Coastal Review is featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

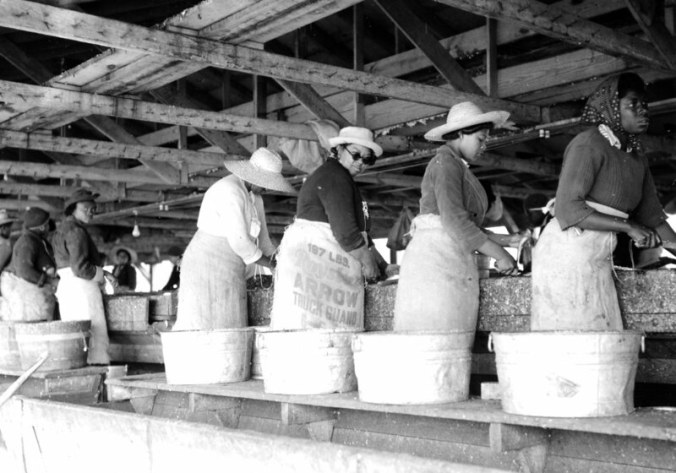

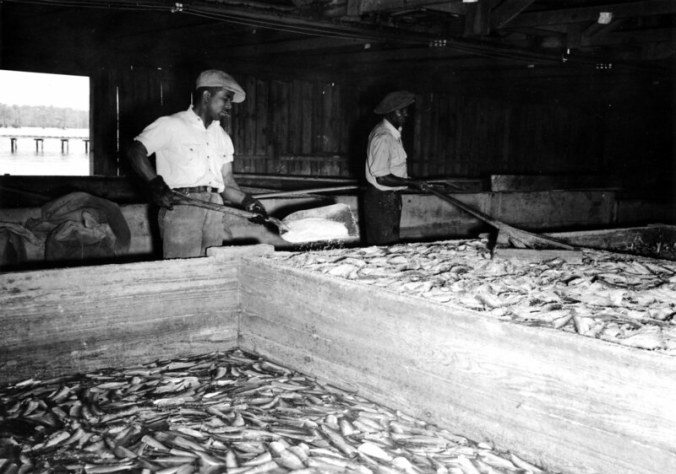

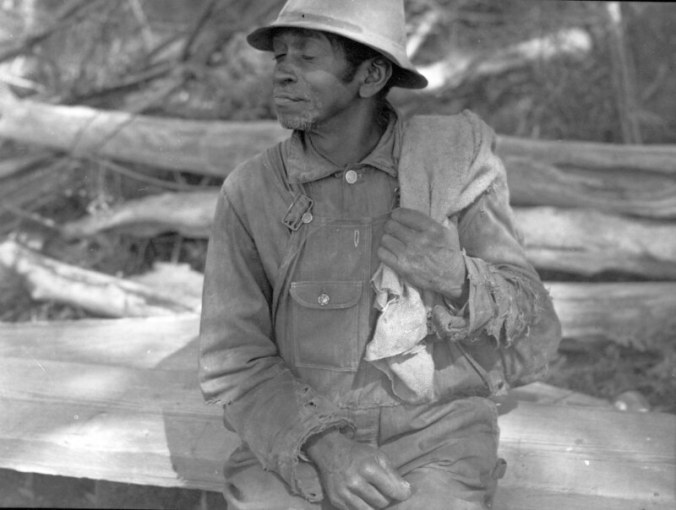

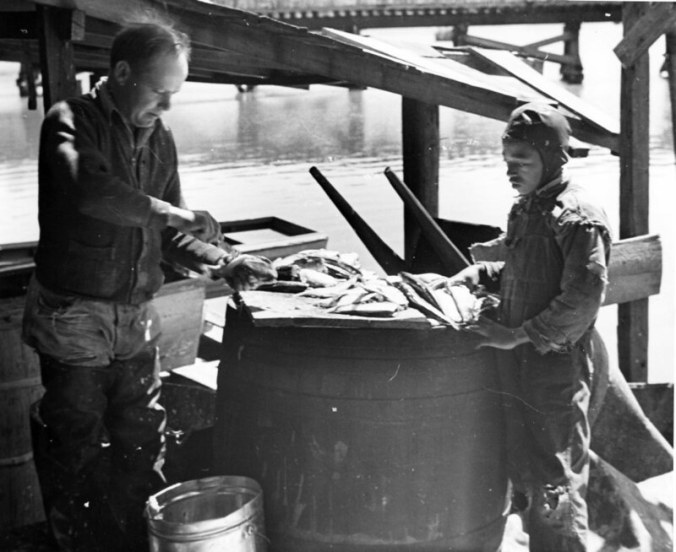

A few years ago, I carried a box of Charles Farrell’s old photographs of the state’s great herring fisheries back to one of the communities on the Chowan River where he took them. The photographs are poignant and beautiful, and the herring workers in them are unforgettable, but I also find them a little haunting because they remind me of all that can be lost.

Supporter Spotlight

Farrell took the photographs between 1937 and 1941. At the time, he was documenting fishing communities up and down the North Carolina coast. Today they are preserved at the State Archives in Raleigh.

When I carried the photographs to the Chowan River, I was trying to find anyone at all that might be able to identify some of the people in them or tell me what it had been like to work in those legendary herring fisheries.

Herring had been important on the Chowan River for thousands of years. The Chowanoke, an Algonquin-speaking tribe, had fished for herring on the river for ages, and before them other indigenous people.

When the British took the land, they fished for herring, too. They had started commercial fishing on the river in the mid-1700s. Enslaved laborers from Africa and their descendants did most of the fishing and the shore work.

From the late 1700s until nearly the end of the 20th century, the river was home to one of the largest commercial fisheries for river herring in the U.S. Some say it was the largest in the world for a great part of that time. Local fishermen once caught millions of tons of herring a year on the river.

Supporter Spotlight

In a five-year period, between 1878 and 1883, a single fishery on the Chowan River harvested 15 million herring.

Even a century later, the herring were still coming. I’ll never forget visiting one of my favorite historians, Alice Eley Jones, on the Chowan River back in the 1990s. After living in the Raleigh-Durham area for many years, she had returned to her hometown of Murfreesboro, on the upper part of the river. Alice and I drove all around the river and its creeks that day while she talked about the importance of herring in the area’s history.

“Fish literally clogged these streams,” Alice told me. She was talking about when she was a girl. “You could wade into Vaughan Creek and pick them up with your hand or a bucket. It’s not like it was one or two fish. It was millions of fish!”

She went on:

“Everybody went herring fishing. Some would have dip nets. Some would have bow nets. People would go down here, catch the fish, clean the fish and fry the fish right on the shore. Churches would go. It was a community event, a time of fellowship and community.”

That has changed. The herring fishery suffered a slow decline during much of the 20th century and it collapsed completely in the 1980s and ’90s — a victim of increasingly poor water quality, grave habitat loss and probably at least a measure of overfishing both on inland waters and out in the Atlantic.

In a desperate gambit, state regulators closed the herring fishery altogether in 2007. For the first time in history, nobody could legally catch a herring on the Chowan River. The regulators hoped that the herring might come back on their own if they were not being harvested at all. The fishery is still closed on the Chowan River and throughout the state’s waters.

Charles Farrell’s photographs remind us of a different time though, and perhaps they also give us a vision of what could be again if the river is restored to health. When Farrell visited the Chowan, great shoals of herring still migrated out of the Atlantic at the end of every winter and swam up into the Albemarle Sound and its tributaries to spawn.

The fish companies sent fresh herring, salted herring and canned herring roe far and wide, but herring were also a staff of life for people who lived on the river.

In hard times I don’t know how they would have survived without them. Few winter pantries did not have a keg or two of salt herring in them, and some families ate herring and sometimes not much else for breakfast, lunch and supper.

Many of the oldest people I know in that part of the state recall making long trips to the Chowan River to purchase herring when they were young. Many families made the journey on Easter Monday, which was always a festive time at the herring beaches. Farmers brought carts, too. They often purchased “trash fish” and offal and carried them back home to use as fertilizer on their fields.

Some paid in cash. Others traded corn from their fields, a country ham or a mess of collard greens.

For fishermen and shore laborers alike, their work in the herring fishery was only seasonal. The fish’s spawning runs usually lasted about three months, roughly from mid-February into May. Most of the men returned to farms or timber mills or something like that for the rest of the year. Many of the women shore workers that we see in Farrell’s photographs probably returned to domestic work and/or worked in other people’s fields.

These photographs came from at least two sites on the Chowan River. One was the Perry-Belch herring company in Colerain, a small town on the west side of the river in Bertie County. Most local people today remember it as the Perry-Wynn Fish Co. The ownership and name changed in 1952.

The other site is a herring fishing beach called Cannons Ferry. That beach is located on the edge of a hamlet called Tyner, which is on the other side of the river in Chowan County.

In addition to the photographs from the Chowan River, I’m also including here photographs from three other herring fisheries that Farrell visited on that part of the North Carolina coast. They include the Brickell fishery near Edenton, the Terrapin Point fishery at the mouth of the Cashie River and the Kitty Hawk and/or Slades fishery in Plymouth, on the Roanoke River. All five fisheries are located within 25 miles of one another.

* * *

One of the things I like most about Charles Farrell’s photographs is that he never forgot how important women and children were to the fishing industry. In all his travels, he paid attention to both the men and women in fishing communities, and also to the children.

For that reason, we often see sides of the commercial fishing industry in Farrell’s photographs that we rarely see in the work of other photographers at that time — or now. He didn’t just visit fishermen, and he didn’t just photograph fishermen with their boats and nets.

Instead, Farrell also directed his camera’s lens toward the women and children heading and gutting fish, canning roe, peeling shrimp, mending nets and shucking oysters. It’s very unusual for that time and for today, too.

I don’t know, but I have wondered how much this focus on women’s work reflected his wife Anne’s influence. They were very much partners in his efforts to document the state’s fishing communities, as in the rest of their lives.

Anne Farrell was very knowledgeable about photography. She was the co-proprietor of their photo supply shop in Greensboro, and she ran the shop on her own for many years after he grew ill in the 1940s. She didn’t always accompany him on his trips to the coast, but she often did.

As I looked through the Charles A. Farrell Collection at the State Archives, I could even tell that she was sometimes the photographer, not him, because he appears in some of the photographs. I couldn’t begin to guess how often she was behind the camera. However, I do assume that she at least occasionally took coastal photographs that are attributed to him. She may also have occasionally influenced her husband’s choice of subjects, though again I don’t really know.

As I look at Farrell’s photographs, I am also struck by the central role that African Americans played in the herring fishery. I won’t say any more about that here, but I think the photographs speak for themselves.

I am a little disappointed that I wasn’t more successful at finding people that could fill in more of the details about the scenes in these photographs. Over the last few years, I’ve been carrying Farrell’s photographs back to the fishing communities where he took them and sharing them with the families of the men and women in the photographs.

I’ve also shared them with many local commercial fishermen and other coastal people that have a knowledge of the kinds of fishing that we see in the photographs. Their insights have been especially helpful in interpreting what is happening in the photographs in a deeper way.

Overall I feel as if I have been fairly successful. I have learned a tremendous amount from many different people who were kind enough to share their time and knowledge with me.

You can see the results in my photo essays featuring Farrell’s work in those other fishing communities. So far I’ve published pieces on the photographs that he took in Colington, Southport and at two sites in Onslow County, a mullet fishing camp at Brown’s Island and a village on the New River that was later destroyed to make way for the construction of Camp Lejeune.

Time has been passing though, and as we all know, time can be very unforgiving when we’re trying to hold onto the voices of the past. So far I have utterly failed at finding the people that might tell me more about these photographs of herring fisheries on the Chowan and elsewhere in northeastern North Carolina. I haven’t given up hope though. Perhaps someone will read this and say something like,” Well gracious, he should talk to my great-aunt Daphne!”

I will be waiting for that call.

* * *

Cannons Ferry seems a bit like a ghost town now. A few years ago, I drove down to that side of the Chowan River to see if I could find anybody that might be able to identify some of the people in Farrell’s photographs. I found a nice little boardwalk with signs that discuss the herring fishery’s history, and there’s a beautiful view of the river. But mostly I remember empty homes, old wharf pilings and a few abandoned cinderblock buildings.

I was hoping that I might even find some of the people that used to work at Cannons Ferry in the 1930s still alive or at least find their children or grandchildren that could tell me about them.

If I did, I hoped that they might be willing to sit a spell and tell me what it was like.

While I was down there, I did meet a group of local fishermen that had just come off the river. (They weren’t herring fishing.) We spread out copies of Farrell’s Chowan River photographs on one of their pickup trucks and looked at them together, which I think we all enjoyed.

They had things to tell me about herring fishing for sure, but every time they thought they might recognize one of the people in a photograph, they’d hesitate and say something like, “Well, they’ve been dead a long time now,” or “Their family moved away a long time ago.”

Cannons Ferry is a beautiful place, though so many of its old homes seem to have been abandoned and all that’s left of the fishery are those old pilings and the remains of old fish sheds. The river’s dark waters are broad there, the shores lined as far as you can see by cypress trees, and you can’t help but feel that you’re on the edge of something great and mysterious and wild.

I was there at dusk and when I looked out on the river, I saw hardly a light. I saw only mile after mile of the cypress glades that mark the edge of the great swamplands that reach north up into the Great Dismal.

Before getting in my car and heading home, I walked up the road a little toward those swamps, passing maybe a half-dozen old fish camps. I could hear a whippoorwill singing not too far off, and I thought about the people in these photographs, and how interesting and how beautiful they all look. As I walked along the shore, I thought I could almost hear their heartbeats.