As population growth makes the expansion of traditional farming without severe ecological damage more and more challenging, scientists are looking to the sea as one potential solution.

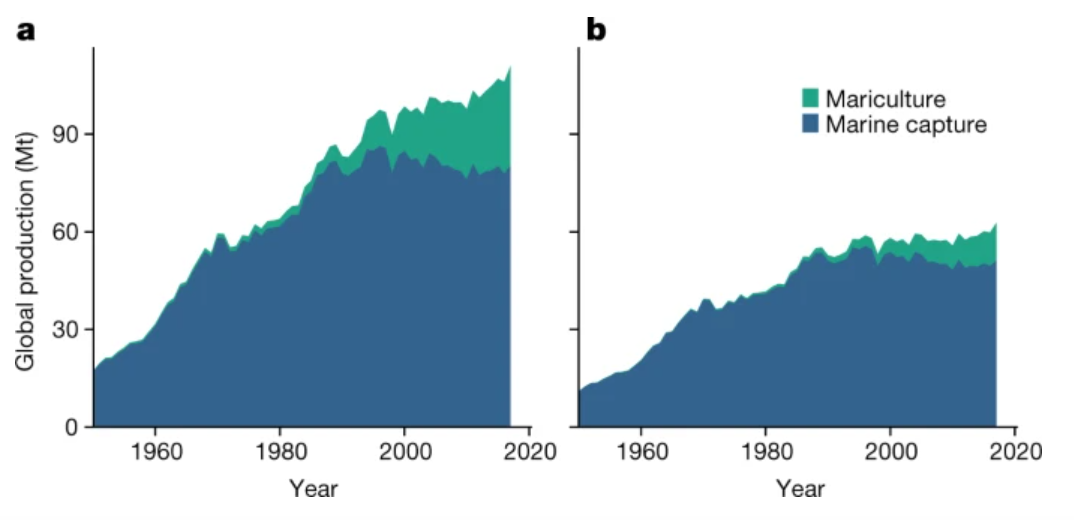

A recent study published in Nature projects that the amount of food sustainably produced by the ocean could increase up to 74% by 2050. But researchers say that there are substantial obstacles to bringing in more food from the sea, obstacles that have little to do with fishing and more to do with policy and regulation.

Supporter Spotlight

This concern hits home for North Carolina’s shellfish mariculture farmers like Jay Styron, of Carolina Mariculture Co.

“The biggest issue we are going to have is public perception and public policy,” said Styron.

Styron has been in the shellfish mariculture business for upwards of 17 years. According to Styron, shellfish mariculture on the North Carolina coast has only been going at a steady clip for seven or eight years. Despite the industry’s fledgling status, Styron sees enormous potential for growth. And he’s not the only one.

According to the study in Nature, land-based agriculture cannot significantly expand without permanently damaging the ecosystem. The study found that by 2050, the demand for protein will have increased by 500 megatons per year. According to the researchers, limited water, land and declining yields make this an unrealistic goal for traditional farming.

“It’s very hard to tell a story of expanding sustainable production of beef and other land-based animal sources of protein,” said Christopher Costello, a lead researcher on the project. “So where is all this animal protein going to come from?”

Supporter Spotlight

According to researchers, the sea may hold one possible solution.

The researchers analyzed census data from fisheries and farms like Styron’s to make their projections, trying to account for regulatory and economic obstacles along the way. The research team included experts from multiple fields, including ecologists, economists and nutritionists, in order to seek answers to their sustainable food systems questions.

Among these, the researchers sought to find out if sustainable farming and fishing was profitable, and if so, if people would actually want to eat the things produced by sustainable farms or fisheries.

The team found answers in the form of a resounding “yes” and a reluctant “maybe.”

The study projects that sustainable farming and fishing has the potential to increase yields and to do so profitably. But they aren’t certain that’s enough to make a difference in the economic market. For countries like the United States, wholly married to traditional farming and proteins like beef, the shift would be nothing less than a fundamental culture change.

But according to the researchers, the sustainable management of fisheries and the expansion of seafood farming would be paramount in addressing supply problems. For fishing and seafood farming to be viable protein options for the future, there has to be an increase in demand.

According to the study, food from the sea represents 17% of the world’s consumed meat. Parts of the globe, like countries in Southeast Asia, already emphasize fishing and seafood farming in their diets, said Halley Froehlich, part of the research team that produced the study.

But the United States isn’t one of those countries. While the study projects that the ocean could provide more than six times the amount of food it currently produces by 2050, the researchers don’t expect a similar increase in demand.

Changing public perception around protein from the sea as a long–term food option is a complex and political issue, said Froehlich.

“Whether or not people would be willing to trade one thing for another, and how does that mechanism occur … the social dimensions of that from a consumer perspective are quite challenging if the policies are not there,” Froehlich said. According to the study, updated and improved policies could bolster seafood yield and meet sustainability goals.

As an example, Costello recommends taking a look at fisheries.

Many wild fisheries are overfished in order to bring in the maximum yield, Costello said.

He believes that when it comes to these operations, there’s a popular misconception that to sustainably farm means a lesser yield, and therefore, less food for people to eat. This isn’t true at all, he said.

“Actually, by growing those stocks to a larger level (and by) sustainably managing those stocks, eventually you’ll be able to catch more, not less,” Costello said.

James Hargrove, an oyster farmer and owner of Middle Sound Mariculture, agreed.

“Fisheries in North Carolina have been mismanaged and overfished for generations,” said Hargrove. “And we see that with the limited stock that are here now.”

Hargrove has an extensive background in shellfish mariculture. Before he started taking his own leases, he was Secretary of the North Carolina Shellfish Growers Association for four years, and had even done his graduate work in applied mariculture. Now, he works as an environmental consultant when he’s not out tending to his oysters. So he is familiar with the types of policies that small shellfish farmers are up against in North Carolina.

One of these obstacles is submerged land claims. The tussle over who owns land beneath the water’s surface is not new, but it can be inhibitive for shellfish farmers looking to establish leases. Despite the appearance of public water access along the coast, many portions of submerged land are actually pre-owned by someone else.

It is not unheard of that a farmer applies for a lease, only to find out that it was not legally viable due to a submerged land claim.

According to the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s Mariculture Feasibility Study, there were 278 shellfish leases in North Carolina as of 2020. Hargrove figures he’s one of only a small handful that have multiple leases.

He estimated that he’s currently the only farmer with a water-column lease in New Hanover County. Other leases in the region were either not renewed, or due to a state-issued moratorium on new leases for that area, were denied altogether.

There are only a few moratoriums on new leases in North Carolina — but they are one of the things that keep the shellfish industry from expanding. Hargrove is in the middle of his 10-year lease in Masonboro Sound, and hopes that when it’s over, he’ll get to renew it. But ultimately, he’s not sure what will happen.

And then there’s the issue of coastal development.

Hargrove views coastal development as one of the biggest things in the way of sustainable shellfish farms in North Carolina. Some development practices increase runoff and impact water quality. Hargrove is concerned that without a significant policy change, pollution will inhibit the potential for sustainable shellfish farming.

But which has to come first, policy changes, or an increase in demand? Froehlich and Costello are working on other projects to continue the search for sustainable food solutions from the sea, specifically to find answers to questions like these.

While the pathway to the future of food grows more complicated by the second due to climate change and a growing population, Costello recommends people look at their own diet and consider its impact.

“Look to the sea as a possible alternative to what you’re already eating,” Costello said. “Our study and lots of other evidence suggests that it can be done sustainably and is also good for you.”

The nutritionists involved in the study noted that in comparison to beef and other land-based meat, seafood provides more substantial health benefits. It is high in fatty acids, vitamins and nutrients that are essential to human health.

Despite these benefits, oysters and other shellfish are still seen in North Carolina as a luxury item. With the exception of an autumn outdoor roast, most people don’t buy oysters to cook at home. Most of Hargroves’ buyers are restaurants and chefs.

According to Hargrove, culinary professionals are some of the few who seem to care about the story behind each oyster. Flavor variation in each oyster is tremendous, depending on the body of water and fluctuations in the tide.

North Carolina has a lot of this variation, which is why Hargrove and others like to call it “the Napa Valley of Oysters.” But public awareness isn’t quite there yet.

According to Hargrove, the shellfish industry has some reckoning to do. Without substantial policy changes at the state level, he isn’t sure what kind of future shellfish mariculture can have.

It’s a risky business on its own, said Hargrove. Many farms were still recovering from the effects of hurricane damage by the time that COVID-19 hit. With one setback after another, it’s hard to be optimistic about the future of sustainable seafood.

And yet, he is. For all its difficulties, Hargrove believes shellfish mariculture is incredibly rewarding. And he believes the scientists are correct. When it comes to sustainable food solutions, the ocean holds the key.

“I do want to expand this industry, even with the challenges,” said Hargrove. “Myself and others look at it as the ultimate form of protein production. There is no other more sustainable form of protein production.”