This is the third installment in a continuing series on making the North Carolina coast more resilient to the effects of climate change, a special reporting project that is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines initiative.

MERRY HILL — At the confluence of the Albemarle Sound and the Chowan River, Bertie County residents celebrated in June 2019 the grand opening of their first public beach.

Supporter Spotlight

Amid the joyous splashing and squeals of laughter, Ron Wesson spied a young girl trying to coax her little brother into the water. The boy would not budge, so the older man gently offered to help.

“We kind of sat there, with our toes in the water,” Wesson recounted in a recent interview. “He held my hand, and I walked out there with him. We took it real slow.”

Within a short time, the little guy found his nerve and was soon playing carefree in the water with the other kids.

Bertie Beach is the community’s first cool gulp of the “Tall Glass of Water,” the working name for the county’s outdoor recreational project.

“It’s weird, though, because I can kind of relate,” Wesson said, referring to the boy’s hesitation and that he and the boy are both Black.

Supporter Spotlight

In 2019, Bertie County was ranked by Wall St. 24/7 analysis as the poorest county in North Carolina. Of its population of 19,000 people, about 68% are Black. Wesson said that, historically, the county has the highest percentage of Blacks in the state.

But the experience that day transcended race, and its implications reverberated beyond Bertie County. The celebration was part of a strategic regional approach to community resilience: Bring the environment to the people and stimulate economic growth through sustainable ecotourism.

After devoting much of his career to study of North Carolina’s barrier islands and sea level rise impacts, Stanley Riggs, a professor emeritus at East Carolina University, has in recent years focused on the inland communities of the Albemarle-Pamlico estuarine system, which comprises sounds and rivers and is threatened by sea level rise and other climate change impacts. Those waterways and surrounding lands offer great opportunity but are considered vastly underutilized.

“That’s one of the world’s great water systems and it’s hardly used,” Riggs said in an interview late last year. “There’s nobody on Alligator River and the whole Albemarle Sound system. There’s precious few people out there.

“We’ve lost several generations of people. Kids have never learned to swim. You take people out on boats and they’re scared to death.”

Riggs is chairman of the North Carolina Land of Water initiative, or NC LOW, and Tall Glass of Water is one of its first success stories.

To Wesson, a county commissioner and Bertie native, the project’s multiyear effort shines new light on the county’s wealth of natural resources.

“It’s about broadening the opportunities and possibilities in a community,” he said. “You have to look at the resources available in a community. This is economic development. This is our brick and mortar.”

Perhaps more than any promotion or lecture could ever do, Tall Glass of Water is showing that climate resilience springs not only from a community’s shared investment in its environment, but also from its shared access to and benefits of that environment.

Its success demonstrates to the entire region that resilience and adaptation to changing climate conditions can enrich communities and open up new economic possibilities, while protecting their environments.

People from all over northeastern North Carolina attended the grand opening of Bertie Beach, said Steve Biggs, Bertie County’s director of economic development, in a recent interview. About 250 people were coming on summer weekends, he said. Swimming, kayaking, canoeing and paddleboarding are all allowed. Eventually, he said, he envisions families traveling to the Outer Banks stopping by for a respite in Bertie.

Biggs explained that the genesis of Tall Glass of Water, or TGOW, was in about 2014, when he was on the lookout for a piece of land for the county to build a boat ramp on the Chowan River. As he was heading into work one day, he said he noticed a “For Sale” sign on some waterfront property.

“I came in and jokingly told the commissioner who happened to be here that morning, ‘So I found your 2 acres for your boat ramp, but it comes with an additional 135 acres,’” Biggs said. As it ended up, the county purchased the 137 acres, he said, and added 10 more later.

Even though Phase I of the TGOW project was stalled by COVID-19 shutdowns, the public outdoor recreation plan has already injected a bolt of energy in talk of ecotourism collaboratives among Albemarle communities.

“We wanted to create a place where folks can spend the day,” now-retired Bertie County manager Scott Sauer said in an interview shortly before the June 29, 2019, opening day. “We think this will be a place that will draw people regionally.”

Not only does the project boast a 3/4-mile stretch of shoreline — 350 feet of which is sandy beach — and shallow, calm water bordered by soundside cliffs where the Chowan River begins, TGOW also includes opportunities for kayaking and canoeing, and will eventually offer a music pavilion, picnic shelters, hiking trails, ramps and walkways, primitive campsites and environmental educational field experiences for students and adults, according to plans. There will also be restoration of the former agricultural land and woodlands, which will help restore the wetlands.

Gov. Roy Cooper announced last September that the TGOW project would receive $500,000 through the North Carolina Parks and Recreation Trust Fund, which awarded $5 million total in grants to fund 16 local parks and recreation projects across the state.

Bertie County’s local match for Phase 1 is $529,591, for a total of $1,029,591.

The county-owned land encompasses Site Y, where archaeologists with the First Colony Foundation recently discovered artifacts that indicate some members of the 1587 Lost Colony relocated there after leaving Roanoke Island.

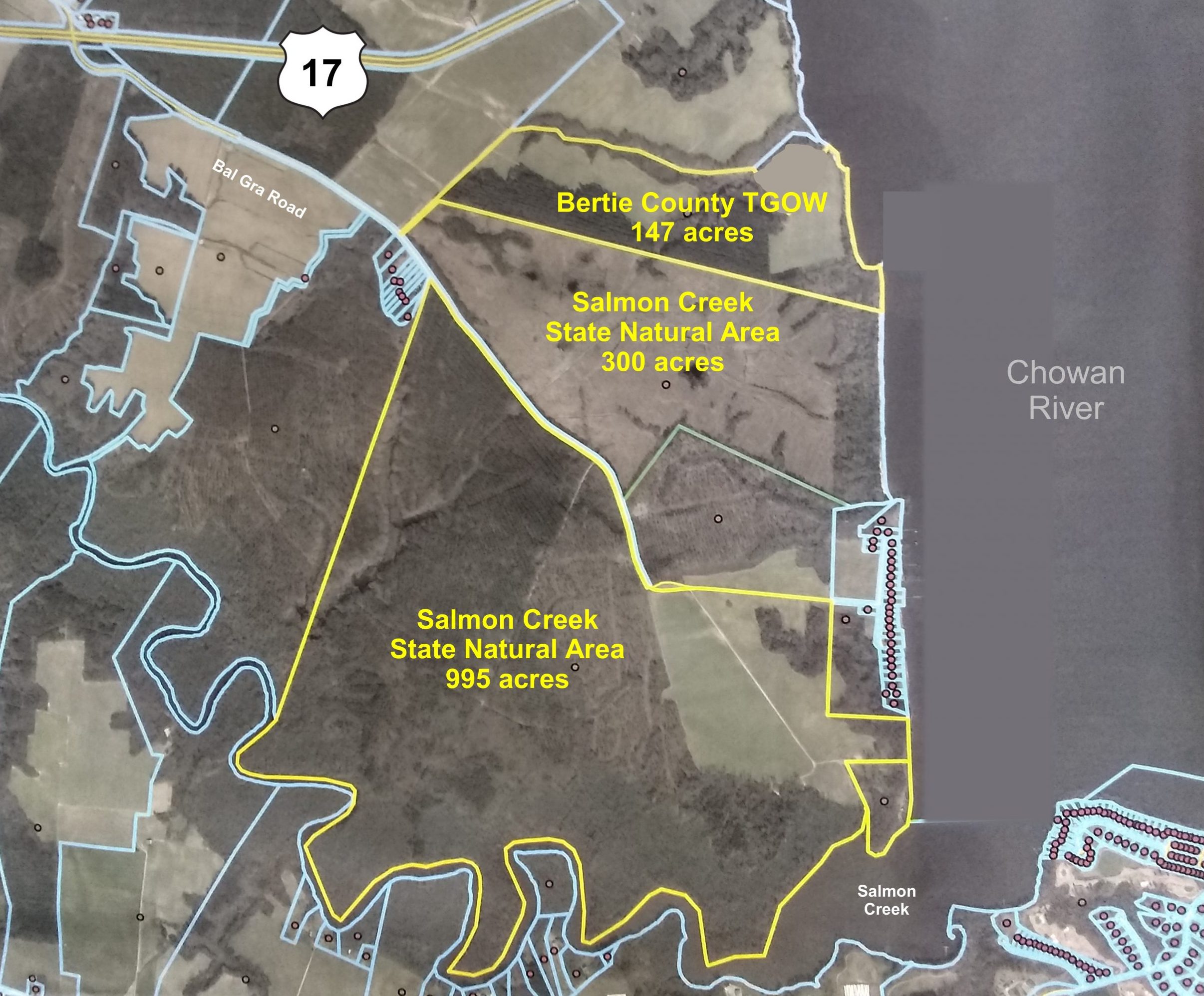

As luck would have it, a large area of adjacent wilderness was protected around the same time as TGOW was hatched. The new, more than 1,200-acre Salmon Creek State Natural Area was purchased for conservation by the nonprofit Coastal Land Trust, which turned it over to the state in 2019. Altogether, a total of 1,432 acres of undeveloped soundfront land is now protected.

Robin Payne, a project consultant for Tall Glass of Water, said that the citizens provided input into the master plan, which was released in March 2020. The project is being built and funded in phases.

“You know, it really all has to be sustainable, and it has to tie together community, environment and economic development,” she told Coastal Review Online last year. “And so, as we move forward, we’re making sure that we connect those three points.”

Until now, unless a family could go to a private pool or beach, it wasn’t a realistic option to enjoy a refreshing dip — especially for African Americans. There are still plenty of kids from Bertie who have never been to the ocean, Wesson said — the Outer Banks is about a 90-minute drive from Windsor.

Wesson, 70, was born and raised in Bertie County before leaving for college and beginning a 32-year career as a corporate executive in supply-management solutions with Dun and Bradstreet.

He returned home about 15 years ago, and he hasn’t forgotten what it feels like as Black kid who had never had the opportunity to swim or go to a beach. He said he didn’t get to swim until he persuaded his mother to take him at age 12 or so to a biracial pool in Rocky Mount, where one of the lifeguards informally taught him the basics of swimming.

“If you’ve never been in the water, other than a bathtub,” he said, “you’re not sure what’s going to happen to you.”

Bertie Beach is the first public access beach not only in the county, he said, but also along the entire Albemarle Sound. To this day, there is no public pool in the area.

Windsor, Bertie’s county seat, suffered extreme flooding from Hurricane Floyd in 1999 and Hurricane Matthew in 2016, but flooding overall has increased in recent years. That realization spurred residents to support efforts to make the town more resilient to flooding.

Biggs, the economic development director, said that more people are elevating their homes and businesses, but he said that, right now, there is not much state or federal help for small businesses. Still, with more people homebound as a result of the pandemic, he said, there is a lot more renovation being done, and the town is continuing to build back.

A farming community by tradition, many residents today work at the Perdue chicken processing plant or at the state correctional facility in Windsor, which houses medium- and maximum-security prisoners. Other folks raise chickens for Perdue or have jobs at Nucor Steel in adjacent Hertford County. The Hope Plantation is in Bertie County, but there are few other tourist attractions. At the same time, there are few chain stores and restaurants.

Bigg noted that more farmers and landowners in the county — as elsewhere in the region — are also leasing their land out for solar farms, which can produce steady income.

Inland coastal counties in North Carolina, especially in the rural northeast corner, are some of the poorest in the state, with losses in population and traditional industries such as timber, farming and fishing, leaving historic old towns with vacant storefronts and entire communities with too few good jobs.

Unlike the Outer Banks’ beach communities that benefit from a billion-dollar annual tourism industry, those communities in the “Inner Banks” — a relatively new term used to describe inland coastal counties —are often overlooked by visitors.

As part of NC LOW efforts, Riggs, the coastal scientist, in 2018 produced a report, “From Rivers to Sounds in the Bertie Water Crescent,” which detailed opportunities for economic development that enhances and protects the environment and culture of the region. That environment encompasses numerous rivers and tributaries with pristine, clear blackwater, filtered by the surrounding peat bogs and wetlands.

In a broader NC LOW report, recommendations include development of five educational and recreational “water hubs” for ecotourism development, with each plan designed for the unique qualities of each hub, but complementary to the whole system.

“All ecosystem components of these different water bodies and their vast swamp forest floodplains,” the report said, “are dominated by numerous forms of wildlife including a vast recreational fisheries resource.”

Within the last 15 years or so, an on-again, off-again proposal to connect the Albemarle port communities with a small ferry operation has been enthusiastically embraced by local governments for its appeal to tourists and as a potential bonanza for economic development. But for various reasons, the idea has never come to fruition. Still, it has never entirely died, and the idea may yet bear fruit.

“Every time anything about it happens, everybody gets excited: ‘When are the boats coming?’” state Rep. Ed Goodwin, R-Chowan, who was also a former director of the state ferry division, said in a recent interview. “I firmly believe that sooner or later, I’ll get it. I believe it will happen.”

A 2018 report “The Harbor Town Project,” a collaborative done by the University of North Carolina Kenan-Flagler Business School, said that a ferry system serving the Albemarle Sound could “increase tourism and create sustainable jobs and careers” and “is an attractive investment opportunity that can become profitable.”

Ferries could serve ports in Elizabeth City, Edenton, Hertford, Plymouth, Columbia and Kitty Hawk, and possibly expand to Windsor, Williamston, Manns Harbor and Manteo, the report said. As many as 140,000 Outer Banks tourists, the report estimated, could be lured to extend their vacation to hop on Inner Banks ferries.

Potentially, the system could garner about $14 million in tourism revenue and create 94 jobs, with annual ridership projected to be 107,000 in the first year.

“Tourists and visitors would enjoy visiting historic towns and sites, seeing nature, and exploring the IBX region by ferry,” the report said, playing off the ubiquitous OBX abbreviation for Outer Banks.

According to news accounts, plans were being made for a 100-foot private passenger vessel to start ferrying passengers between six towns in May 2020. But with COVID-19 shutdowns in mid-March, everything having to do with tourism ground to a halt.

“Everybody is still enthusiastic and wants it done next week, even if it’s an expansion of the current ferry system,” Goodwin said, referring to the state Ferry Division system on the coast.

Goodwin said that he envisions developing routes that highlight the uniqueness of the Albemarle’s environment, while promoting the strength of the region’s rich culture.

“Everybody loves to ride a boat,” he said. “We’ve got to maximize what we have. And what we have is quaint little towns with a lot of history in them.”

Coastal Review Online Assistant Editor Jennifer Allen contributed to this report.

Next in the series: Learning to live with water