Note from the author: This is the first chapter of Shark Hunter: Russell J. Coles at Cape Lookout. The rest of the story will be posted on davidcecelski.com in its entirety over the next few weeks.

A few years ago, a gentleman in Virginia, Walter Coles Sr., invited my daughter and me to visit his family’s archive of research materials related to his uncle, a world-renowned shark hunter named Russell J. Coles who did the bulk of his shark hunting at Cape Lookout between 1900 and 1925.

Supporter Spotlight

The invitation was extremely generous. Russell Jordan Coles was a fascinating figure. Every summer for that quarter century, he left his tobacco brokerage in Danville, Virginia, and moved onto a houseboat in the quiet waters of Cape Lookout’s bight.

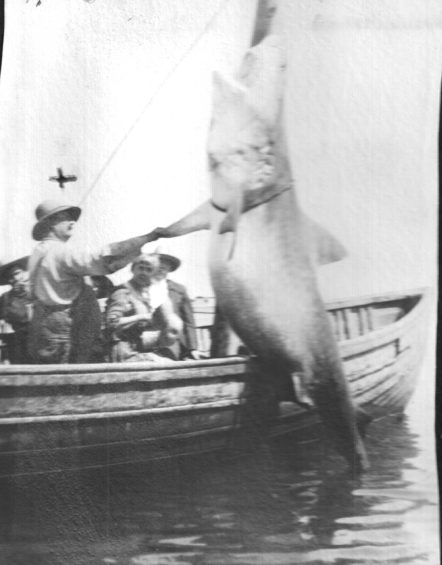

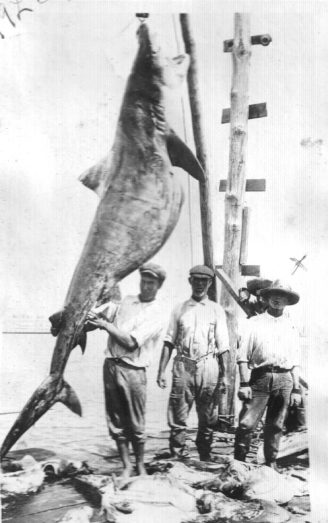

While there, he grew obsessed with sharks. At first he pursued them with rod and reel. Later, he hunted them with lances and harpoons, and eventually he even employed heavy nets and trot lines. Over the years, he hunted and killed hundreds and possibly thousands of great whites, hammerheads, tiger, thresher, nurse and other sharks at and near Cape Lookout.

Of course one can look at that kind of slaughter as a multitude of acts of great courage and feats of death-defying daring or as acts of brutal carnage and ecological ruin. It might have been both.

Coles was not only a big game fisherman though. He had studied a little medicine before he left — or was asked to leave — the Virginia Military Institute after a prank in which he tried to blow up the school’s arsenal with an extraordinarily large quantity of dynamite. He never finished his degree and he had no training in ichthyology, or the scientific study of fish, at all.

Yet sharks and rays fascinated him and he probably observed them in their natural habitat as much or more than any other man on Earth.

Supporter Spotlight

He came to Cape Lookout seeking to test his manhood and collect trophies. But the sharks and rays got under his skin and he soon began to study their habits in the wild. After building a laboratory on his houseboat, he even began dissecting his fallen prey and studying its anatomy and physiology.

At that time, the scientific study of sharks and rays was still in its infancy. Very few biologists had studied sharks in the wild, the first scientific study of shark behavior was yet to be written and many leading shark experts knew them only as preserved specimens.

By virtue of his field experience, Coles was uniquely well placed to make a pioneering contribution to the field.

By 1910, several of the most knowledgeable shark experts at museums and universities in both the U.S. and Europe were corresponding with him and he had become one of the country’s leading authorities on sharks and rays.

He developed an especially strong relationship with the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

To this day, marine scientists on both sides of the Atlantic use specimens that he collected at Cape Lookout in their research.

Marine biologists also continue to use his scientific writings, and even marine biology students learn about at least one aspect of his research — his pioneering observations on the cooperative hunting behavior of sharks.

At Coles Hill

My daughter, Vera Cecelski, who is also a historian, and I accepted the invitation of Russell Coles’ nephew Walter Coles Sr. and his wife Alice with great gratitude. To our knowledge, no other scholars had previously been granted access to the family’s archive.

In the winter and spring of 2014, we made two trips to Coles Hill, the family’s ancestral estate in Chatham, Virginia.

Today, Coles Hill is a beautiful place with quiet country roads and hundreds of acres of broad pastureland, fields and orchards.

The family has been at the center of a controversial proposal to build a uranium mining and milling facility at Coles Hill, however. You can get a taste of that controversy in articles in The Washington Post here and in Bloomberg News here.

Chatham is a small town in the south-central part of the state, in the lovely rolling hill country between Danville and Lynchburg.

The library occupies a room in the Coles’ home, a Georgian brick manor built circa 1817 just outside of Chatham.

The family’s roots run deep into America’s history. George Washington stayed with Russell Coles’ grandfather on his southern tour in 1791. James Madison signed that grandfather’s commission in the army, and Thomas Jefferson signed the family’s land grant.

The house is built of Flemish bond brick made at Coles Hill, presumably by enslaved laborers, and on one side of the mansion are gardens that lead down to the family’s burial ground.

Inside, Vera and I marveled at the family’s treasures, including one of the hand-forged harpoons that Russell Coles used to hunt sharks and giant manta rays and a breathtaking collection of antebellum furniture built by the great African American furniture maker Thomas Day of Milton.

After visiting with the Coles and hearing several family stories about Walter Coles Sr.’s Uncle Russell, we settled into the archival materials from their library.

The Teddy Roosevelt Letters

As Vera and I plunged into the family’s library, we quickly discovered that the collection of materials on Russell Coles is matchless. It includes his journals and diaries, reams of private correspondence, unpublished writings, many photographs and an assortment of field notes on his observations of sharks, rays and other marine fishes at Cape Lookout.

It also includes copies of the articles that Coles published in natural history journals and magazines, some of which are now quite hard to find, as well as albums of newspaper clippings about him.

Russell Coles was also a close friend of Teddy Roosevelt’s. I imagine many scholars would consider the letters between Coles and Roosevelt to be the collection’s highlight.

In those letters, Roosevelt and Coles discussed their plans for a giant manta ray hunting expedition in Florida, their dream of fighting in World War I with a battalion of old codgers like themselves and much else.

Even when I wasn’t reading their letters, I often thought of Teddy as I browsed Coles’ papers. The two men’s physical resemblance, for one thing, is striking, though I noticed that his contemporaries more often compared Coles’ appearance to that of President Taft.

But more relevantly, the great themes in Roosevelt and Coles’ lives often seem to have been one and the same.

Both had an unquenchable thirst for adventure and exploration and an avid curiosity about the natural world.

Both possessed indomitable wills and unyielding, often reckless desires to hunt and conquer, and not just sharks and other wild animals. Both had tremendous appetites for life that could not be satisfied.

Both men also felt a never-ending restlessness. They had urgent, boundless needs to know what was most primeval in their own hearts and, I think some would say, to steel themselves against the things they feared most.

They spoke the language of colonizers and imperialists: to explore, conquer and hold dominion.

No matter how frail they grew in old age, even when Roosevelt neared his end and could barely get out of bed, the two men still shared a dream of taking up arms and going to Cape Lookout to fight monsters in the sea.

A Man with a Harpoon

When Vera and I said goodbye to our extraordinarily kind hosts and left Coles Hill for the last time, our heads were full of a hundred images.

Now, several years later, one of those images stands out most to me: Coles, the aging hunter, rising on his houseboat in the early morning light, as he did again and again, and taking a whaleboat into the breakers several miles out along the great shoal south of the island’s lighthouse.

Large numbers of sharks congregated along that shoal. Coles would stand in the whaleboat’s prow with his harpoon, made by his own hands in his own forge, and go after them until he was exhausted and the sea blood red.

He would do this for an hour or two, and then he would come back to the houseboat and have his breakfast.

At Coles Hill, Vera and I learned about a great many other parts of his life, but when I think of Coles, I picture him on that shoal: the lone boat, the dark red waves, the great sharks and a man, far from young, wielding a harpoon, striking left and right, left and right, as if nothing else in the world could make a man feel more alive.

Coastal Review Online is featuring the work of historian David Cecelski, who writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.