in the animals, in the air, even in space,” Ana Zivanovic-Nenadovic, North Carolina Coastal Federation assistant director of policy, said recently during a virtual forum on microplastics.

Supporter Spotlight

Since the mass production of plastics began in the mid-20th century, plastic has permeated our lives, she explained July 15 to the 202 from 29 different counties logged on for the North Carolina Coastal Microplastics Forum, organized by the federation.

The online forum included presentations from researchers, educators and environmental group representatives who explained the different types of microplastic pollution, the risks microplastics pose to the natural environment and human health, and current policies.

“This forum is the first step in our effort to inform the public and galvanize support for the change that will hopefully lead to solutions to microplastics,” Zivanovic-Nenadovic said.

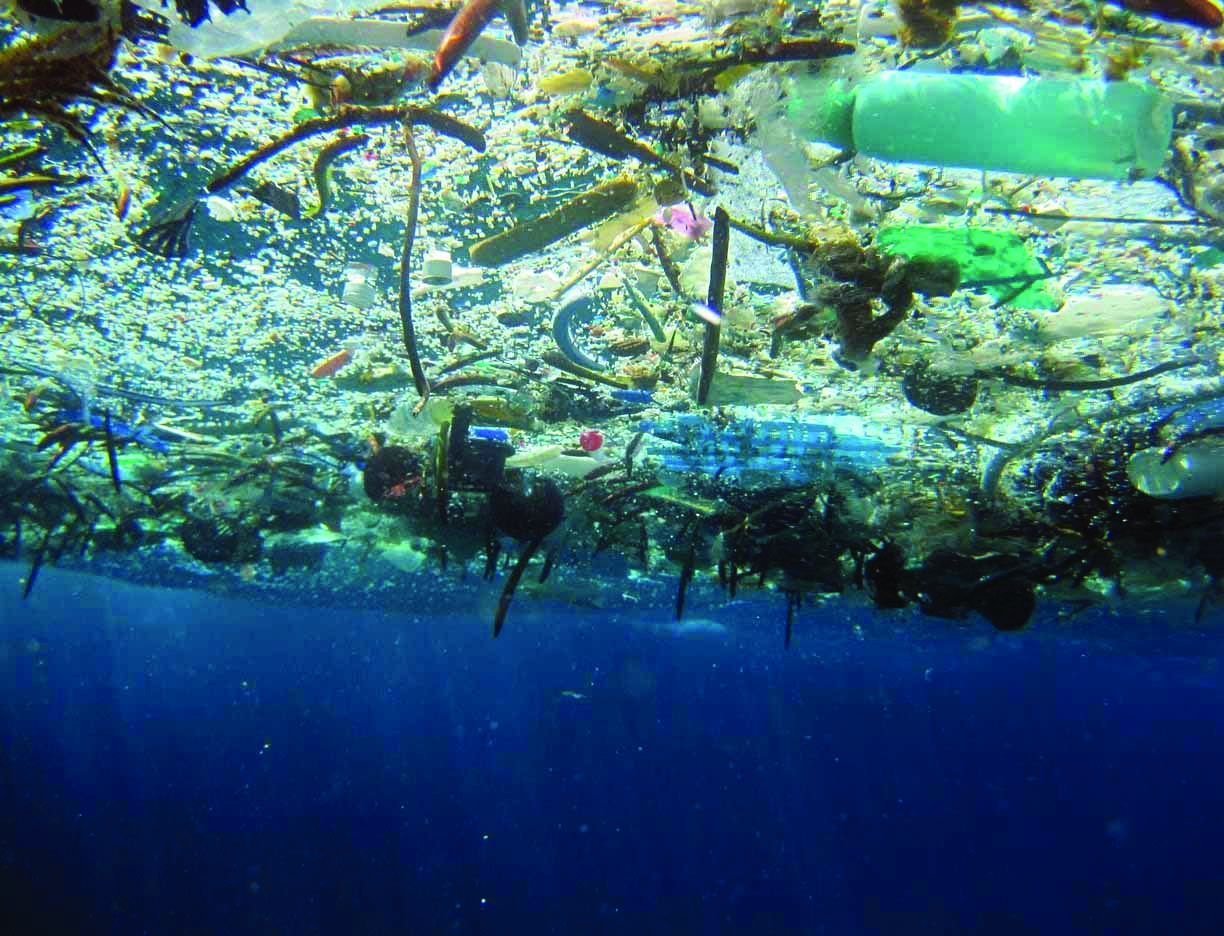

Bonnie Monteleone, executive director of the nonprofit Plastic Ocean Project Inc. and a plastic marine researcher, said she found in her research that around 3.86 metric tons of microplastics, or pieces measuring less than 5 millimeters, are in the North Atlantic.

The ocean is turning into “plastic soup,” Monteleone said.

Supporter Spotlight

Plastic is the newest member of the food web “because plastics break up, not down. They’re breaking up into smaller and smaller particles, making them more bioavailable for all the organisms in the ocean. So I like to call it the ‘big small problem’,” she said. “As the particles get smaller, we start to see less and less of them and scientists are really concerned to where these smaller particles are going.”

One place these microplastics are being found is in our seafood.

Dr. Susanne Brander, a member of the faculty at Oregon State University since 2017 and previously faculty at University of North Carolina Wilmington, explained that microplastics are transferred through food webs and then are ingested directly by organisms, “but they are also trophically transferred, meaning that they are ingested by smaller organisms that are then fed upon as prey items by forage fish or larger predators. The ultimate result is that these items can end up in seafood on our dinner plates.”

According to an analysis, globally, about 26% of a fish species are found to ingest microplastics, which is roughly the same in the U.S. Microplastics affect the fish’s ability to survive and to reproduce, and that can have population level impacts.

“So we should think about this from a human health perspective but also from a fish health perspective. And in the end, that’s going to influence how many fish there are out there to catch.”

Dr. Marielis Zambrano with North Carolina State University department of forest biomaterials said that these microplastics being found in the ocean — and in our seafood — are from synthetic textiles, tires, city dust, road markings, marine coatings, personal care products and plastic pellets, or nurdles.

Microplastics are synthetic solid particles that don’t dissolve in water and are less than 5 mm in size. It’s estimated that a minimum of 5.25 trillion plastic particles weighing 270,000 tons are floating in the world’s oceans, she explained.

The average person ingests more than 5,800 particles a year of synthetic debris, found in everything including seafood, beer, tap water and sea salt. Microplastics are even found in human stool samples, meaning we are eating microplastics, Zambrano said.

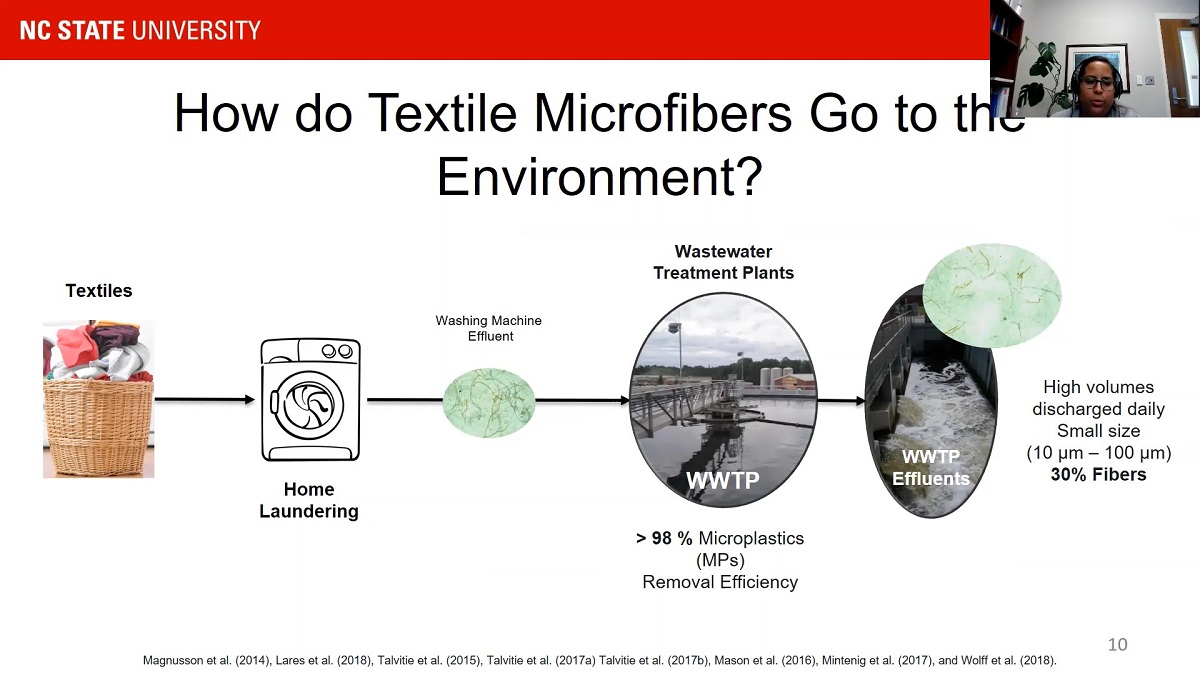

Found in 99.7% of all samples taken from the ocean surface, microfibers are a primary source of microplastics. These microfibers get into the environment through the home laundry process. The effluent is processed in wastewater treatment plants but some of the particles are too small to filter out before being discharged. Microfibers are also in the air from carpet, clothing and other materials.

Dr. Richard Venditti, the Elis-Signe Olsson professor in Paper Science and Engineering in the Forest Biomaterials Department at N.C. State University, said a study at the university found that cotton and rayon, both based on natural materials, degrade in about 35 days in lake water in a simulation.

“In stark contracts, polyester and many other plastics are completely inert to biological activity and persist in the lake water for a very long time,” which is a challenge, he said.

The microfiber problem has no unique solution but there are some possible ways to help, such as filters on washing machines, a sustainable coating on fabrics, using natural or plant-based fibers, or new methods to spin fibers that are durable, though all of these are not without problems.

Haw Riverkeeper Emily Sutton reiterated that microplastics are a huge public health concern and noted the high percentage of microfibers they find while testing because wastewater treatment plants aren’t able to remove all those before being discharged. Haw River, a tributary of Cape Fear River, is in the central part of the state.

Plastic, which is getting into our bodies through drinking water, has even been found in breast milk, she added. There’s also concern about the chemical compounds these plastics are made of, as well as about PFAS and other chemicals. “Those compounds are also being soaked up by these plastic particles” that are making it into our bodies.

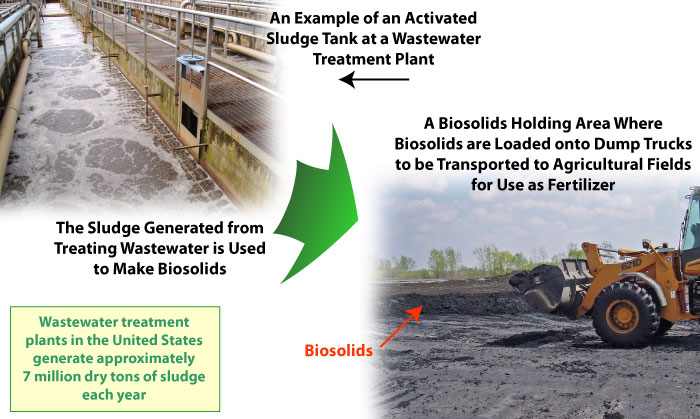

Dr. Scott Coffin, a research scientist at the California State Water Resources Control Board, said that while wastewater treatment plants are effective at removing microplastics — between 88 and 99% of plastics — what is removed is then turned into sludge.

The sludge, which contains a high level of nutrients, is often transformed into biosolids and used as fertilizer in agricultural fields across the country. For North Carolina, 25-50% of sludge is applied as biosolid to agriculture, according to a map Coffin included in his presentation. With the increase in plastic production, there’s an increase in microplastic concentrations in biosolids, he said.

While it’s known that plants can uptake and accumulate microplastics through their roots and be distributed through their shoots, it’s unknown that plastic particles can make their way into the actual fruits and vegetables that we eat, Coffin explained. “However, we do know that with increasing plastic concentrations in soils, we see decreasing plant production of fruits and vegetables, with above a certain threshold, a complete inability of the plant to create tomatoes in this one study.”

Coffin added that plastic does often contain hazardous chemicals, some of which are intentionally added.

There’s at least 3,300 known chemical additives, 98 are hazardous, and 15 are endocrine disrupting. Bodies create estrogen naturally but when exposed to higher levels, it can cause things like diabetes, intellectual disabilities and cancer.

“Why do we care so much about endocrine disruptors? Exposure to just one class of endocrine disruptors of flame retardants results in more intellectual disabilities than pesticides, mercury and lead combined with an estimated 750,000 to 1.75 million total intellectual disabilities in the United States between 2001 and 2016,” Coffin said. While the human health effects of microplastics are largely uncertain, he said, evidence is rapidly evolving.

Coffin said humans are exposed to microplastics through tap water. Researchers found in 2017 that 94% of samples in the United States had detectable levels of microplastics, prompting California to pass a bill for its Water Board to define microplastics and develop standardized testing.

When it comes to bottled and tap water, in general, higher concentrations are found in bottled water than tap water. “This is not surprising, as the bottle itself seems to be the source of these particles. Just unscrewing a lid from a plastic water bottle releases on the order of 14 to 2,400, plastic particles.”

A recent study also found that polypropylene feeding bottles for infants releases about 16 million particles per liter. This results in the estimated daily exposure of 14,000 to 4.5 million particles per day to infants.

“This is just an exposure, and we don’t know how much risk this could cause,” he said, adding that looking across all exposure routes, air is likely the greatest exposure pathway, with a much higher concentration indoors than outdoors.

Microplastics don’t go away once we’re exposed to them. “It’s estimated that we’re walking around with between 525 and 9.3 million plastic particles. We know that these particles can be transferred to the next generation with four out of six placentas containing microplastics in a 2021 study.”

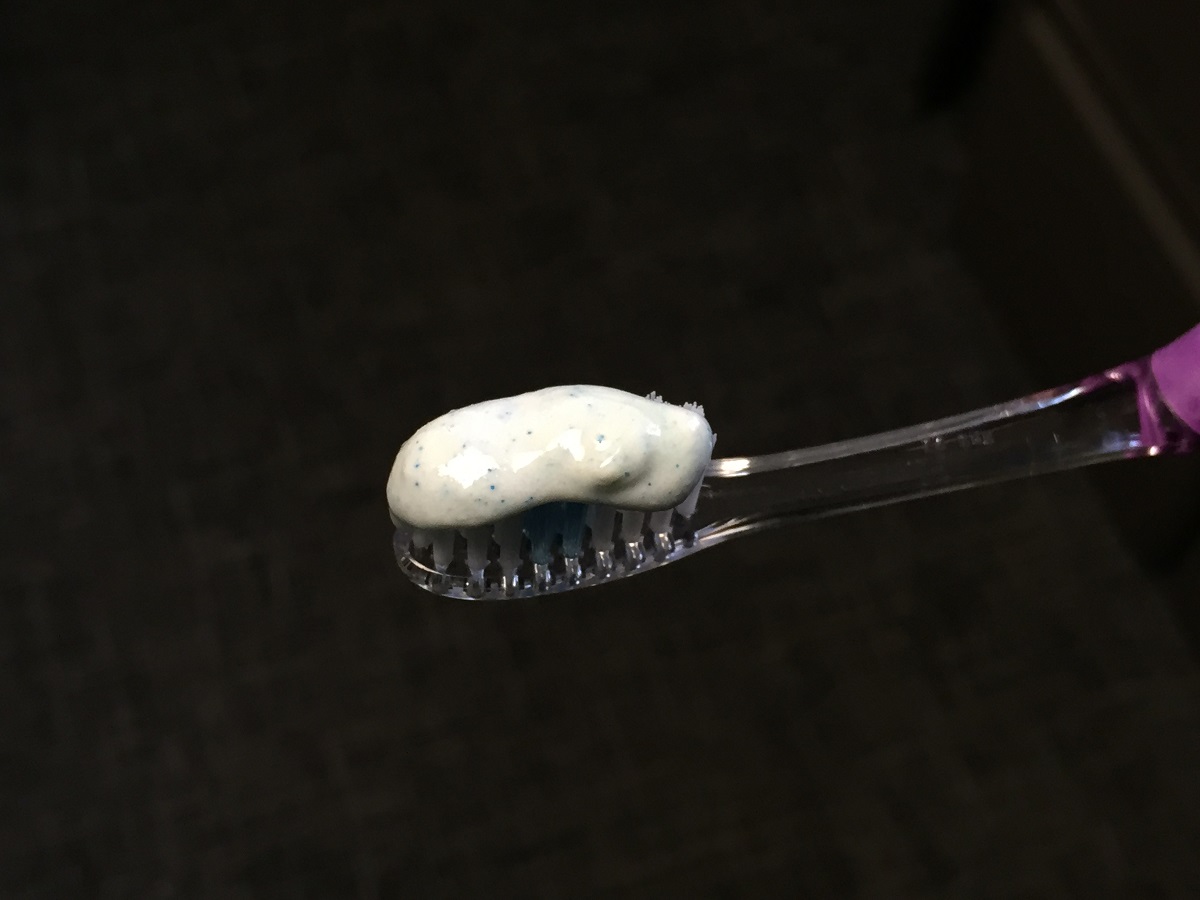

Associate professor at Wake Forest University School of Law, Sarah Morath said in terms of plastic pollution, there are regulatory instruments like bans, such as the 2015 ban on microbeads in beauty products like body wash and toothpaste, economic instruments such as a tax or fee designed to encourage individuals and businesses to alter their behavior, and persuasive instruments, like an education campaign or Plastic Free July which where individuals voluntarily commit to eliminating their use of single-use plastics for a month.

Legislation that has been enacted or is currently being considered at the federal level includes the Save our Seas Act, which tend to get a lot of bipartisan report because they invoke nonregulatory methods, and Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act, reintroduced in March, with mechanisms to address plastic pollution, including putting the onus on the producer to collect and dispose of the product, Morath said. Other acts include the RECYCLE Act that focuses on improving residential recycling programs and RECOVER Act, focused on building recycling infrastructure, both introduced this year.

Zivanovic–Nenadovic told Coastal Review after the forum that this is the federation’s first step in directly addressing the microplastics pollution.

“I hope that the audience was able to gain knowledge about the impacts, magnitude and ubiquity of microplastics. It took decades to get to the point we are in and it will take a determined effort to start to turn the clock back on this problem. We hope to have excited the audience and motivated it to help us as we go forward,” she said. “The audience was able to learn about how pervasive the microplastics are in our environment. The presenters share information about microplastics in our food, in drinking water, elaborated on sampling methods and offered possible policy and regulatory solutions, and examples that exist in other states.”