James Hargrove is an environmental consultant and the owner of Middle Sound Mariculture, an oyster company in New Hanover County. But he’s not always out tending to his oysters. More and more, he’s at his computer, looking at maps.

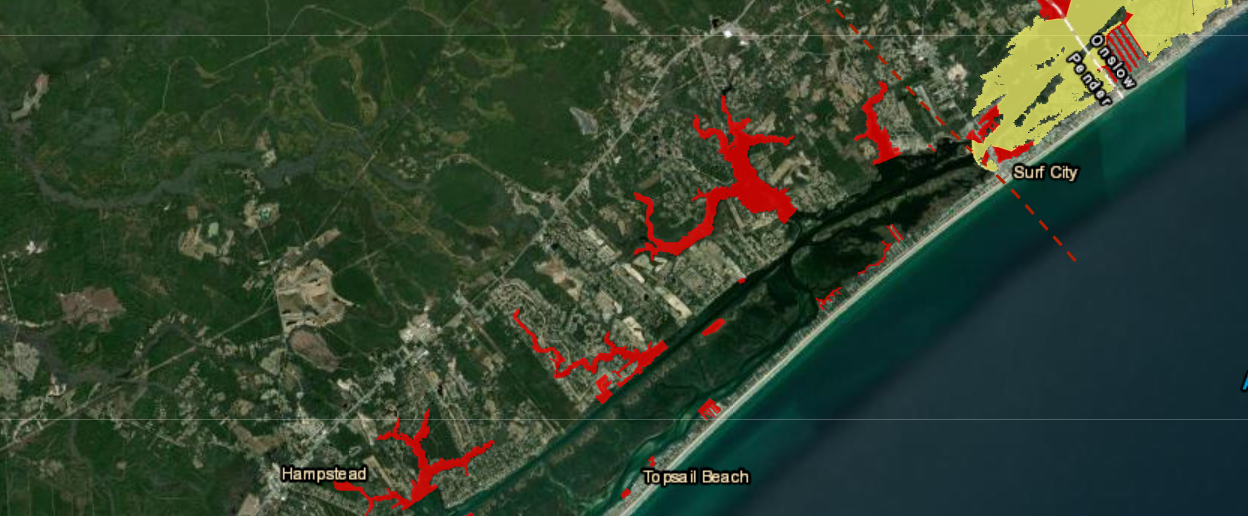

These maps show water closures across the state. After a body of water reaches a certain level of pollution, the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries closes it to shellfish harvest. On the maps, these closures show up as little red lines.

Supporter Spotlight

As pollution in the area worsens, Hargrove has watched these little red lines creep farther and farther out from the shoreline and creeks — and closer and closer to his oyster farm.

“Those lines move, and they move in a relatively frequent basis,” said Hargrove. “There’s one that scares the heck out of me, which is pretty close to my farm in Masonboro Sound.”

For all this worry, it’s nothing new. This is just another day in the “Napa Valley of Oysters.”

That nickname is an allusion to North Carolina’s ample shellfish farming waters, as well as the recent swell of new farmers to the industry.

Over the last decade, North Carolina has helped promote a shellfish economy through legislation that more easily enables shellfish aquaculture. In response, the industry has grown substantially. The North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries reports that the amount of shellfish lease applications they have received has increased by 5,200% in the last five years, compared to the previous five years.

Supporter Spotlight

But in a water-based industry, poor water quality can be a death sentence. Hargrove worries that the shellfish relay program will ax the very industry the state is trying so hard to promote.

North Carolina’s shellfish relay program is more than 100 years old. A shellfish relay is when a farmer takes natural oysters from a polluted area and brings them back to their individual lease. After a couple of weeks, the oysters have cleaned themselves, and the farmer can sell them commercially.

Over the last decade, there has been a land-based development boom up and down the North Carolina coast. Hargrove said this development, along with concentrated animal farming operations just to the west, is causing a water quality crisis in the state, and he worries that the relay program makes his shellfish farm more vulnerable to encroaching polluted waters.

Oysters are natural water filters, and they purify the water simply by existing. Hargrove says that removing the ecosystem’s natural line of defense is exacerbating the issue of poor water quality in North Carolina.

Hargrove has raised his concerns to government officials many times over the last few years, but they always get brushed off as inconsequential.

Division of Marine Fisheries Section Chief of Habitat and Enhancement Jacob Boyd agreed that North Carolina has a water quality issue, but he doesn’t think the relay program has anything to do with it.

“A lot of these are waters that are so polluted anyway, you can take every oyster out of there or put 5 million oysters in there and it’s not going to make a difference,” said Boyd. “You can’t oyster your way out of water quality issues.”

However, even though Boyd said he doesn’t think the relay program should be disbanded because of environmental concerns, he also is unconvinced that it will be around much longer anyway.

“It’s really a shell of what it used to be, and I don’t really see it going back,” said Boyd.

Boyd explained that the relay program was initiated to help bottom-lease oyster farmers be more productive. But modern technology and the popularity of vertical water column leases make the relay program less and less relevant.

And because of new regulations by the National Shellfish Sanitation Program, relay farmers must be escorted from polluted tidal creeks to their own leases by the North Carolina Marine Patrol. Boyd said that’s a lot of resources to allocate to just one program.

He said the department is informally evaluating the practice and will continue to do so. Eventually, it just might not be viable anymore.

For oyster farmer Keith Walls, that day can’t come soon enough.

Walls is a marine scientist, and sees the relay program as a direct threat to his oyster operation, Falling Tide Oyster Co. He said that if the state is going to promote the growth of the commercial shellfish industry, it needs to find ways to protect it.

He points to the actual Napa Valley. When expansion from San Francisco posed a threat to the region’s fertile land, it became the country’s first agriculture preserve. This not only protected the industry but the environment as well.

Walls doesn’t expect anything similar in North Carolina, but he said that removing the relay program would be a good start. Or at the very least, he thinks the relay program could be managed differently to mitigate the environmental effects. By rotating relayed areas or subsidizing relay farmers with funds for oyster seed, Walls says he would see the relay program as less of a threat.

There’s little research on the actual effects of the relay program. This is a knowledge gap that Walls said needs to be filled to determine if any additional actions need to be taken. He only hopes it won’t be too late.

“The lifeblood of our industry is water quality,” said Walls. “Without it, we have no industry.”