Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

Last of three parts

Supporter Spotlight

Like a solar eclipse, a dark shadow crept over the towns of the Pamlico a few weeks after they had been visited by Sir Richard Grenville’s 1585 expedition. Expedition scientist, ethnographer and Algonquian translator Thomas Harriot wrote this general observation in his “Brief and True Report:”

” … within a few dayes after our departure from everie such towne, the people began to die very fast, and many in short space; in some townes about twentie, in some fourtie, in some sixtie, & in one sixe score, which in trueth was very manie in respect of their numbers … The disease also was so strange, that they neither knew what it was, nor how to cure it.”

Harriot observed that the mysterious sickness devastating some Algonquian towns had not occurred where they had not visited. The Native Americans wondered if the English were able to kill them without weapons. Rumors spread amongst the towns and even between neighboring nations of Iroquoian and Siouan language groups, that the strangers from across the sea with their invisible weapons were to be avoided or killed on sight.

On the Pamlico River on Friday, July 16, 1585, after departing from Secotan, Grenville’s expedition made its way back down to the sound following the same compass heading and passing the same creeks, points and bays as Beaufort County boaters do today. Along the way, their survey continued of the mainland, even if it was not as detailed as the Hyde County shoreline. South Dividing Creek, with its distinctive southwestward course, is plainly shown on White’s watercolor map.

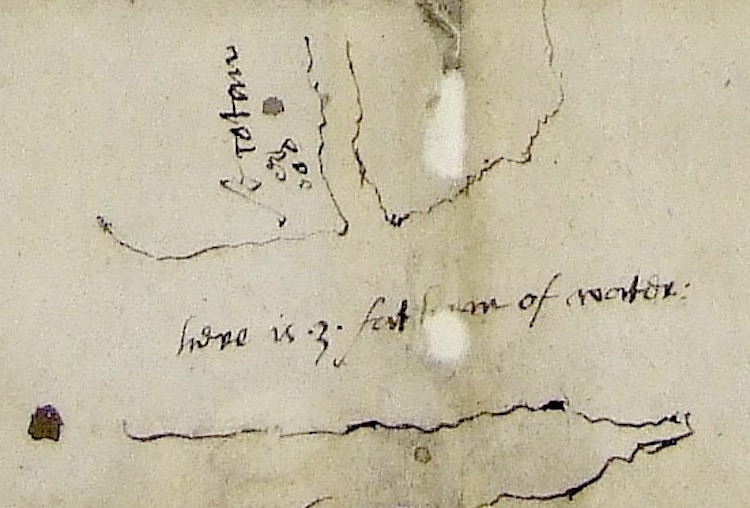

Down river of Bath Creek, according to the anonymous sketch map, they also recorded the only soundings of the entire expedition — further evidence that Secotan was not on Pungo River. It was, in fact, the only water depth shown on any of the three maps made during the entire four-year span of the Roanoke Voyages, even though they had taken soundings everywhere they went. They measured 18 feet of water in the middle of the Pamlico River. This depth compares to an average of 15 to 16 feet today.

Supporter Spotlight

One might think that with sea level rise over 435 years, the river would be deeper today than it was in 1585. However, centuries of farming and mining along the Tar-Pamlico estuary has filled the river with silt. Similarly, when Bath Creek was surveyed in 1979 by a team of professors and students from East Carolina University, it was determined that as much as 6 to 15 vertical feet of viscous sediment covered the once pristine sandy bottom of the creek.

At some point during their time at Secotan, one of Grenville’s men noticed that they were missing a silver cup, perhaps a communion chalice, that was last seen when they were at the Algonquian town of Aquascogoc earlier that week.

Before exiting the river, Grenville sent Capt. Philip Amadas, likely with Manteo, the Croatoan, to return to the Pantego Creek town to ask that the cup be returned.

Upon his arrival, with Manteo interpreting, Amadas made his demand. The records don’t tell us what evidence the Elizabethans had that convinced them that the silver cup was stolen. Could it have been misplaced or lost overboard? It didn’t seem to matter. Despite their objective to win the Algonquians from paganism “with all humanitie,” Amadas and his men exacted their retribution.

The journal from Grenville’s flagship Tiger reported that, “… not receiving (the cup) according to Amadas’s promise, we burnt, and spoyled their corne, and Towne, all the people beeing fledde.” We are left to wonder what Manteo must of thought of the treatment of his fellow countrymen, and if the destruction of the town is why expedition surveyor and artist John White preserved no illustrations of it.

Our analysis of the expedition’s day-to-day journal suggests that Grenville must have waited for Amadas to return from his mission for it still took two days before they all returned to Wococon Inlet. Of course, Grenville would have needed Manteo’s guidance to show them the way during the remainder of their exploration.

White’s “La Virginea Pars” map of the western and southern portions of Pamlico Sound lack the finer detail and more accurate proportions of the shoreline west of Pomeiooc, suggesting either that weather, haste or fatigue prevented the surveyors from taking bearings and making measurements.

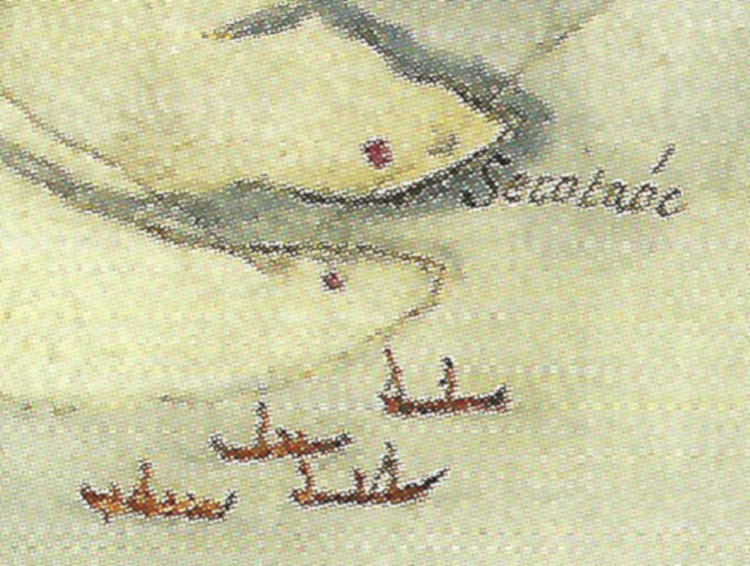

The Bay River, however, is recognizable, and on its north shore is Secotaoc. Secotaoc may have been located on high ground north of today’s Petty Point, although most other writers for unknown reasons are inclined to put it near the swampier Hobucken. Algonquian language expert the Rev. James A. Geary suggested that Secotaoc meant, “they who dwell at the bend of the river,” which would certainly fit this writer’s hypothesis.

Secotaoc and Bay River marked the southern frontier of the Secotan Nation, so the expedition likely overnighted near there that Saturday. From there, their counterclockwise circumnavigation of the sound took them into the waters of the Neusioks, a nation of uncertain linguistic affiliations but possibly Iroquoian, meaning that Manteo’s influence would have had no advantage. The inclusion of the towns Newasiwac and Marasanico on the south shore of the Neuse River was likely the result of White being advised by Manteo of their locations rather than an actual visit.

Likewise, in contrast to his nearly perfect depiction of the Hyde County shoreline, White’s concept of Core Sound and the lower Core Banks does not resemble the geography except in the broadest sense. Of this, Roanoke Voyages historian David Quinn wrote: “White’s coastline for this part of the coast has very little authority as it is very unlikely that he had a chance to survey it even in the most cursory fashion.”

Here we might add that by the time the Elizabethans reached the southern waters of Pamlico Sound they were not only venturing into unfriendly territory but their rigorous tour schedule in mostly open vessels in the heat and squalls of mid-summer must have had them thoroughly exhausted.

The journal for Sunday, July 18: “The 18. we returned from the discovery of Secotan, and the same day came aboord our fleete ryding at Wocokon.” The 43-year-old Grenville, especially, after sleeping rough for seven nights on the water, must have been thrilled to return to his own bed and washbasin in his private cabin high in the aftercastle of the previously damaged Tiger that had been fully repaired.

Three days later, on July 21, Grenville’s fleet weighed anchor at Wococon Inlet and set sail for the north end of Hatteras Island to begin the monthlong process of offloading and establishing Ralph Lane’s colony on Roanoke Island.

Grenville’s exploration of the Native American towns of the Pamlico was over, but ours continues.

There are a few ironies to consider. Even as White the artist and Thomas Harriot the ethnographer preserved for eternity the coastal North Carolina Algonquian people and their culture in pictures and words, the viral diseases brought by the English in 1585, and later by others in the 17th century, eventually led to their near extinction.

It may be no less paradoxical that conservators at the British Museum can tell you more about the paper and pigments used by White to create his “La Virginea Pars” map than most historians and archaeologists know about the locations of the Indian towns depicted on it.

What does it say that Aquascogoc, which was not illustrated by White but instead destroyed by Amadas, is remembered by a historical marker in Belhaven, while Pomeiooc and Secotan, the only two Native American towns in eastern America during the contact period preserved in paintings, have no historical marker near Engelhard or Bath?

At the State Historic Site in Beaufort County, near where Secotan was likely located and where White produced the majority of his illustrations, there is absolutely no interpretation or acknowledgement of it. According to the historic site, Bath’s history did not begin until 1690. Meanwhile, White’s 1585 paintings are displayed at the Jamestown Archaearium in Virginia but not at the place where they were almost certainly created.

Bath is a town of many proud firsts in state history, but it seems to have forgotten its first first. It wasn’t always so.

In 1966, William Shires, a correspondent for the Robesonian newspaper, reported that White’s watercolor map, “La Virginea Pars,” on loan from the British Museum to the State Department of Archives and History, showed Secotan “at approximately the site of Bath, N.C., oldest town in the state.” The revelation inspired the idea of reconstructing the Algonquian town near Bath, similar to Oconaluftee, the popular and economically vital Cherokee village in western North Carolina.

“In a separate drawing,” Shires wrote, “a feature is the central burial house in which White depicted the fallen tribesmen lying in funeral state.” The correspondent was alluding to a painting by White believed to have been made at Secotan depicting the Algonquians almost Egyptian-like veneration of the bones of their dead werowances, or kings.

More than a century earlier, in fact, Bath residents recognized that the eroding shores of their creek were gradually exposing the mortal remains of a long-lost world. In 1857, Joseph Bonner wrote a letter to a friend stating: “Many relics of Indians have been discovered in this place and vicinity at four different localities on the bank of the Creek and within the limits of Town, where excavations have been made, immense quantities of Indian bones and other remains have been found. Indeed the whole bank would seem to be a cemetery.”

Thus, the bones of the kings of Secotan and their people have long since washed away or been plowed under, perhaps under the very corn field that once fed their town and the Elizabethans who visited them 435 years ago.

According to the Robesonian, when state and county leaders in 1966, along with the chairman of the history department at the then East Carolina Teachers College, considered the economic opportunities of reconstructing Secotan, the Historic Bath Commission led by Edmund Harding of Washington gave the project the highest priority. But nothing ever happened and Secotan was soon forgotten again.

From time to time, archaeologists have shown some interest in the locations of the Pamlico towns of the Algonquians. In a 1956 report of his survey of cultural sites in the Outer Banks region, Louisiana State University’s William Haag described an extensive midden on a 15-foot-high bluff along the west bank of Bath Creek. Hundreds of feet inland, shell fragments and potsherds were also found.

Four years later, archaeology pioneer Stanley South made the first of two visits to the west bank of Bath Creek. At the time, someone diverted South’s attention from Native American artifacts to investigating evidence of the pirate Blackbeard’s connection to Bath, possibly hoping to find buried treasure at Plum Point. South left empty-handed.

Other searchers, less professionally qualified but with more curiosity, have had better success.

For many years, a farmer named Warren Harris cultivated the fields along Bath Creek and turned up vast numbers of Native American artifacts. He located a chipping station where stone implements were produced and oyster shell middens.

Fishermen and family boaters with young aspiring “Indiana Joneses” have also frequently recovered prehistoric artifacts from the shallow waters off the creek’s west bank, including large fragments of fabric-impressed ceramic jars.

In 1980, East Carolina University archaeologist David Phelps showed up for a time and recovered numerous samples of precontact period Colington phase ceramics — pottery typically fabric impressed, simple stamped or plain — but that was the extent of his survey.

In the mid-1980s a more extensive, two-phase archaeological survey was conducted at the site on Bath Creek in advance of an extensive bulkhead to be built along the shoreline.

The Delaware firm contracted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to perform the survey reported that a Late Woodland, or A.D. 800 to 1600, village had been established there and maintained for many years.

“The large area of artifact distribution, high frequency of subsurface features, high percentage of Colington and Cashie wares, and the indication of multiple intrasite processes suggest (a) substantial village. The presence of at least three partially reconstructible ceramic vessels of Colington ware in a single feature (Feature 31) attest to a semi-sedentary occupation. … Synthesized, this data can be interpreted to suggest that the site was inhabited for an extended period of time, either as a multi-seasonal or a permanent settlement.”

A historian with the Department of Cultural Resources wrote the following supporting statement in a 1987 report titled, “A Brief History of the Bath Creek Site:”

“Archaeologists have recently concluded that an undeveloped tract of land on the west side of Bath Creek in Beaufort County may hold a rich potential for more thorough investigations in the future. The presence of ceramic fragments, projectile points, and other artifacts of the late Woodland period indicate that a major Algonquian Indian village may long have existed on the land … There is further possibility that it was one of the several villages visited by the Roanoke colonists and depicted in the drawings of John White.”

The Delaware archaeologists cautioned that the culturally significant prehistoric and historic components of the site could be adversely impacted by the bulkhead project and urged that the site be nominated for placement on the National Register of Historic Places. The bulkhead was built anyway and an early 18th century brick structure was destroyed in the process. The site, arguably one of the most historically important properties in North Carolina, was never nominated. Soon after, interest in it eroded away.

In 2010, the Economic Development Commission of Beaufort County attempted to reinvigorate interest in the Native American town as a way to boost the county’s sagging economic outlook. In a letter from the First Colony Foundation to the Beaufort County EDC executive director, an archaeologist wrote: “This section of land on the western side of Bath Creek is considered by many as the most likely location of the village of Secotan. … Over the years, archaeologists from Haag to Phelps have eliminated most other locations along the northern and southern banks of the Pamlico and its tributaries.”

For a brief time, it looked promising that Secotan might finally be investigated. However, while there was enthusiasm among some people for restarting archaeological work on the west bank of Bath Creek, substantial resistance from other powerful groups led to an abrupt shutdown of the initiative. Secotan, today, remains a cornfield.

As for the only other town painted by John White, North Carolina’s 400th Anniversary between 1984 and 1987 celebrating the Roanoke Voyages sparked a conscientious archaeological effort to find Pomeiooc’s location in Hyde County.

Site tests and excavations by ECU archaeologists at a previously identified cultural site in a field near U.S. 264 in 1985 and 1987 found post holes and artifacts indicating a small, palisaded Native American farmstead dating to the mid-1600s. The site was determined to have been occupied by Machepungo or Mattamuskeet Indians, possible descendants of the Carolina Algonquians.

The report concluded that evidence of the walled town’s location may yet be found in an unexamined forested section of the ridge surrounding Lake Mattamuskeet near where White’s map indicated it would be. But to date, no other efforts to locate Pomeiooc are known to have been made.

In a 2011 publication titled, “The Archaeology of North Carolina: Three Archaeological Symposia,” archaeologist David Phelps was quoted as stating in 1983 “‘somewhat plaintively that, (the) North Carolina Coastal Plain has been the least known archaeological region of the state, received less professional attention, and had until recently witnessed fewer archaeological projects’ than either the Piedmont or Appalachian physiographic region.”

The archaeologists contributing to the publication admitted that not one of the 27 Algonquian villages either painted by White or described by Harriot, most near Albemarle Sound or Chowan River, had been “definitively relocated and investigated archaeologically, though several have been postulated as being contemporary with villages depicted on the 1585 John White map.”

Over the years it seems nearly all of the coastal archaeological efforts, resources, state and private funding and media attention have been directed at finding the “Lost Colony,” which was never painted by John White and likely will never be definitively found, at the detriment of locating evidence of Secotan and Pomeiooc, no less significant sites so masterfully illustrated by the artist. It may even be possible that Aquascogoc could someday be found near Pantego.

What is needed is commitment and courage on the part of the state’s archaeologists to search for these historic and prehistoric North Carolina towns before their locations are inevitably destroyed by development. Not doing so may be as injurious to the Pamlico Algonquians as Amadas’ unfortunate torching of Aquascogoc, or their near extinction caused by European viruses.

Just as the Algonquian towns of Pamlico Sound were unknown lands at the start of Grenville’s circumnavigation in 1585, in some ways, 435 years later, they remain “terra incognita.”