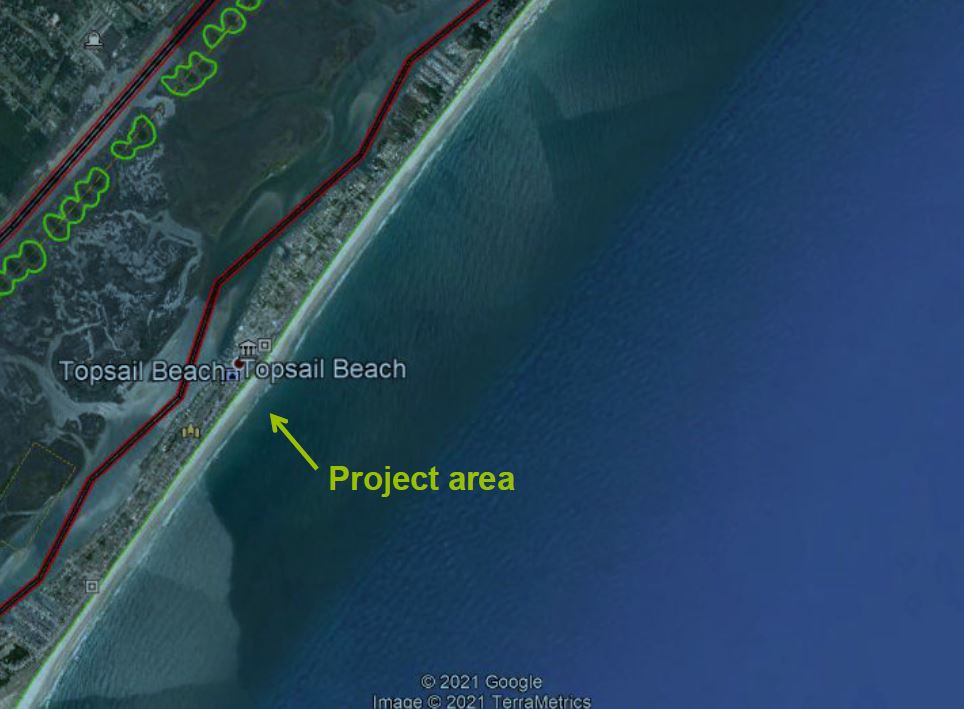

The state Coastal Resources Commission has granted the town of Topsail Beach permission to install beach mats for wheelchair users at three handicapped-accessible beach access sites during the summer months.

The action came during the commission’s regular meeting Wednesday at Beaufort Hotel. The commission sets policy for the state’s coastal management program and adopts rules regarding coastal development.

Supporter Spotlight

“We’re pleased to roll out this blue carpet and to welcome those who are disabled to our beaches to enjoy it,” said Steve Coggins, an attorney who represented the town in the variance request.

The town applied in April for the Coastal Area Management Area minor permit to install the mats for use from May through September. The mats are 5 feet wide and are between 80 feet and 100 feet long. The division in May denied the permit because the mats do not comply with two oceanfront setback rules.

Topsail Beach then sought the variance to continue placing the beach mats for wheelchair access to the dry sand beach, as they’ve done each summer since 2019.

Floating structures

The commission also heard from the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s Ana Zivanovic-Nenadovic, assistant director of policy, on floating structures, which are structures like pilings, gear anchors and floating platforms associated with shellfish leases and may require a CAMA permit.

The commission in recent years has seen increased interest in the floating structures. The division requested new guidance on how limitations detailed in a general policy can be incorporated into a supportive management strategy for the expanding shellfish industry while limiting effects on public trust waters. Under state policy, floating structures are not allowed in coastal public trust waters except in permitted marinas, and all floating structures must conform with local regulations for on-shore sewage treatment.

Supporter Spotlight

Records of shellfish farming in North Carolina date back at least 150 years, Zivanovic-Nenadovic said in noting the cultural and historical significance of aquaculture.

She explained that the North Carolina General Assembly in the last few years had given weight to encouraging the development of private, commercial shellfish cultivation in ways that are compatible with other public trust uses.

About five years ago, the state mandated a stakeholder group look at ways to foster development, which the federation headed up. The North Carolina Shellfish Mariculture Strategic Plan set the goal to grow the industry to $100 million in market value by 2030. Now the industry is between $3 million and $5 million. The General Assembly passed legislation based on recommendations in the plan, she said.

In addition to leading the stakeholder process, the federation developed a feasibility study to learn the industry’s logistical needs, finding that the top impediment to existing growers and the top barrier to entry for new growers is access to prime growing water. This is mainly due to the high cost of waterfront property. Growers also lack work areas, and the federation seeks to establish a hub for shellfish farmers to work and helped develop a low-interest loan program.

Some of the main activities performed on floating structures include harvesting oysters, culling and packaging for market and tagging the bag — all of which must be done under shade.

While this can be done on land, it’s not practical, she said, because of a lack of public access to the water and access to storage and refrigeration in rural areas.

Based on conversations with growers, Zivanovic-Nenadovic said it was determined that a movable floating structure able to fit an oyster grader, power washer and a work area is the biggest need. Benefits include work area, protection from the elements and better product shading.

The commission asked the division staff to research and pursue options to help the growers while also protecting the public trust areas.