EDENTON — The Kadesh African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church is empty, its walls propped up to keep them from collapsing after the church was severely damaged by Hurricane Isabel in 2003. The first steps to bring it back to life have been taken, but it will require around $2 million to repair it, and not all the funds are available yet.

At one time, it was the centerpiece of a thriving African American community. Opening its doors in 1897, the church, with seating for 400 worshippers, stained glass windows and vaulted ceilings, was a testament to faith in God and faith in the community.

Supporter Spotlight

But it was more than that. Until 1928 it was an education center, housing the Edenton Normal and Industrial School, a church-sponsored school for African American students on its grounds. It then became a public school for grades one through seven for the town’s segregated Black community before the school building was torn down in the 1940s.

Norm Brinkley, 91, grew up in Edenton before leaving for college and a career in higher education. His memories of the church recall what it was like.

“Kadesh was such an accomplished church,” he said.

“It was the school and the church,” he continued. “The church had schools in the back. We couldn’t go to other (white) schools that you could attend.”

Even during services on Sunday, the education continued.

Supporter Spotlight

“They made sure that the students — it was almost like going to another school. They had a special table to take a collection for the young kids in church. You were required to read a certain part of the scripture. They would also have you singing in the choir, so that you accomplished a lot of things just by going to church,” he said.

The church on East Gale Street is surrounded by homes built from the 1870s to the 1920s — homes that were at the heart of that African American community.

“This was the African American area. It was a very vibrant community here,” said Dawson Tyler, owner of Down East Preservation in Edenton and a member of the town’s historic commission.

Next door to the church, the Robert Price House was built about 1886, according to a 2007 report from the National Register of Historic Places. The home didn’t look like much when Tyler and his Down East Preservation crew first started working on it.

“Nobody had lived here for 10 years. It was an absolute disaster, and we brought it back to life,” Tyler said.

The house has returned to the look and feel Robert Price created when he built it. The gingerbread roof and hip-roof porch once again face the road. When workers took the modern siding off the building, they found the original wooden siding — damaged, but largely intact.

“We decided to address most of the big gaps at the board and batten. Then once we painted … and caulked it, it was watertight,” Tyler said.

Hidden treasures

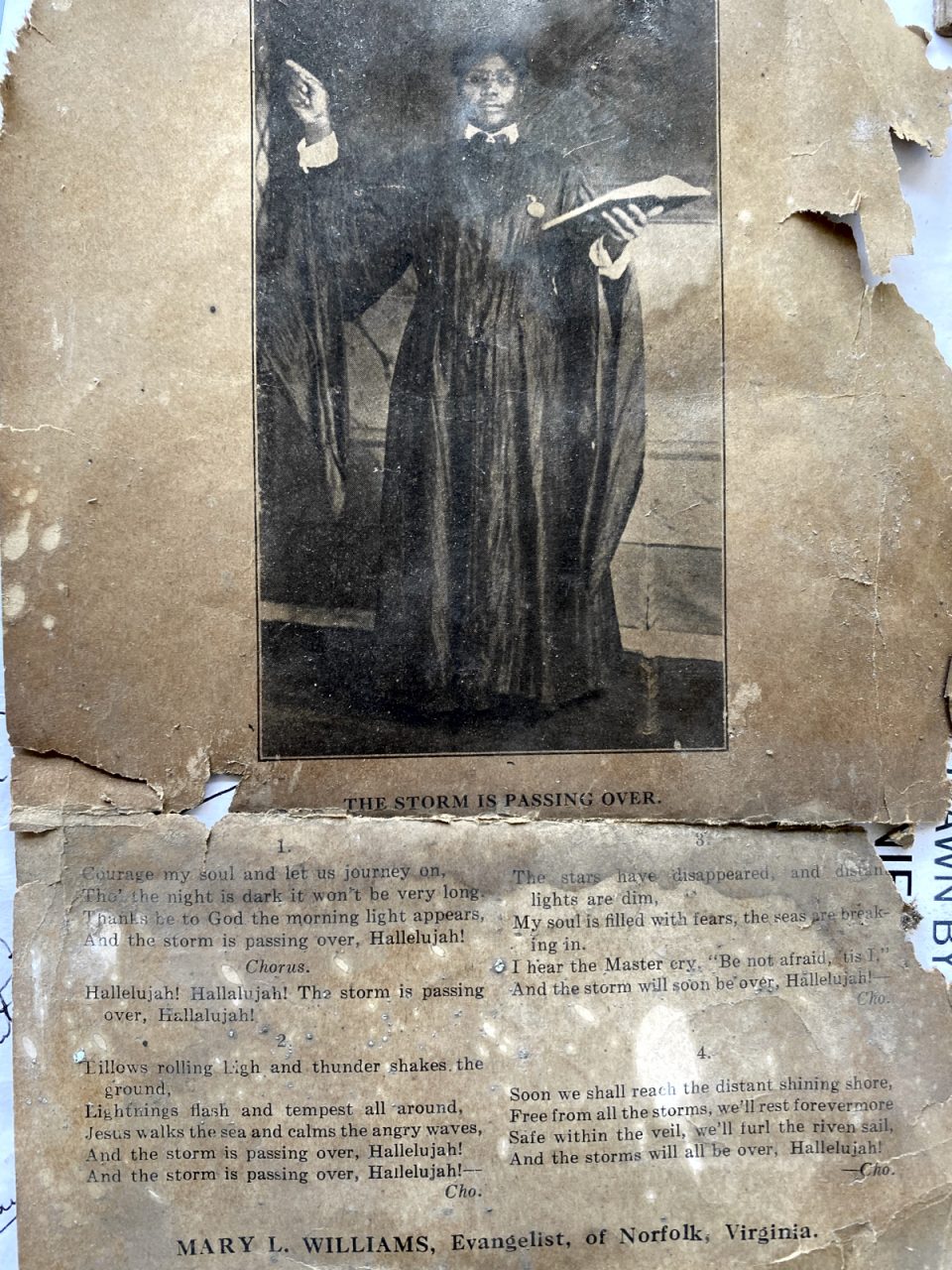

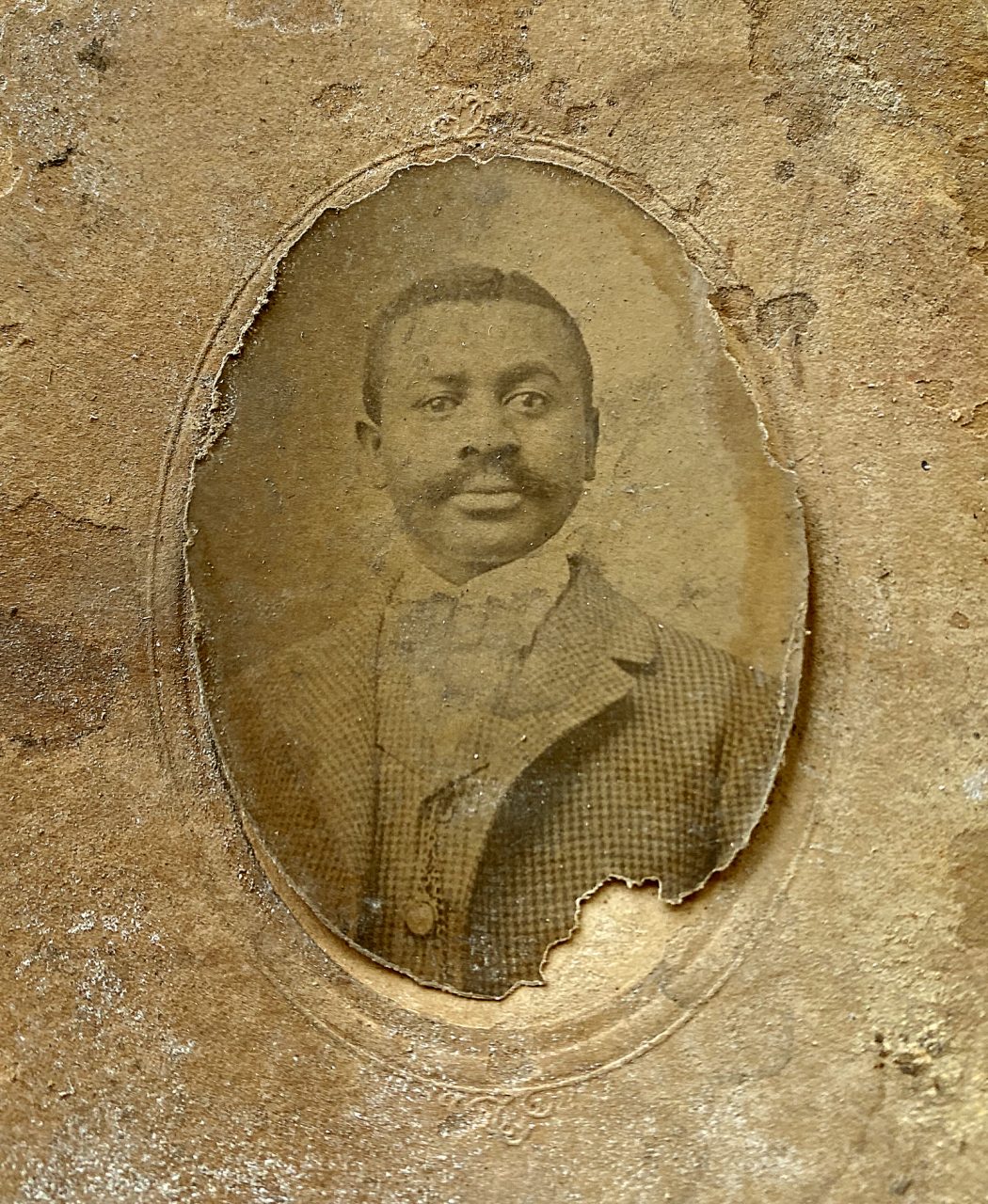

There were surprises in the house. Behind the mantle in the living room, workers found what looked like black and white family portraits. That and a bottle of whiskey imported from Canada with an Old Crow label on it—almost certainly bootleg whiskey from Prohibition.

A little way up the road, at the corner of East Gale and Oakum Street, the Freeman Granby House is a completed project by Down East Preservation. It is unclear who built the home, but it shows remarkable sophistication in design. There is a porch that runs the length of the front of the house with a second-story balcony above it.

There was another surprise in the house that Tyler found when his crew started working on it. The National Historic Places report places the construction date around 1910, but workers found evidence of an earlier structure.

The interior stairs and roof were built for smaller people.

“They were designed for someone 5-foot, 5,” Tyler said. “People were shorter back then (1910). They weren’t that much shorter. They bumped out the part of the house that has the stairs from the earlier structure.”

Although it is not always clear who built homes in the African American neighborhoods, East Gale Street may be a tribute to the Badham family, perhaps the most prolific builders in Edenton during the 19th and early 20th century.

According to the 2007 National Register of Historic Places report, many of the homes built in Edenton were the work of Miles Badham and his descendants.

“The black carpenter whose talent had the broadest impact on Edenton is Miles Badham, a former slave on Hayes Plantation,” the report’s author, Michelle Michael, wrote. “He is known … for the building tradition that he passed on to his son and grandsons. Hannibal Badham Sr. (1845-1918) and his grandsons, Miles (1877-1925) and Hannibal Jr. (1879-1941).”

Examples of the Badham style of architecture line East Gale Street. Just up the street from the Kadesh Church is the 1888 Hannibal Badham Sr. House and next to it, the Evelina Badham School. Across the street from the Price house is a meticulously maintained single-story, yellow-frame home, the Badham House, built in 1890. Next to it is the Hannibal Badham Jr. House, a complex, Queen Anne-style home with a corner turret and wraparound porch.

It was the Badham family that built the Kadesh A.M.E. Zion Church — Hannibal Sr., and his sons, Hannibal Jr. and Miles.

The Badhams, Robert Price and the other African American builders had the skills to create ornate and remarkably well-built homes and buildings. The roots of those skills are found in the business of enslavement.

“In North Carolina, as in other states … Enslaved artisans provided skills in all the building trades, and they worked in various settings … highly restricted and relatively independent. At the same time, free black artisans contended with the curious mixture of autonomy and restrictions imposed by antebellum law,” Catherine W. Bishir, wrote in “Black Builders in Antebellum North Carolina,” a 1984 article written for the North Carolina Office of Archives and History.

The lives of Robert Price and Hannibal Badham offer a glimpse into both worlds.

Price, according to the 2007 National Register of Historic Places report, was the son of “a free black carpenter named Joseph Price (who) purchased a lot where his son, Robert Price, also a carpenter, would build himself a residence, ca. 1886 …”

Price was one of 17 Black carpenters listed in the 1880 census in Edenton. There was only one white carpenter.

It is apparent that following the Civil War, the African American population of Edenton enjoyed a thriving economy. The Reconstruction Acts of 1867, guaranteeing the right to vote for Black men, was important in creating opportunity. A provision in the Reconstruction Acts required states to ratify the 14th Amendment, granting civil rights protection for African American citizens and further providing Blacks a say in their futures.

But the prosperity enjoyed by the African American community was short-lived. Beginning in 1877, Southern states began passing legislation regulating where Blacks could live, restricting their freedom of movement and interaction with whites — the Jim Crow laws.

As the laws became more prohibitive and entrenched in society, the economic effects became more apparent.

“Economic opportunity was further restricted by individual and institutionalized racism and political disenfranchisement. Discrimination in hiring by employers and intimidation of black workers through violence placed black workers at a direct disadvantage in the labor market,” Trevon Logan Peter Temin wrote in “Inclusive American Economic History: Containing Slaves, Freedmen, Jim Crow Laws, and the Great Migration,” a working paper written for the Institute for New Economic Thinking.

Edenton, with its fisheries and lumber mills, was able to retain some of the economic vitality of the Black community into the 1930s. Yet, as Brinkley recounts, it was hardly a level playing field.

“We had a lumber mill here … My father worked over there, and he got sick,” he said. “And there wasn’t anybody at the mill who could run the saw he was running. When he got sick, they had to go all the way to Columbia, North Carolina, and they brought a white person in to do his work while he was away.”

His father’s Black coworkers discovered the white man was getting paid more than Brinkley’s father, and they let him know.

“It bothered Daddy so bad, he went to Mr. Brown, who owned the mill, and said, ‘Mr. Brown, you need to pay me more money.’ And Mr. Brown said, ‘Norman, I can’t do that.’ And my daddy said then he’ll quit. And when you quit one job for a white person in Edenton, you wouldn’t get another white person to offer you a job,” he said.

His father started doing the only thing he could do.

“He started working for himself. He was a carpenter and he ended up making more money than if he had stayed there. You know, it worked out better for him,” Brinkley added.